THE ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME: First class inducted, January 23, 1986

When the first class of “early influencers” was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, many of my friends were appalled. Never mind that the Hall of Fame was, at that time, more concept than reality; it would be almost eight years before the actual building was constructed and opened to the public. Never mind that the Hall of Fame board of directors hadn’t even settled on a location for the Hall of Fame, or even a clear mission. My friends and I are classic Generation X-ers, the kind who find meaning and guidance in music. For many of us, music wasn’t just a soundtrack to our lives, it provided meaning and spiritual guidance. Rock & roll was a supplemental – sometimes a surrogate – parent for us, and we tended to that relationship accordingly. We obsessed over minor details. We made lists and compared and categorized and traced influences. Music represented our moods and our moments and our development through adolescence. Rock & roll was as broad as the human experience: it could be gritty or polished, it could be loud or quiet, fast or slow. The rules that governed rock & roll were as loosely-defined as the rules the governed adolescence, and my friends and I used the template of rock to try to understand life. If we could decode and understand rock music, the world would fall into place. As a result, the idea of a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame felt like a betrayal. To many of my friends, enshrining an art form created to be wild and unruly didn’t feel like putting a wild tiger into a cage, it felt more like encasing the tiger in Lucite.

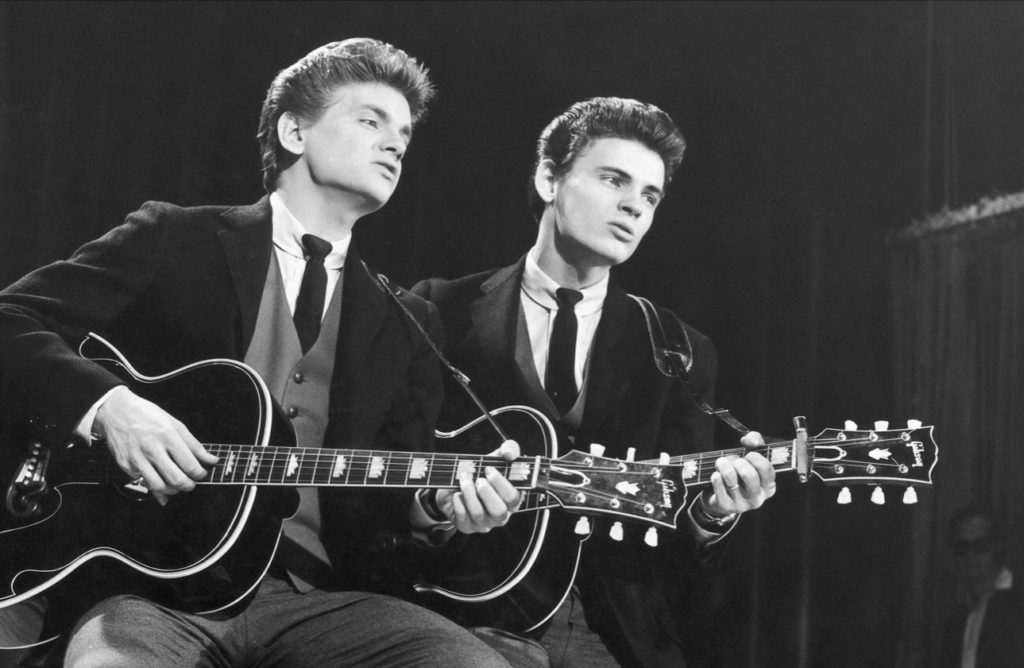

What was interesting about the inaugural class of inductees to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame was the obvious care that went into selecting them. The selection committee obviously understood the importance of honoring the broad cross-section of rock & roll pioneers, whether they were rock musicians or not. The class included icons (Elvis, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino), non-rock influences (Robert Johnson, Jimmy Yancey, Ray Charles), soul (Sam Cooke, James Brown). They included the smooth harmonies and clean vocals of The Everly Brothers as well as the apeshit energy of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. It was a great testament to the indefinable nature of rock & roll, and its roots as a mash-up of styles. Was rock & roll an offshoot of country? Or gospel? Or the blues? In a word, yes – to all three. But what made rock & roll so great was that it was influenced by everything, but not beholden to any of them.

