THE CROW: Issue 1 released February 1, 1989

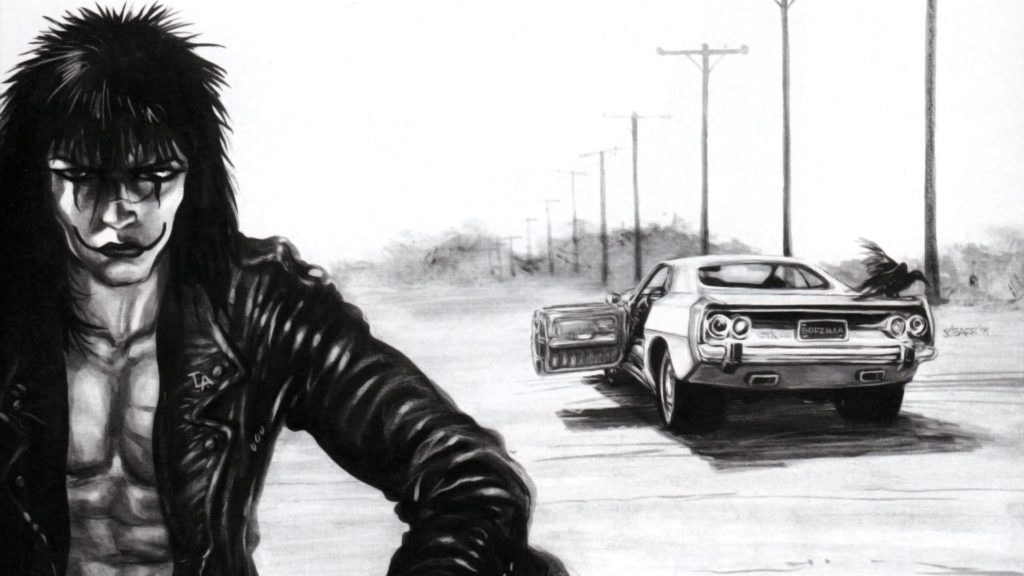

I met The Crow writer-artist J. O’Barr at a comic convention in Chicago in the late 90s. The movie version of The Crow had been released a few years earlier to moderate acclaim, which was overshadowed by the on-set death of the film’s star, Brandon Lee. When I saw O’Barr, I was blown away by two things: that J. O’Barr was there in person, and that nobody was at his booth. My best friend had turned me onto The Crow right after issue 2 had been released. It was early 1990 and I was into Iggy Pop and Joy Division and Rimbaud and Baudelaire, all of whom O’Barr referenced in the first issue. My friend was sure I would love it, and I did. Meeting J. O’Barr a decade later was a bit of a shock. I had so closely identified the creator with the character, I assumed O’Barr would be equally as tortured as the people we both admired. What I didn’t expect was a guy so familiar. He was really quiet, hunched over the pictures he was drawing of Eric, The Crow’s hero and avenging angel. The man running the table and handling the merchandise sales did most of the talking for the two of them. I tried to engage O’Barr with talk of French Symbolist poets, and how they’re disaffection with life, while not actual grief or grieving, was like the perfect soundtrack to grief. He acknowledged me as he drew, tossing in a few comments here and there. He seemed shy and introverted, like the process of talking to fans wasn’t unwelcome, but certainly drained him of energy. I imagined he would be like Ian Curtis; in reality, he was more like… me. I ended the conversation a few times, but each time I would go to leave, O’Barr would drop another one- or two-word comment and extend my “visit”. Finally, he finished the picture he was working on, and he asked me if I wanted it. I did. We continued talking for a little while, and a few other fans finally approached the table and I walked away, more intrigued than anything.

