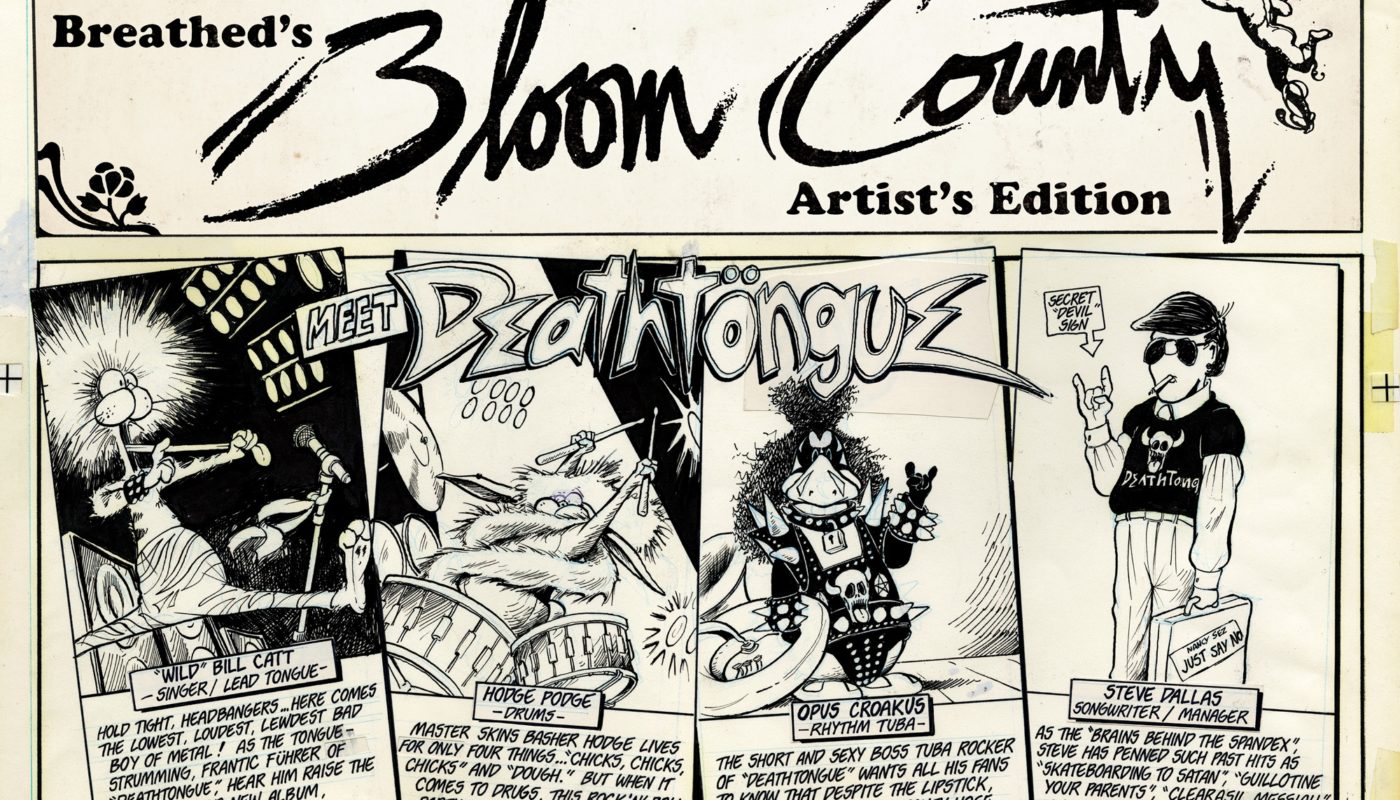

BERKELEY BREATHED: Bloom County launches December 8, 1980

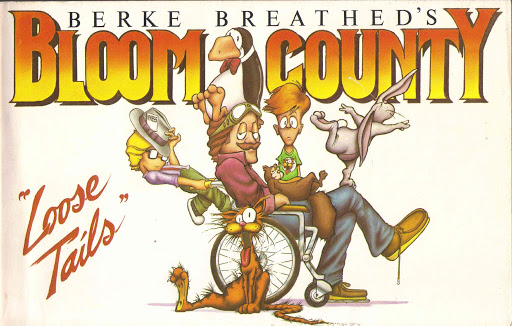

Berkeley Breathed’s comic strip Bloom County has been around for seven years when Breathed won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning. The uproar in the cartoonist world was deafening. The first wave of insults was based on the fact that Bloom County wasn’t actually an editorial cartoon (generally single-panel cartoons around a current event, and without any running narrative). But follow-up criticism was much sharper, and much angrier. The charges leveled against Berke Breathed was that he was unoriginal. That Bloom County was, at best, a collection of other people’s ideas, re-packaged in a giant merchandising scheme designed to sell Opus the Penguin telephones and Bill The Cat t-shirts. That Breathed reacted to this criticism with a prickly condescension did not help matters. And as merchandising and awards piled up, and as criticism piled on Breathed retired the strip and moved on to his next comic strip, Outland. In the collection of the final years of Bloom County, Breathed was unable to find another cartoonist willing to write the book’s foreword, so he wrote it himself. “It’s not that it wouldn’t make me feel all warm inside to have a pleasant testimonial from any of my colleagues; it’s just that I can’t think of anyone who would care to write one.”

The argument against Breathed was that he wasn’t a comic creator; he was a thief.

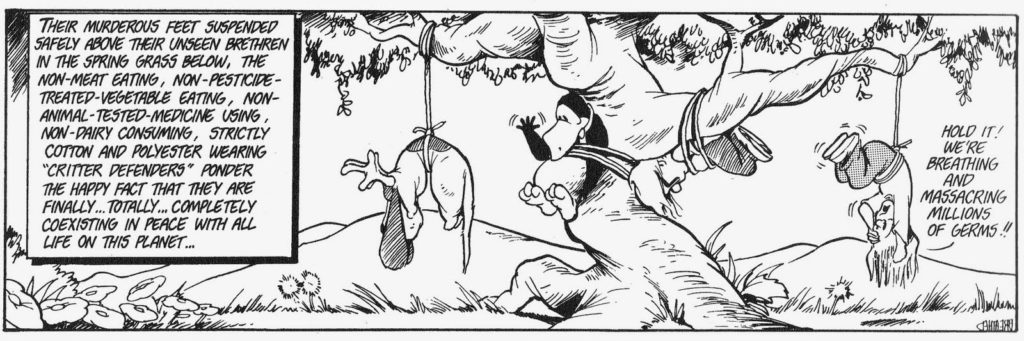

