The Muppets on Saturday Night Live: Final (full) appearance on January 17, 1976

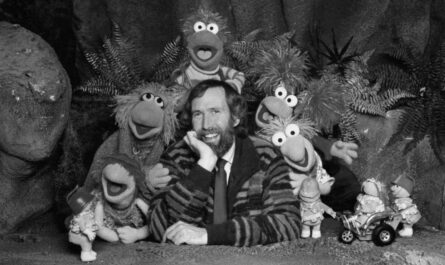

When Lorne Michaels first conceptualized Saturday Night Live in 1976, he imagined it as a live variety show. There would be sketch comedy and music, but also stand-up comedy, short films, and puppets. Michaels was a gifted producer with a great eye for talent, and he’d seen Henson’s Muppets on commercials and more mainstream variety shows like The Ed Sullivan Show and The Jimmy Dean Show. The humor on those shows was generally fairly cornball, vaudevillian humor. Jimmy Dean’s show was written by old vaudeville comedy writers, which was fine with Jim. He loved the silly, pun-filled stage humor filled with misunderstandings and sarcasm. But there was a technical wizardry to his puppetry that made the humor stand out. His puppets could do things no other puppets had done before, and the audience‘s “how did they do that??” amazement made the humor that much sillier, by contrast. Henson had always believed that Americans could learn to see puppetry as an adult art form, the way Europeans had viewed it for centuries. Henson’s first professional work was a daily show called Sam and Friends, which ran for fifteen minutes before the evening news in Washington, DC. Ed Sullivan and Jimmy Dean were his follow-up attempts to put puppetry in the adult mainstream, but all of the humor in these shows had been family-friendly. When Henson was approached by Joan Ganz Cooney to provide the puppets for Sesame Street, his main concern was that it could relegate puppetry to “art for children” in the minds of the American public. And he was right; it did. By 1976, Lorne Michaels was ready to challenge that perception. Not only could Henson do family-friendly humor, he believed Henson could competently create puppet comedy specifically for adults. Puppetry with a political and a sexual edge to it. For Jim, it was the culmination of a long-held dream.

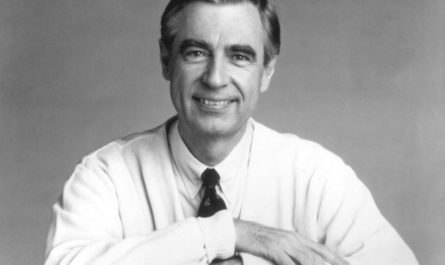

Unfortunately, it was not the dream of anyone else at Saturday Night Live. The cast was embarrassed to share the stage with puppets. The writers despised having to write “for felt”, as Michael O’Donoghue described it, and found Henson’s attempts to defend the characters both precious and pretentious. Worse yet, the live audiences were primed for a specific laid-back, Second City-inspired “cool” comedy; laughing at puppets wasn’t on the “cool” radar, and would happen only sporadically. Still, Michaels liked the idea, and “The Land of Gorch” appeared in each of Saturday Night Live’s first ten episodes. The Land of Gorch was a mystical land filled with archetypal characters that the writers and puppeteers would use to satirize popular culture. There was an overblown King Ploobis, who rules through arrogance and insatiable appetite. Ploobis’s shallow, shrewish wife Queen Peuta was constantly nagging Ploobis and was too self-involved to catch Ploobis’ ongoing sexual trysts with her “sexy” (by Gorch standards) female handmaid Vazh. Scred, King Ploobis’ sycophantic majordomo regularly inflated the king’s ego enough to scheme behind his back. And Prince Wisss was the stoner son who spent his time huffing toxic crater gases. In skits, they would refer to drinking, drug abuse, masturbation, infidelity, gluttony, governmental waste, and sex toys. Unfortunately, “refer to” is the depth of The Land of Gorch skits. While the rest of the show was infused with truly edgy satire, the writers would draw straws to see who had to write the Muppet sketch each week. The losers would toss together a traditional mix of silly slapstick peppered with bawdy references and corny jokes. It was a recipe for mediocrity, and far from the satirical edge of the rest of the program. After ten episodes and plenty of strained relationships, Michaels cut “The Land of Gorch” sketches from the show. For the remainder of the first season, puppeteer Jerry Nelson would pop up with the breakout puppet Scred, begging for The Muppets to be rehired. The season finished out with The Muppets as a running gag for failure, and Jim’s hopes for mainstream adult acceptance of puppetry dashed.

