FRANK MILLER: born January 27, 1957

I was recently talking with an acquaintance about a crime that had been committed. His reaction to the crime was severe and punitive. He talked of justice, but his language was vengeance. I couldn’t bring myself to feel that way, and it seemed to upset him. “What if that had happened to one of your kids? Or your wife? What then?” I explained that I believe in the idea of a justice system, and I would want them to handle it. Furthermore, there is a reason I – or anyone I knew – would not be allowed to sit on that jury. Because angry people are irrational. They want vengeance. They don’t give a damn about the law or the courts or justice. They want blood, and so we make sure people who might be affected don’t sit on juries. Angry people are irrational, I explained, and irrational people make terrible decisions. I’ve long believed to be careful around anyone trying to make me feel angry about an issue. Anyone recruiting angry people is not to be trusted; if your case only works for irrational people, you probably need a better argument. (I’m looking at you, political talk shows…) The world is filled with things that need to be condemned and require a stance be taken against them, but we need to learn when we’ve crossed the line from “part of the solution” and become “part of the problem”.

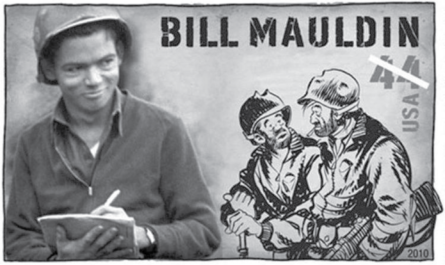

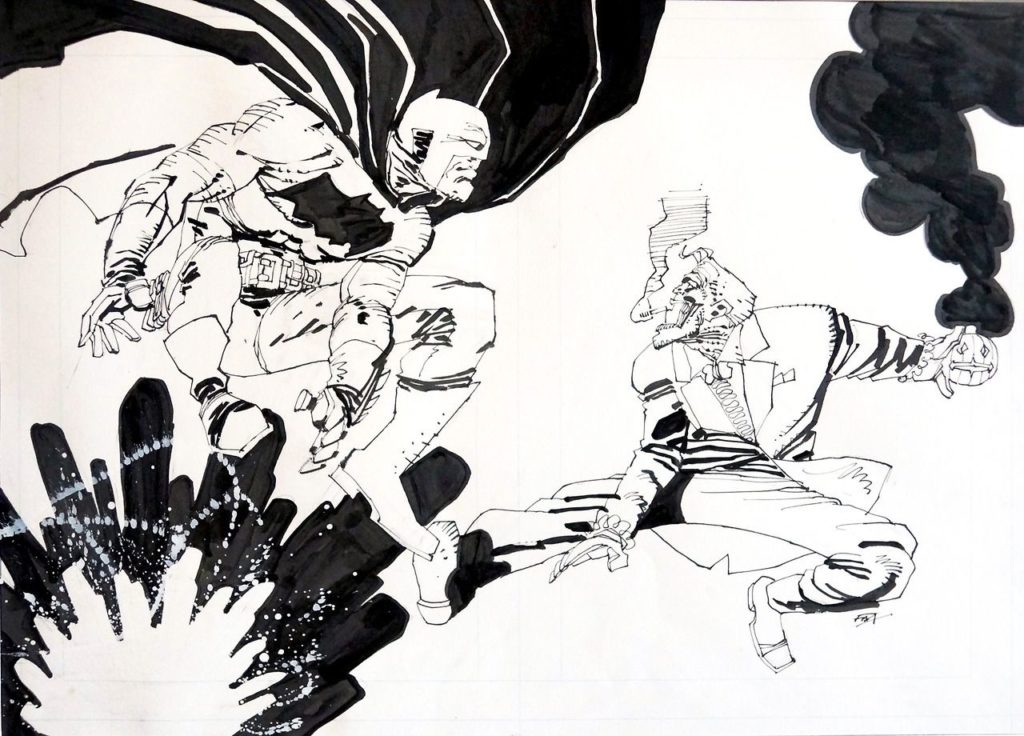

Frank Miller was always a comic writer in danger of falling over that line. Miller had been drawing and writing for years when his big breakthrough occurred with 1986’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. In the series, Miller extricates Batman from the camp of the 60s TV show and the comics’ version of Batman with a spotless moral code and “Gotham citizens, first and foremost” attitude. Instead, Miller wrote Bruce Wayne/Batman with a massive dose of reality. In the series, Batman was now 55 years old and coming out of retirement to fight in a world that had grown increasingly chaotic and criminal. Batman was violent and brutal and fairly misanthropic. The Dark Knight was an over-reaction to fear, and had no interest in partners or adulation or friendships. Miller finished the 80s with a series called Batman: Year One in which he altered the Batman origin story to make the Batman of The Dark Knight Returns make more sense. He made the young Bruce Wayne a traumatized child, consumed with fear that stemmed from the unforeseeable murder of his parents. In Miller’s universe, Batman seemed to fight criminals so they could never hurt him, not to save Gotham City out of a sense of civic pride. It was an easy concept for Miller to voice; he’d been in New York a number of years and had suffered muggings and assaults and home invasions. He began to channel the rage and frustration he felt from being a victim into the work, and the world responded.

When the 90s began, Miller launched the title Sin City. Stylistically, critics would refer to is as “noir”, characters and visuals that were steeped in shadow. But unlike classic noir films, Sin City was literally black and white. Miller’s characters existed in negative space, literally and emotionally. Sin City is a world of monsters and victims. Looking at Miller’s work chronologically, it was the direction he was going. Unlike most superhero comics, which live with a subtext that questions why a superhero even cares about the