Breathed openly admitted to not growing up as a fan of comic strips, a fact which (when coupled with the “thief” argument) made his ascension within the comic strip universe seem more openly calculating. The critical dissection of Bloom County was an attempt to catalog the sources of nearly every element of the strip. Bloom County had archetypal political talking heads and overly-cartoonish political antagonists, like Doonesbury. It had talking animals who led political discussions, like Pogo. Breathed would run weekly theme strips, a technique created and developed by Charles Schulz for Peanuts. Breathed, however, would run weekly themes that Schulz had already done, like a week of characters lying on a hillside and finding shapes in the clouds. To Breathed, all of this was homage. To the other comic strip creators, it was theft. In truth, it was pastiche.

Pastiche is a literary technique – also used in visual art and cinema and theater and dance, etc. – where a creator liberally borrows from another work to bring the emotions associated with the initial work into the new work. Filmmakers are famous for this; Quentin Tarantino is probably the greatest film pastiche artist of all time. When he puts Beatrix, the heroine of the “Kill Bill” films into a yellow jumpsuit, he indirectly references both Bruce Lee’s “Game Of Death”, a film in which the main character survives an assassination attempt and has to kill off his assassins, one by one. Beatrix’s suit also references Steve McQueen’s firesuit in the 1971 movie Le Mans, about the 24-hour race. Despite being a box office flop, images of McQueen in the LeMans jacket are well-known to movie buffs, and bring with them emotions of grueling effort, danger, exotic foreign activity, and a deep cool in the face of possible death. That’s pastiche. Tarantino builds the characters in all of his films on a foundation of cinematic influences that came before him. Comic strips artists and cartoonists do the same thing, and yet few have met with such vitriol from the industry as Berke Breathed.

