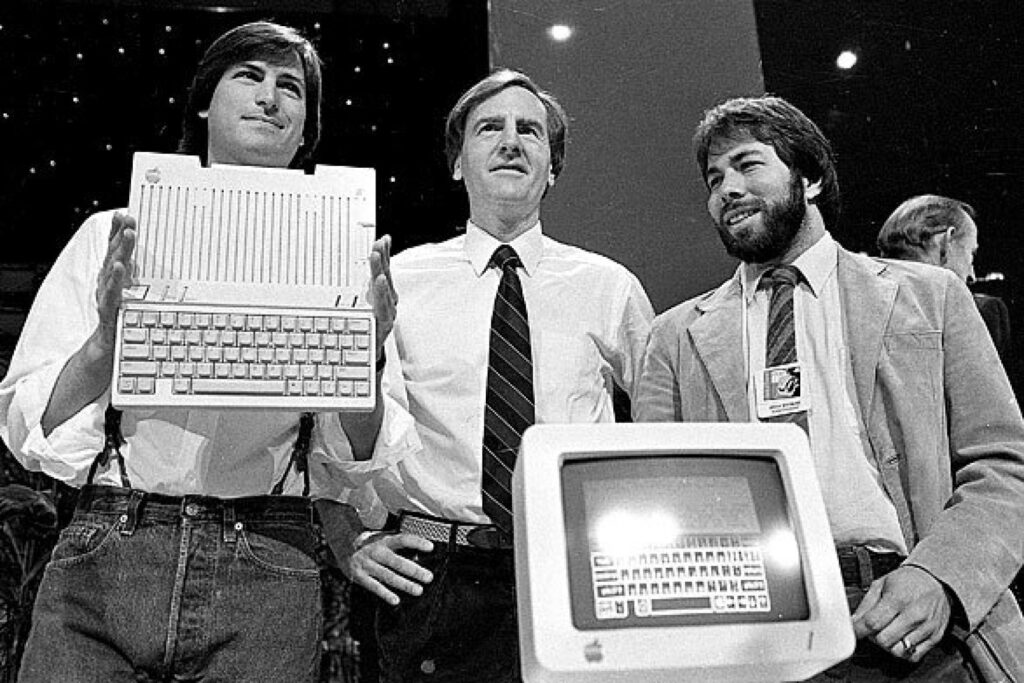

APPLE, INC.: Incorporated January 3, 1977

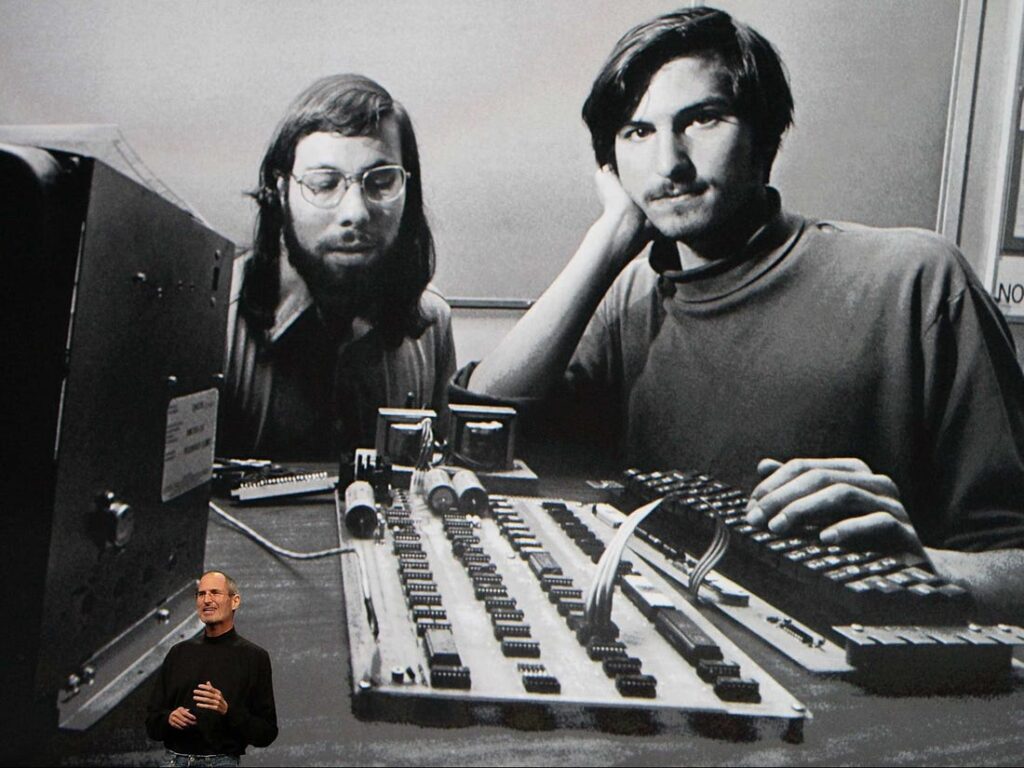

A co-worker recently posted a GIF to LinkedIn that (basically) said, “The Product Development team can stop asking ‘When are the sales teams going to SELL some of what we’ve built?’ as soon as the sales team can tell the customer WHY it was built, not WHAT it is.” It’s a common perception in business; “if we build something amazing, they will buy it.” I’ve seen it time and again. And generally, what I’ve seen built was amazing. But I’ve also seen dozens of these amazing products sit unused until they wither and die. In general, these products are not designed or built in a vacuum. At some point, some piece of data or some opinion led the company to believe that the product was necessary, which led to its creation. Yet, somehow, it still failed to connect with an audience. So many products are built by committee, with incomplete ideas about how they should work and what they should provide that they fail to register with actual people. Other products, on the other hand, immediately connect with audiences. Confusing the matter even more are the products which connect with an audience who didn’t even know they needed it or wanted it. When Steve Jobs died in 2011, his record at Apple (never mind his equally-impressive record at Pixar) was possibly the highest level of achievement in product design. Jobs regularly provided the consumer with things they never imagined, yet immediately felt they couldn’t live without.

What is about Steve Jobs’ process that made him so successful at product design? Having read Walter Isaacson’s comprehensive biography Steve Jobs, it was apparent that part of what made Jobs so effective, quite frankly, ran concurrent with a fairly terrible personality. At one point in the book, Isaacson quotes on-again/off-again girlfriend Tina Redse, a therapist, who suggests that Jobs may have had an undiagnosed personality disorder. Regardless, something in Jobs kept him pushing and demanding for what he wanted without consideration for the feelings or emotional needs of others. Similarly, his abilities to manage people were far from optimal coaching techniques. Jobs seemed to be more prone to manipulation, tantrums, and bullying than positive coaching. He could be inspiring, certainly. But for the people who ran afoul of his vision, he could be even more crushing.

