GREGG ALLMAN: Born December 8, 1947

OTIS REDDING: September 9, 1941 – December 10, 1967

In the early 1970s, Muhammad Ali had entered his 30s and his talents were being questioned for the first time in his career. Three fights into his post-suspension return to the ring, he was handed his first professional loss. Subsequent fights would go the distance, and in 1973 Ken Norton beat Ali for his second professional loss. The whispers of his career being over turned louder. Ali, for his part, drafted a new strategy. Ali would begin important fights with a right-hand lead. Right-handed boxers like Ali stand with their left side facing the opponent. They use the weaker left hand to jab and distract, waiting for the opportunity to hit with the more-powerful dominant right hand. But that left-hand’s role is critical. Because the right hand is on the far side of the fighter’s body from the opponent, any right-hand punch has much more distance to travel. A fighter has to use the left hand jab to distract an opponent, if only to find enough time for the right hand to travel the extra distance without being blocked. To lead with the right hand (without the left hand jab, first) is rarely done in professional boxing. Primarily because few boxers are quick enough to pull it off – particularly heavyweights. But Ali dismissed that idea. He had always been fast. Now he would prove it from the first moment in the ring. And it worked. Opponents were never ready for it, and the first few seconds of an Ali fight would be a powerful slam to the face that set the tone for the rest of the fight. If nothing else, everyone facing Ali knew that – even reduced to his most basic elements – they were battling a man who was fast and punishing and dangerous.

The fact that this analogy is exactly how I think of singing is not a stretch. I can’t think of a moment when I haven’t approached a microphone and not planned on the first notes out of my mouth being the vocal equivalent of a right-hand lead.

When I haven’t thought of those first few notes as my chance to let people know that they were in for a ride. When I haven’t stood at that microphone, listening to the notes drive forward, waiting for the second where the rhythm will trip the switch and I’ll jump in without defense or distraction. And in those last few seconds between plan and action, I always marvel at one thing: how empty I feel.

The emptiness that comes from singing is not, it turns out, entirely metaphorical. However, as I draw in that last breath, it always feels like the air I’m inhaling is filling in a the hollow shell of my body. As if someone had replaced the real me with a life-size fiberglass statue. Like the statue at the door of every Frisch’s Big Boy; it looks imposing, but it’s just a lightweight, empty shell. And once that shell is filled with air, the air doesn’t just pass my vocal cords and create music, it seems to swirl and whirl inside me. Before I can even expel it, it needs to create some kind of tornado inside of me, and when that tornado finally becomes too powerful to contain in the hollow shell of my body, I open my mouth, and that’s what the audience hears: an echo of a powerful tornado escaping from the giant cavern inside of me. Raw power, to be tinted and flavored with whatever emotional resonance I choose to add to it. But the emptiness is like an accelerant, making the sad notes sadder and the bright notes more hopeful.

