DOROTHEA LANGE: May 26, 1895 – October 11, 1965

When you take an 80-day break from a project on “expresssing gratitude to ensure focus on the positive influences of your life”, there’s usually a damned good reason. But make no mistake, running underneath that reason are the simplest of declarations: “I’m not feeling cognizantly grateful” and “I’m not sure my influences are positive enough to reflect positively upon me”. But as I was driving around the central part of the state today with my kids, placing Memorial Day flowers on the graves of my grandparents and great-grandparents, we shared stories of our family history. Some funny, some serious, all pride-worthy. And in the quiet moments between counties, when the radio played a classic country song only I knew and all there was to look at was the fields of barely-sprouting corn, I had to face the difficult question that haunts me too often.

“Would my grandparents, great-grandparents, or ancestors be proud of the man I’ve become?”

When I tried to answer honestly, I never fared very well.

I’ve just come off a bout of respiratory and sinus infection and went to seek medical attention for the first time in a long time. I generally avoid medical scenarios because: (1) I’m overweight, (2) I live an unbelievably sedentary lifestyle, and (3) I generally avoid any kind of confrontation. After weighing in, the nurse took my vitals. The nurse read off my blood pressure. Despite being dramatically low into my mid-twenties, the numbers were now on the high end, nearing pre-hypertension levels. The nurse looked me up and down and said with genuine enthusiasm, “Hey! That’s not bad at all!”, the way one might marvel at the 35mph speed of a car they assumed could never run. As the doctor later examined me, she asked about my medical history. Diabetes? No. Heart disease? No. Each response met with a look that rested somewhere between “I don’t believe you” and “this poor fool probably doesn’t understand simple questions”. It was exactly the moment that keeps me from seeking medical attention in all but the severest of circumstances.

It was the moment where the face of the doctor suddenly reflected the many elephants in the room and the skeletons in the closet. It was a moment where I felt like somebody truly saw me for who I am. And I don’t want to be reminded of the person I am – my many failures and shortcomings. But sometimes in life, we simply must see the reflection of the person we don’t want to be.