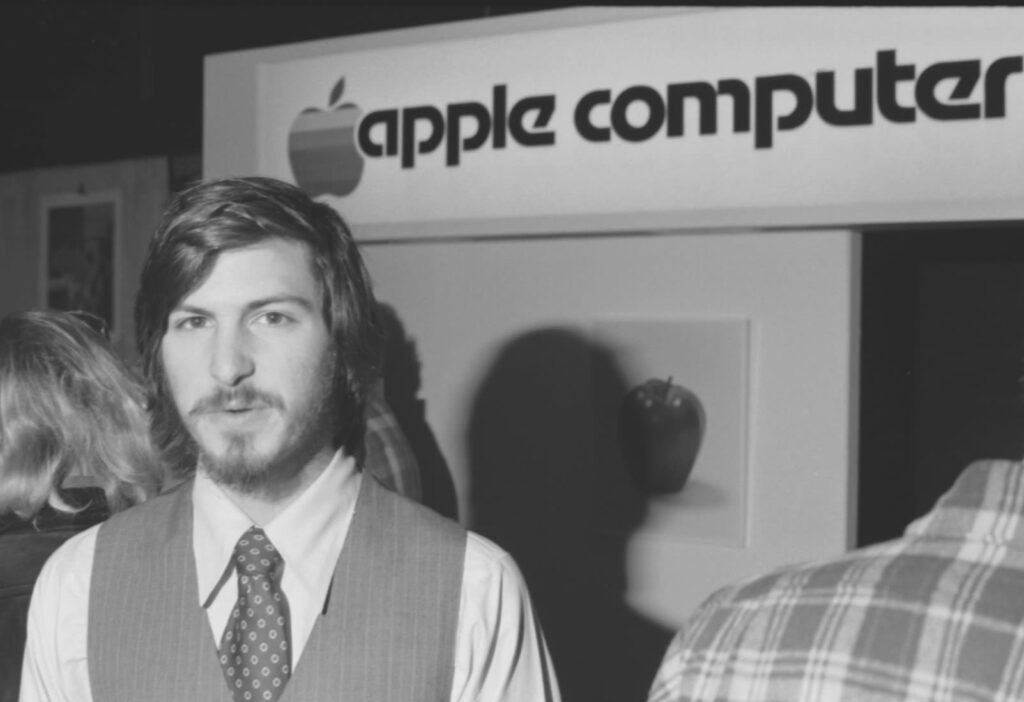

Still, there’s something undeniably appealing in that narrative. It’s like something out of Ayn Rand; the solitary man, obsessed with his vision, committing everything to see it completed. Trampling friendships. Disregarding common courtesy. Forgoing protocol or social convention (one story in the book told of middle school-aged Steve Jobs needing parts to build his own frequency counter, and repeatedly calling Bill Hewlett, the founder of Hewlett-Packard, until Hewlett relented to speak with him and sent him the parts, free of charge). It’s an appealing story to a society borne of the Puritan work ethic. The weakness in the story is not in the “how”; Isaacson alone has detailed exactly how Jobs steamrolled his way to numerous successful product launches. The weakness of the story is in the “why”. Because at this moment, there are millions of obsessive people like Steve Jobs, relentlessly pursuing a vision they believe is important. Only a very few – possibly – will change the world. Only a small percentage will make any difference. A slightly larger section will see the vision come to fruition in any form. And a large percentage will meet with failure. Or disappointment. Because if Steve Jobs is on the world-changing end of that spectrum, there are madmen with obsessive delusions of a cotton-candy elevator to Mars on the other.

The key difference seems to be what Stephen Covey identified as the 2nd “Habit of Highly Effective People” – begin with the end in mind. The advantage of Steve Jobs over a large corporation is that Jobs’ vision was crystal clear. A large corporation will rely on focus groups, surveys, project deadlines, budget analyses. Even if the need for the product (the “WHY it was built”) was clearly identified, the design decisions are confounded by too many variables. Jobs never experienced that. Sure, his projects ran over deadline and over budget and he alienated people and – let’s not forget – he was ousted for a few years from the very company he founded and made into a game-changer. But all of that was because he refused to rely on focus groups and marketing data and design decisions based on averages and “which of these is the least offensive?”. To Jobs, every element of the design – even internal components – were elements to be arranged with extremely conscious awareness, ever thinking of how it would integrate into the end-user’s life. For a man who could start and end relationships without so much as moment’s hesitation, Jobs seemed to forever be thinking about an amorphous, undefinable audience. How that one person – who represented every person – would use this product. And that vision trumps any collective decision-making process, no matter how well that process has quantified its decisions. Because no committee would ever be able or willing to justify a massive cost overrun to ensure that the polymer casing on the early Macs were the perfect shade of… tan. And that they had to be molded a difficult and specific way so that the tiniest lines didn’t clutter the aesthetic. Jobs knew to do that. He knew that the color would not only go anywhere and fit with any decor, he could envision what the end user might see in it: fields of wheat, pleasant and abundant and natural. And the lines, which would go unnoticed by a committee checking form over function, would have disrupted the aesthetic. Not consciously, of course. But on a subconscious level there would be the awareness of a design as clunky and functional as any piece of electronics. A simple line that makes the extraordinary ordinary. Only a designer would notice that. Only an obsessive would fight to eliminate that.

Even Apple could not maintain their standards. Within months of Jobs’ death, the new version of iTunes changed settings by default and most of the changes were as non-intuitive as anything Jobs ever mocked Microsoft for. It seemed to be “iTunes by committee”, which was particularly frustrating for me. When the iPod came out, I knew nothing about it, aside from the fact that it held many songs. As the owner of close to a thousand CDs, “more music” was exciting to me. I did not know how it worked, I did not understand how it worked, I was not sure I could import my CDs to it, but I knew I wanted one. When I got one for Christmas, I had no idea how to make it work. It took me all of two minutes to master it. I opened iTunes on my computer that day, and understood and mastered it in minutes. Yet, here I was, years later, a devoted fan, trying to figure out how to view a playlist on iTunes – an action I’d completed hundreds of times before. If I were to bet, I’d say the changes had been made to make things easier for the iPhone 5, and to accommodate programming changes without blowing project deadlines or cost overruns. Which is the way a committee works, not an obsessive.