Years later, a friend’s wife loaned me a DVD with an interview with J. O’Barr on it. On it, O’Barr described the genesis of The Crow. As a high school senior his fiancee/high school sweetheart was killed by a drunk driver. Grieving, O’Barr joined the Marines and was stationed in Berlin, where he illustrated combat manuals. In his spare time, he began to write and draw The Crow. For O’Barr, the process was meant to be cathartic – a way to get over his grief. It was an idea that I understood. In an unfortunate coincidence, my best friend who introduced me to The Crow in 1990 would die a couple of years after that due to the incompetence of a doctor. I understood the passion thyat drove O’Barr. One of the worst aspects of grief is the feeling of helplessness. Knowing that you couldn’t have saved the person’s life, it is easy to slip into flights of fantasy about what remains: getting even. Unable to bring people back, we can focus on ways to exact justice. I know I had dark fantasies about the doctor who misdiagnosed my best friend. It was – for a time – the only way it felt that the world could achieve balance again. O’Barr experienced the same innate, unquenchable need for justice and he created a world on the page to experience that. In his book, an avenging angel returned from the dead to systematically destroy everyone responsible for the death of his one true love.

From the simple perspective of “helping a man grieve”, The Crow was a reasonable exercise. Grief is a series of conflicting emotions that seem to attack in cycles: initially small cycles, but as time goes on, the cycle’s circumference grows larger and more diffused. Pain never goes away, it just arrives less often and with decreasing severity. But in the early years of grief, feelings hit like a tidal wave. One’s day’s vengeance fantasies become the next day’s survivor’s guilt, which becomes the next day’s gratitude. Grief is many, many emotions. The Crow was a great tool for dealing with the vengeance fantasies, for soothing the part of the loss that kicked against the injustice of fate. But in an interview given to market the film version of The Crow, O’Barr admitted that the catharsis he sought was never delivered. In fact, he claimed the creation of the book only made him more self-destructive and angry. Which, in hindsight, makes sense.

Grief is a process of numerous, conflicting emotions. But so is being in love. So is heartbreak. So is passion. Many of the stages or processes we experience in life consist of numerous emotions which oftentimes oppose each other. When we choose to ignore some emotions in favor of others, we rob ourselves of the entirety of the process. By focusing on the need for vengeance J. O’Barr felt (much less by feeding it regularly and vividly), he denied other parts of the grieving process. He denied the joy of good memories. He denied the gratitude for the moments he had. He denied the sadness he felt. And the moments he missed out on when he could have been weeping and recovering and experiencing the entire relationship in a balanced way, he filled the time with rage.

As guilty and as lost as I was with the death of my best friend, I was lucky enough to be able to remember the good times. I was lucky enough to be able to feel gratitude. It was the balance created by so many conflicting emotions that kept me sane enough to continue on with life, knowing that as off-kilter as I felt in any moment, I would feel balanced soon enough, and then off-kilter in a different direction soon after that. But that’s the nature of complex emotions. But how often do I – or any of us – lose that ability in life? How often do we unintentionally damage a relationship by fixating on a single element or emotion? (Or simply deny a few important emotions?) How often do we stunt our emotional growth by fixating on a painful moment in our past, and allow the fear of that moment to corrupt who we are? How frequently does the easiest path in life equal an avoidance of the very emotions we need to reconcile? How many of us go through our daily lives with only a partial view of the world, limited by our own insufficiencies and weaknesses, and wonder why things don’t get better? I can personally attest that I’ve done it most of my life.

If we, as humans, are what we focus on, then I must admit that I am – on my best days – only a partial example of the world in which I live. And not a only the best parts, either. Of the challenges that lie before me, becoming more fully integrated is a key factor: to feel what needs to be felt, to give attention to the things that demand attention, and to deal with things I don’t want to deal with. In J. O’Barr’s The Crow, the hero Eric returned from death to kill everyone who had killed him and – more importantly – his beloved fiancee, Shelly. One by one, he rid the world of the monsters, and then he returned to death, where Shelly awaited him. Eric is a great one-dimensional literary character. But life is not one-dimensional. All of us would stand to carry a little Eric within us. But only a little. We need to make room for many, many others.