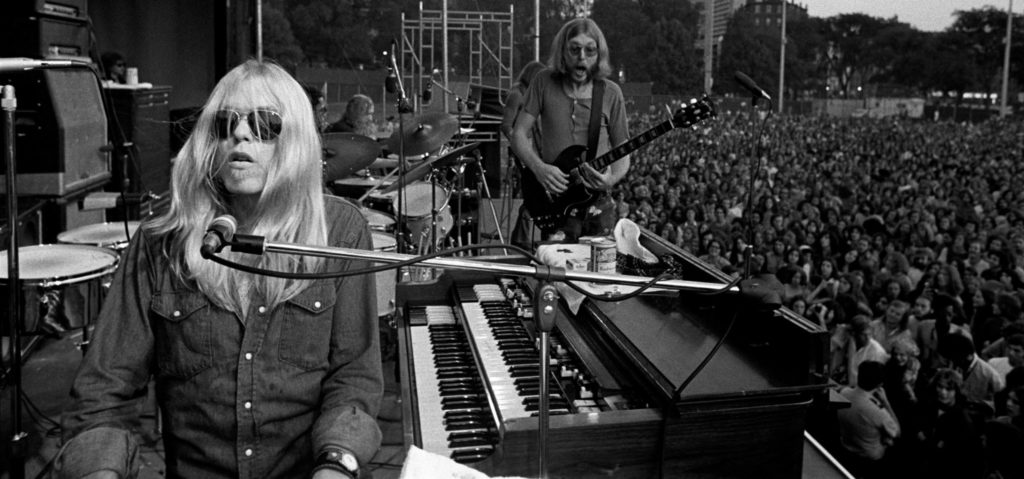

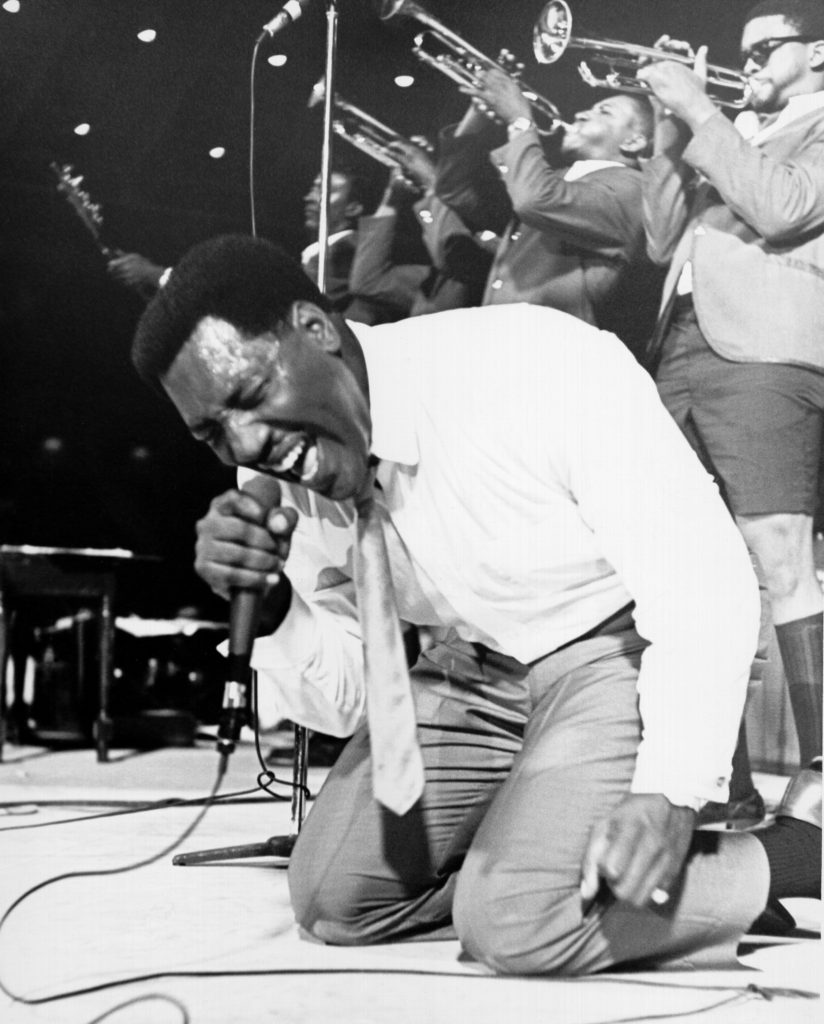

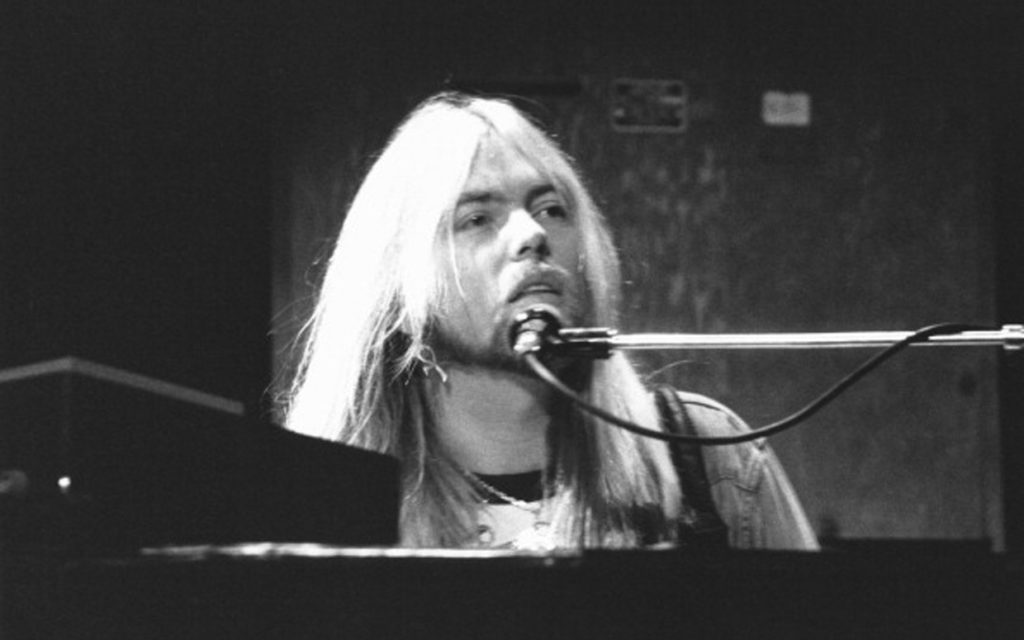

I was never formally trained in music. I played the trombone in junior high band, as well as you can play when you refuse to practice. As far as singing goes, though, everything I know about the voice and breath control I learned from listening to vocalists I loved and trying to imitate them. Two of the vocalists who affected me most profoundly were Gregg Allman and Otis Redding. To this day, it’s hard for me to pinpoint what I identified most with both of these artists. Like many things, there was a certain shock of recognition that went through my body the first time I heard either of them. I still remember both instances (my aunt had left an Atlantic Records sampler LP at my grandparents’ house when she moved out and “(Sittin’ On The) Dock Of The Bay” was one of the songs… my father owned The Allman Brothers Eat A Peach double-album. I remember trying to understand the gatefold art when Gregg began singing on the opening track, “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More”. All I knew when I heard these songs for the first time was how much I wanted to sing like those men. Perhaps it was the sadness in their voices that I connected with. Perhaps it was the first time I’d ever heard men sounding simultaneously vulnerable and defiant; their voices so powerful and gritty that it made the sadness seem more pronounced. Either way, I wanted to be like them.

I spent years learning to emulate the styles of Otis Redding and Gregg Allman (among others). Trying to make my voice sound more like theirs. Learning how to hold my throat, how to control my breath to give the notes the same aural resonance. What I learned (unwittingly) was technique. What I gained was so much more. Because the “empty” feeling that I learned was just a trick of vocal technique. It was a physical trick my mind played on me when I learned about intentional, diaphragmatic breathing. The peace that I felt was similar to the first calming glimpse of peace that comes with deep breathing to begin meditation. It’s why we tell hysterical people to take deep breaths. It’s calming and centering. Purifying.