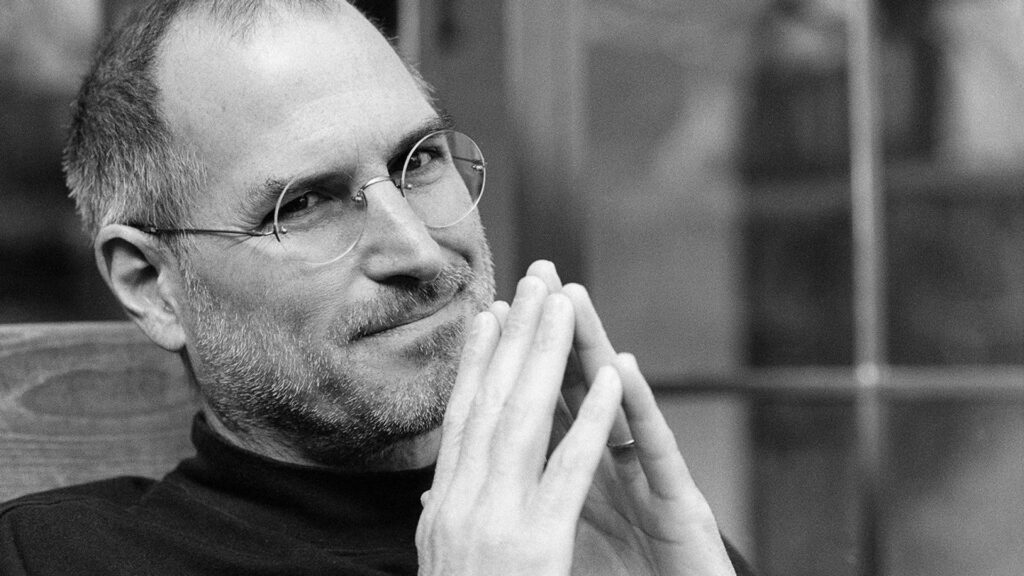

The curious thing about Steve Jobs (or any obsessive who creates something that people flock to) is that they consider their entire message. For Jobs, it was not just about what a product did. He also had to consider how it operated. How it looked while operating it. And how to create an environment to market that and showcase it. (Nothing does a better job of showcasing Steve Jobs design methodologies than the early iPod ads. People entirely in silhouetted, with the only “real” item being the iPod. Every man becomes Everyman, and the iPod is our universal connector. And not the iPod; it’s the music on the iPod that is our universal connector, because Everyman in the commercial is being moved by the music.) What Jobs recognized is that there are fundamental elements that tie us all together. That there are things that we all desire, things that make us human. The need to work faster and smarter. The need to connect with each other. The need to revel in the joy and freedom of art, and he considered every single aspect that went into making that better. It’s a deliberate and a painstaking process, and the fact that Jobs had to alienate so many people to get it done shows our collective lack of commitment to that.

If we’re being honest with ourselves, we don’t give our loved ones that much attention. We don’t give our children that much attention. We don’t obsessively, relentlessly, ceaselessly think about what we can say or do to make sure we’re providing the best experiences in life. We offshore our decisions to other people. We proxy our decisions to societal standards. We leverage the comfort of the committee more than we take a stand and say, “Dammit, I’m going to create the perfect experience for you, because I care!”

Because if there’s something to take from Steve Jobs as an influencer, it’s that you can design perfection. And you can do it repeatedly. But it takes effort. And more than a little backbone. And an amazing amount of belief in yourself. And you’ll have to muster all of that in the face of intense pressure from “committees” happy to relieve you of your duties and bring the project in on time and under budget. And hopelessly mediocre.

But if it matters to you, you begin with the end in mind. You envision the perfect world you want to create. And you fight for it – tooth, fang, and claw. And you bring it into the world as perfectly as you envision it.