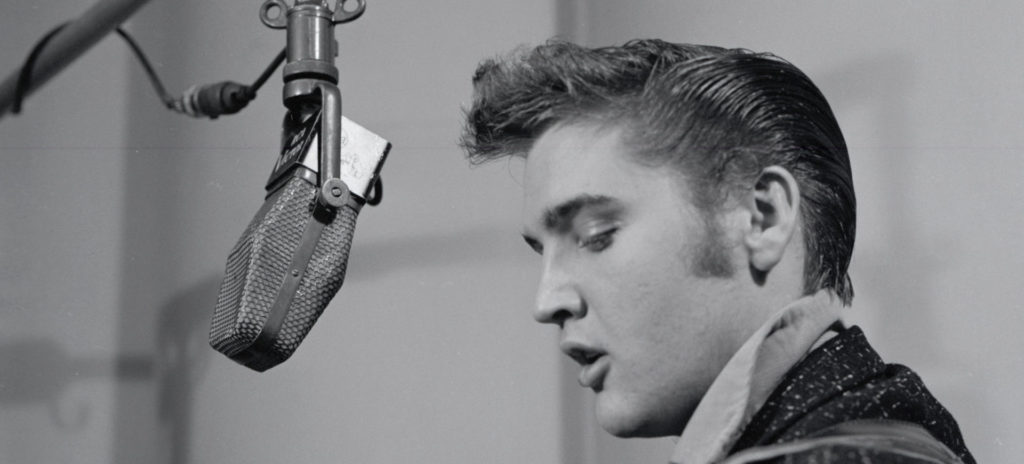

When Elvis Presley was called to Sun Records in 1954 to record for Sam Phillips, he sang Arthur Crudup’s blues song “That’s All Right”. And he kept the blues structure, but his voice swung between gospel and blues phrasings. What Elvis didn’t do was bring a studied sense of genre to the piece; primarily because he couldn’t. Elvis had no formal voice training. Even he recognized that his voice didn’t fit within any prescribed genre; “I don’t sound like anyone” was how he had described himself to Phillips’ secretary earlier in the year. He didn’t understand music theory enough (or have a good enough ear) to know how to harmonize; a week before the audition, he had failed an audition for a local vocal quartet because “he couldn’t sing”. Elvis was all influence with no training, and as such, he was rock & roll’s first true icon. Unlike skilled and knowledgeable musicians like Chuck Berry and Ray Charles, Elvis provided the roots of rock & roll: populism.

What makes rock & roll such an important force in our lives is its accessibility. It’s not an art form that requires years of study. It’s not an art form constrained by specific chord structures (like the 12-bar blues) or song structures (like pretty much all country songs). It’s not even an art form that demands technical perfection or rigorous adherence to arrangement. From its earliest examples, rock & roll was more interested in exposing the artists feelings as they recorded than in using the acculturated notes and chords and tempos to represent that emotion. Minor chords may have shown heartbreak in early country records, but rock & roll was more interested in hearing the catch in the singer’s throat or an angry, overly-aggressive chord from the guitarist. Formal training was not required; honest emotion was. By the time punk music rolled around in the 1970s, even knowing how to play your instruments became optional. Rock & roll was music for everyone. If you had feelings and weren’t afraid to convey them, you could turn it into rock & roll music, and you could pull influences from anywhere. My wife once told me that after a mistake during band practice, her guitarist told her, “It’s rock & roll. It’s not supposed to be perfect.” That’s the perfect language to describe rock & roll. It doesn’t “allow” mistakes or “forgive” mistakes; it’s ”supposed” to have mistakes. Mistakes are proof of humanity and vulnerability and forgetfulness and over-reaching. Mistakes are part of our humanity, and so they’re a part of rock & roll.

Nearly twenty years after the inaugural class of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame was selected, I must admit that I have been to the Hall of Fame. And despite how some of my friends feel about it, I enjoyed it. Because we live in an age where it’s growing increasingly more difficult to find true rock & roll, in both design and in spirit. Music has become fractured and specialized and categorized and so specifically market-driven that it’s rare to find an artist I can genuinely call a “rock act”. In today’s market, rock & roll is more of an influence than an end state. Country artists all have strong rock influences. Blues artists have rock influences. But there are fewer and fewer rock acts out there. As a guy who spent his youth cataloguing and analyzing rock & roll and mining every element of it for meaning, the loss of rock & roll is more than a mere shift in the marketplace. Somewhere inside of me, the loss of rock & roll feels personal. It’s something I feel on a personal level, and something I feel like I’ve experienced. As I’ve grown older and my thoughts and feelings and directions have become fractured to accommodate the needs of others and the things I share have become increasingly edited for public consumption. The purpose of rock & roll was open, unrestrained communication. As it matured, the message became increasingly compromised. It’s a scenario many of us face as we progress into adulthood. And when I look at my life, and the life of other adults I know, and when I look at the current musical landscape, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame no longer feels like encasing a tiger in Lucite. It no longer feels like a zoo. It feels like a preserve. An important space to remind us that the best parts of us live beyond marketplaces and audience segments. That the best parts of us live beyond compromised messages and a search for a flawlessly-delivered message bland enough to reach far and wide. The best parts of us live in the moment, in the message that demands to be outside of us, no matter how ugly it comes out.

The best parts of us are like rock & roll, and both deserve to be preserved.