The irony behind that is that as the cartoon industry grew less and less respectful of Bloom County , its popularity with the general public continued to grow. When Breathed retired the strip in 1989, the general public was distraught at what it would lose. As readers/viewers/fans, we love pastiche. Uncluttered by a deep knowledge of influences, comic strips like Bloom County were loaded with familiar references that people found comfortable and familiar and engaging, probably without recognizing that their comfort was based on having seen similar elements in Peanuts cartoons or Doonesbury cartoons.Pastiche, when unnoticed, is a familiar and warm presence. When noticed, it is generally a welcome presence which kick-starts an “I see what you did there” revelation. It’s only in certain circumstances that pastiche is treated with the kind of anger Berkeley Breathed could elicit.

Part of this comes from our willingness to admit to influence, and part of it has to do with how openly we embrace and admit to influence. Years ago, I went to a gallery showing of the work of cartoonist Jerry Scott. In one of the panels of his cartoon Zits, he had drawn the main character Jeremy in an excited state, with his mouth off-kilter and in the shape of a perfect triangle. In non-reproducible blue pencil, he had drawn an arrow pointing to the mouth directly on the art with the comment “Calvin’s mouth!”. And so it was. To show joy and excitement, he had referenced a trick from Bill Watterston’s Calvin & Hobbes. I would steal that trick when drawing, as well. Jerry Scott’s pastiche was a celebration of Watterston’s technique, down to the open admission written right on the bristol board itself. Breathed offered no such admission, which is as much his fault as our society’s. Academia in this country is founded on the idea of identifying and cataloging influences, but as a society, we fall in love with the people who seem to create from an otherworldly fabric. Shakespeare. James Joyce. Picasso. Einstein. Steve Jobs. We think of them as being almost mystical in their creations, but their influences are known, albeit more difficult to identify.

No person exists without influence. Every word we know was learned from another person, either live or reproduced in books or recorded words. There are arguments that some facial expressions and physical motions are unique and inborn to all humans, but beyond that, everything that makes us individuals is nothing but a collection of learned influences from a million different sources. The fact that documenting the sources of our influences is a near-impossible task doesn’t make that source any less real. We are all merely products of what we have been exposed to, and of what we have chosen to be influenced by. Berke Breathed and Bloom County were no different.

I laugh like my father.

I conclude my letters like Neal Cassady.

I sing using a breath pattern I learned from watching a Joe Cocker performance.

When I used to smoke, I lit my cigarettes like Stevie Ray Vaughan.

When I read Shakespeare, I hear it in Orson Welles’ voice.

At bars, I carry myself like a bouncer I once met at a strip club.

I have a certain one-liner I use that I learned from an episode of The Rockford Files.

My childhood made me afraid of conflict, so I tend to write in the passive voice.

The decision we all must face at some point is to what extent we celebrate our influences. The idea of pastiche is that it is directly lifting a recognizable element from another work and putting it into our own. But with enough effort and time, we could probably identify most of the influences of every element of our lives, down to the very word. Some of those elements would be from people we love, some from people we hate. Some of the elements would be the influence of people we respect, and others, from people we don’t. But the dissection of that – the digging into our influences – shouldn’t be perceived as a degradation of “self”. The fact that we are a collection of our influences -and the fact that some of our influences are people we despise – doesn’t make us less human. We’re as human as the next person (who is also a collection of influences). What makes us unique is what influences we have allowed into our lives, and to what depth. What can make us fulfilled and relatable is an awareness of those influences, and an open gratitude to their role in making each of us unique.