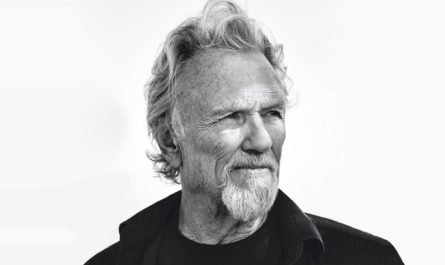

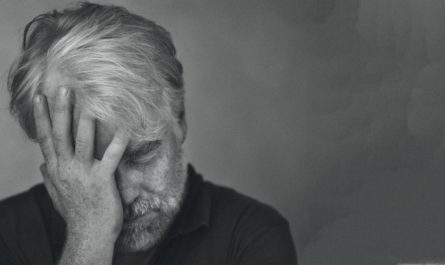

GEORGE MILLER: born March 3, 1945

A young friend of mine is a talented writer and cartoonist. He has the unpolished edge of all young artists on the verge of finding their voice, and he is prone to the kind of self-doubt that comes from regularly studying great works of art. It’s a defining period for a young artist. All artists start as imitators. They learn their craft by creating art similar to the work they most admire. But as an artist’s unique voice develops from this heavily-influenced state, the new voice feels distinct and unfamiliar. It may sound vaguely reminiscent of the influences the artist loves but it’s too unique to judge as good or bad. And since most artists have immersed themselves so deeply in their art that it has become part of their identity, their willingness to throw themselves behind an unfamiliar voice – even one coming from within themselves – is a huge risk. This is the critical decision point for artists. Do they embrace the risky and unfamiliar as a bold new artist, or do they retreat to certainty and influence and remain forever just a “fan of art”? It’s a crossroads I found myself at when I was young. (I chose the latter.)

But the strangest part of the new media landscape is how my young friend deals with this mounting uncertainty. He takes to social media and asks his friends and fans what they think. Should he write or draw more? What genre would they like to see most? Should he draw this comic strip or that? Both? What should he name them? Is there a storyline they’d like to see? It’s not just market analysis; it’s the crowdsourcing of creative inspiration. And I watch sadly from the sidelines because I know that nothing – nothing – will kill the creative muse faster than trying to anticipate how an audience will react to your art. Anxiety is nothing more than a brain desperately trying to manage an uncertain future. It is difficult enough for accomplished artists to overcome that sense of anxiety; for younger artists just coming into their own, it’s often insurmountable.

Yesterday, I wrote about how Lou Reed was unconcerned with the consequences of his creative decisions. Australian director George Miller had a similar take on art. He once said, “the audience tells you what your film is.” An artist can create whatever they desire, but in the end, the audience will determine its meaning. Trying to fight that will only lead to anxiety, but learning to accept it can free us up to create great things.

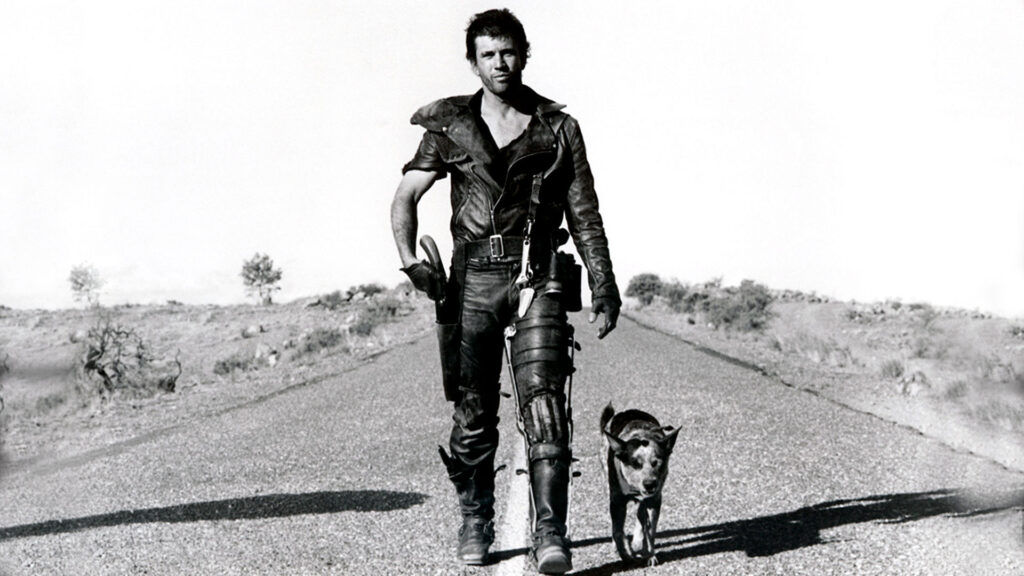

George Miller was the child of Greek immigrants raised in Brisbane, Australia. He graduated college and was enrolled in medical school with his twin brother when their younger brother mentioned a student film competition at his university. Despite being in his final year of medical school, George helped his brother create a one-minute short film that won the competition. As George worked through his residency, he met another resident named Byron Kennedy who shared his love of film. They formed a partnership with the dream of someday making films together in their spare time. By 1972, Miller and Kennedy had finished their residency and spent all their free time working on short experimental films. By 1979, Kennedy Miller Productions had produced several short films and the company had enough money from Miller and Kennedy’s doctor salaries to finance a feature-length film. Miller wanted to film a script he’d written a few years earlier about a police officer in a world growing increasingly short on natural resources and human kindness. Mad Max was Kennedy Miller Productions’ first feature in 1979.