But it’s from that calm, centered place that Gregg Allman and Otis Redding brought their true emotions forward. Technically, it’s the place that all singing comes from, but there’s a spiritual element, as well. Uncluttered by random or excessive emotion, Gregg Allman and Otis Redding could bring any emotion they wanted to the song, pure and unfiltered and complete. It’s the gift of technique, really. The technique clears us to be honest with the lyrics, and allows more of our own emotional state to run directly into the song. Because any singer ends up doing this. Kevin Federline and the singer from Right Said Fred followed the technique, but when stripped to that bare moment, there appeared to be very little emotion upon which they could build. Shallow people become shallow singers; the best can rely on technique to carry them through a soul-less performance, while others just grate away. Not so with the singers I love. Gregg Allman and Otis Redding, when centered and clear, had a blank canvas upon which to display their souls, and it was magnificent. And it roared and it echoed and it transmitted pure emotion. And it moved us, as listeners, as if we were experiencing the singer’s emotions, firsthand.

So when I sing, in the moment before the music’s intro ends and my first words are sung, I imagine the snap of the first line, as direct and honest as an Ali right-hand lead. And I imagine the look when an audience not only hears the lyrics, but feels them. The way I feel them. Because the song is coming out of me with the force of hurricane, sweeping up all of the unfiltered emotion I feel, joyfully churning and gaining power within the empty place where all music starts.