society he/she is trying to save, Miller tacked an addendum onto the question: “…and what does that do to a superhero?” With each issue of Sin City, the “good guys” were killed off doing noble battle with monsters, and replaced with… monsters. The appearance of Marv, a 7’ tall psychopathic murderer became one of the most compassionate characters in the series. When Marv wanted to do a good deed, he ran through the city killing thug after thug with a reckless glee. When Miller killed off the few remaining “good guys” in all of Sin City, he replaced him with the spirit of vengeance. Miller’s world was slowly morphing into a world of monsters and prey. Bad monsters fed on prey; good monsters fed on bad monsters. All in a beautiful, stylized package. The problem? It was beginning to feel too cartoonish, too unrelateable. In 2001, Miller began work on the next Batman series, moved back to New York, and found a place in Hell’s Kitchen. He continued to create a world where monsters battle monsters until September 11, when the World Trade Center was destroyed a few blocks from his home.

It was around that time that Miller seemed to come unhinged. His work became increasingly more isolated, his heroes and his villains more monstrous. A strange nationalism began to creep into his work, given Miller’s previous statements on the meaninglessness of patriotism. He released The Dark Knight Strikes Again, in which Batman once again comes out retirement. But now he gathers an army of misfits and monsters and malcontents to battle the evils of the world; once again, monsters versus monsters. The series was critically and commercially panned. Miller took to his blog to condemn anyone not entirely terrified of Islam. He took umbrage with the Occupy Wall Street movement. He embraced the camp of the Batman he tried to update and began work on a Batman vs. Bin Laden book called Holy Terror, Batman! He embraced propaganda as a tool for fighting “Islamists” and “traitors”. He divorced his wife. He posted lengthy reactionary screeds online. He met a new girlfriend, and together they (allegedly) terrorized an assistant in a fashion straight out of the tabloids. By the end of the decade, by all accounts Miller appeared to be… a monster.

Nietzsche wrote, “Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster… for when you gaze long into the abyss. The abyss gazes also into you.” The sad part about Frank Miller’s meltdown is that it was unnecessary. Monsters do exist in this world. And they need to be fought. But monsters in real life are like the monsters in literature – rare and destructive. But Miller grew angry, and that anger made him irrational. By focusing only on the monsters, Miller’s worldview became Sin City. He saw the world in a similar black and white. But we owe ourselves more than that. We owe each other more than that. When Miller had his first major success, it was because he understood that human being exist in the nuances; we are all shades of grey. And as his anger grew and his irrationality bled away, his art and his beliefs morphed away from that nuance. Miller’s characters turned into monsters, and Miller himself turned his back on his humanity. And he turned his back on the world with no end game in sight. Because if we become monsters to battle monsters, it’s frightening enough to lose that fight. But what if we win? The world is safe, and turns to find the only monster remaining… us.