Mad Max was not only an initial box office sensation (quickly becoming the highest-grossing Australian film in history) but to this day holds the Guinness Book world record for the highest return on investment ever for a movie. (The film has grossed over $100MM from a $350,000 budget.) It led to a studio film offer to make the sequel, Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior, which raised the bar for action films. Its success earned Miller the opportunity to direct the most recognizable segment of The Twilight Zone Movie, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet”. Three consecutive hits led to his biggest opportunity, the third film in the Mad Max series, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. Despite commercial success, the film was mostly panned by critics.

That was when Miller’s career began to take unexpected turns. He moved from action films to dramas. Miller directed a marquee picture for Warner Brothers, The Witches of Eastwick, then wrote and directed the critically-lauded commercial flop Lorenzo’s Oil. And then, logically, he switched to the Babe movies. Indeed, the director of the Mad Max series was also the writer of both movies in the Babe franchise (as well as the director of Babe: Pig In The City). He then followed those successes up by writing and directing Happy Feet and Happy Feet 2. And then he returned to the Mad Max universe in 2015 with the grittiest, most action-packed chapter in the series (and, for my money, the outright best picture of that year), Mad Max: Fury Road.

Fury Road was hailed by critics as a tour de force action film, and reviewers awkwardly (and sometimes misogynistically) noted the presence of a strong female lead, Charlize Theron’s character, Furiosa. Miller had intended the film to feel like an old Western serial saga, where the hero rides into the next town and gets swept up into their drama, and then moves on. In this case, the drama just happened to be about some women. For Miller, the film was an action film, and the production spent over a year planning for 120 days of filming on salt flats so that all the stunts, car crashes, and explosions could be real, and not CGI. The triumph of that film shoot is inescapable. It’s a post-apocalyptic world that is grotesquely unique, and yet we recognize ourselves in it. We can understand how this so-called “society” developed over the years. And in a world where material resources are worshipped and people are solely commodities, the violence of the movie is its only form of redemption, and Miller treats it with an almost holy sanctity. Sacrificial deaths – even by the War Boy villains of the movie – are gloriously symbolic and balletic. The risks taken by stuntmen in the movie becomes palpable to the audience. It’s a magnificent action film, but it quickly became apparent to audiences that the action sequences were less interesting than the fact that a Mad Max movie had a feminist message.

Miller was not opposed to the realization, and never disagreed with it or argued against it. But he had never set out with the intention of communicating a message of feminism, much less making a feminist movie. In his mind, the women were merely chattel breeding property of the dictator Immortan Joe, and so it made sense that a woman would help plan their escape. Miller once said of the feminist message, “it was never the first agenda of the film, it was always story-driven and the rest followed”. This is not to say that he didn’t think in feminist terms. A typical male-centric film director would have written and directed Furiosa as a male character who just happens to have female parts. Replace the female lead with a male lead and nothing would need to be changed in the script. But Miller knew that he wanted these characters to be very closely attuned to the idea that women were – and probably always had been – treated as property. And Miller knew he couldn’t (and shouldn’t try to) mansplain his way to that emotional state. So he called in Eve Ensler, the activist and author of The Vagina Monologues to workshop with the cast for a week, including large blocks of time spent with only the five female stars. It was an emotional tone that few male directors would have tried to achieve. (A good counterpoint is how Alan Parker – a very talented director – directed black actors in “Mississippi Burning”. The film was about the racist South, and yet every single black character was just sad and defeated, and waiting for white people to either save them or finally just leave them alone. The lack of self-determination in the black characters was often panned as a racist, despite its storyline being virulently anti-racist. Miller could have easily fallen into a similar pattern.)

Fury Road wasn’t the first time a Miller picture had received a different response than it was intended. After writing the hit movie Babe (and having some public disagreement about who should be credited for the film’s wholesome vision with director Chris Noonan), Miller decided to write and direct its sequel, Babe: Pig In The City. Intended to be a Joseph Campbell-like archetype of the young hero lost in a foreign land, Babe: Pig In The City became… something else. The city was cartoonishly dark and resonated with evil undertones. The hero’s journey throughout the film felt more like an escape from a nightmare. What audiences there were generally responded negatively. But then the film began to build a cult following. Film critic Gene Siskel called it the best picture of the year – in a year that included Saving Private Ryan and (the actual Best Picture) Shakespeare in Love. Over time, it developed a devoted following of people who saw it as a contemporary of Grimm’s fairy tales: dark and foreboding, but with a positive message at its core. It became a favorite of artists like Tom Waits.

Many directors in the past have bristled at audience reactions to their films. (Orson Welles with Touch of Evil, Tony Kaye with American History X, and David Fincher with Aliens 3 all come to mind immediately.) But what makes George Miller’s reaction so healthy is that he simply doesn’t mind. He’s not disappointed that audiences love a film he thinks is bad, as the previous directors all did. He cedes all control to the audience; ultimately, their reaction is the correct one. By relieving himself of the worry over what the audience might think or why, and by ignoring any impulse to control that narrative, Miller can make creative solutions that he trusts implicitly. He’s able to create the way he wants to. In the case of Mad Max: Fury Road, the final perception of the film is not at all what Miller had intended.

But Miller got to make the exact movie he wanted. And it was brilliant.

And the audience felt empowered and validated in a way that few action films had ever allowed.

When we just allow art to be what it is intended to be, everybody can win. When we don’t, we saddle ourselves with anxiety and lose the essence of why we want to create in the first place. I hope my young artist friend can learn this before that love turns into hopelessness.