Artists are not the only people who bear the burden of “acceptance” to achieve their goals. Artists may be obvious examples, but most people who dream require some kind of acceptance to make their dreams a reality. Inventors need customers to buy their products. Chefs need people to enjoy their food. Almost any change we wish to make in this world requires someone to accept what we’re attempting, to encourage it, and to allow it to happen. Certainly, one can effect change without acceptance (war, genocide, theft), but for those looking to change the world in a productive manner, acceptance by others is required. If the world denies your influence, you’re not effecting change. Despite being the most famous puppeteer in the world in 1976, Jim Henson couldn’t effect the kind of change he dreamed of. And that can be soul-crushing. Never mind the high stakes Henson was playing with, it’s difficult at every level. It’s difficult for poets to get on stage and read their first poem. It’s difficult to quit your job and pursue your passion. It’s difficult to sing a song for an audience. It’s difficult to share a favorite recipe or to craft an emotionally honest letter. Because rejection is frightening enough; rejection when you truly want to make a difference can be devastating. And so it would have been understandable for Jim Henson to retreat to the world of children’s television where he had gained massive acceptance and was finding himself growing increasingly more famous and wealthy beyond his wildest dreams. Millions have retreated from their dreams from far less rejection. But Jim Henson wasn’t that type of dreamer.

Despite bad press and humiliating vibes from the staff of the show, Henson would always claim that his time at Saturday Night Live was a great learning experience, and merely an unfortunate ill-fitting. If he licked his wounds at all, it didn’t show. He merely stepped back and searched for a new avenue to create puppetry for adults. In modern business language, we hear of companies “pivoting” from one strategic direction to the next and finding success after a few aborted attempts. This was Jim Henson’s plan, forty years before “pivoting” became a bona fide strategy. He would continue to shift mediums and characters and formulas until something stuck. And he would regularly meet with the frustration of an unaccepting audience. Henson spent years of his life and millions of dollars making The Dark Crystal for adult audiences. When he first screened it for Universal Pictures, the film ended and they walked out of the room in silence. The film’s eventual lukewarm reception was difficult for Jim to handle, but he continued to plug away. He would try again with Labyrinth. He would try again with The Storyteller. He would try again with The Jim Henson Hour. The greatest irony is that as his life neared its unexpected end, he began to gain some acceptance by adults as a mature artistic medium. But like nearly everything he did, Jim Henson was simply too far ahead of his time, and he didn’t live to see puppetry become a well-respected medium. Avenue Q, a play designed and performed by former and current Henson puppeteers became a smash hit on Broadway. “Puppet Up!” is a live, adults-only puppet show put on by Henson puppeteers to hone their improve skills; it has been sold out in Los Angeles for years. The hippest “alt” comedians of today regularly host and appear on Fusion Network’s “No, You Shut Up!”, a mock current events panel show populated by cast-off Henson Muppets. Bands like Weezer have put The Muppets in their videos, and the entire Muppet movie franchise was rebooted because of the passion of actor Jason Segel and Flight of the Conchords musician/comedian Bret Mackenzie.

The difficult truth is, the world doesn’t want to change. Everything in nature follows the path of least resistance, including our own emotional states: that’s why rivers and people grow crooked. That’s why it’s difficult to lose ten pounds, and nearly impossible for a new cola to break into the market. It’s why Peanuts reruns run in newspapers fifteen years after Charles Schulz has died, despite the existence of thousands of talented living cartoonists. Humans like familiarity; we’re hard-wired for it. And so our dreams run contrary to our very evolution. We look to make an impression on a world that doesn’t want anything to change, and that level of conflict can feel overwhelming. It can feel like the world is against us, resisting our attempts to make a mark. And it starts to feel like it’s in our best interest to stop trying to change things. And so – sadly – many of us do. We go through our days trying to leave as little impact as possible. We avoid anything, positive or negative, that may leave an imprint. And we die, never having done any damage but never having changed things for the better, either. Jim Henson wasn’t going to allow himself to be one of those people. Despite the world telling him – over and over – just how little they wanted to see the changes he dreamed of, Henson kept dreaming. And he kept on searching for the right way to enact his dreams so that they would be accepted by the world.

Watching the first season of Saturday Night Live today, Jim Henson and The Muppets were the butt of a joke. A joke told by a world that didn’t want to change. But Jim Henson was the kind of dreamer we all should aspire to emulate. Because forty years later? The joke was clearly on the world, not Henson. Dreams can do that, if we’re brave enough to stick with them.