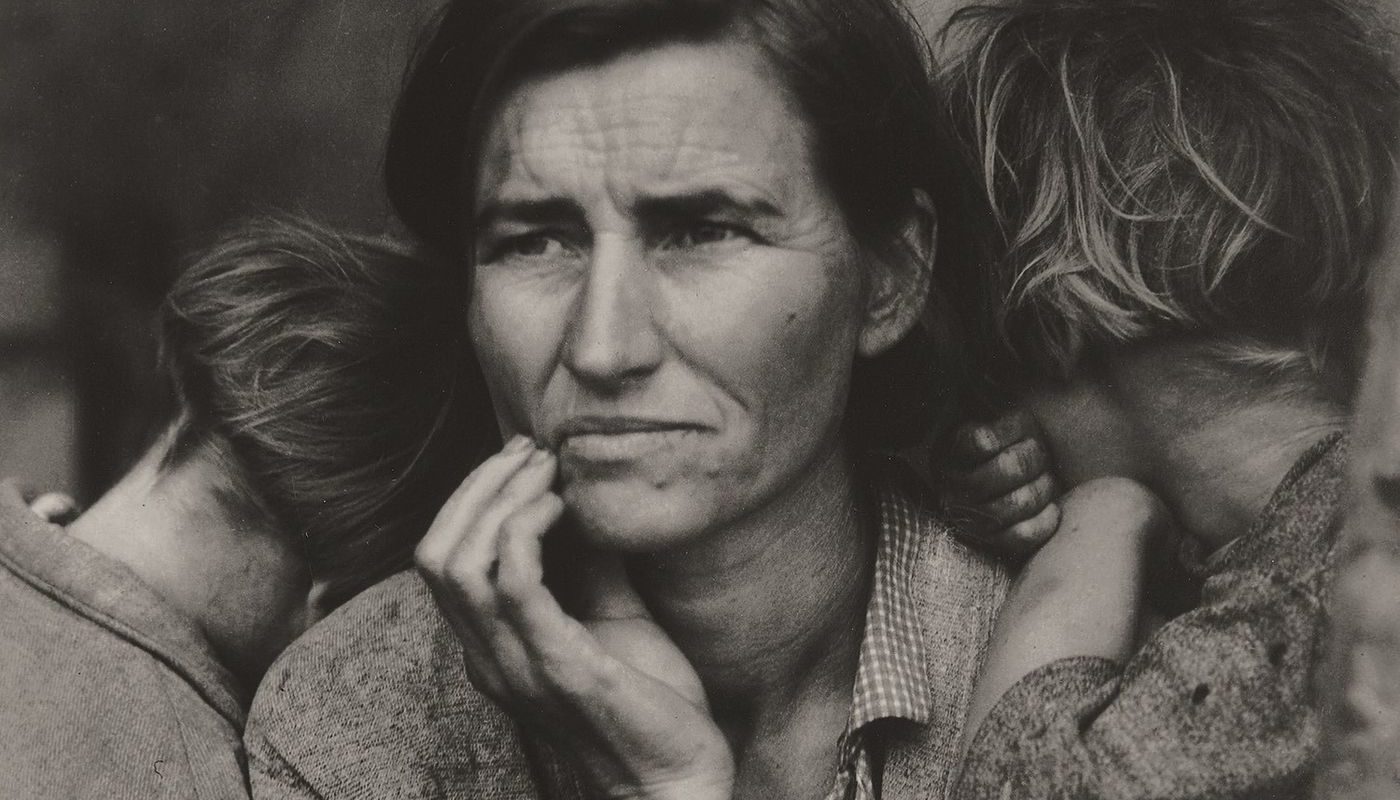

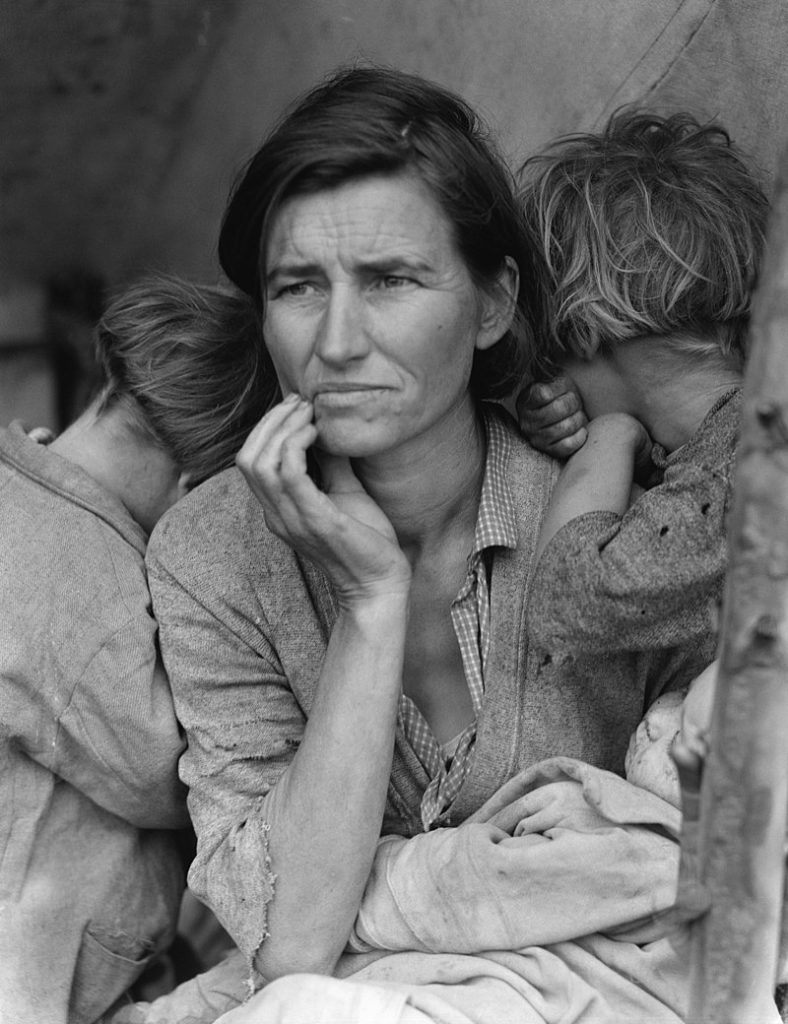

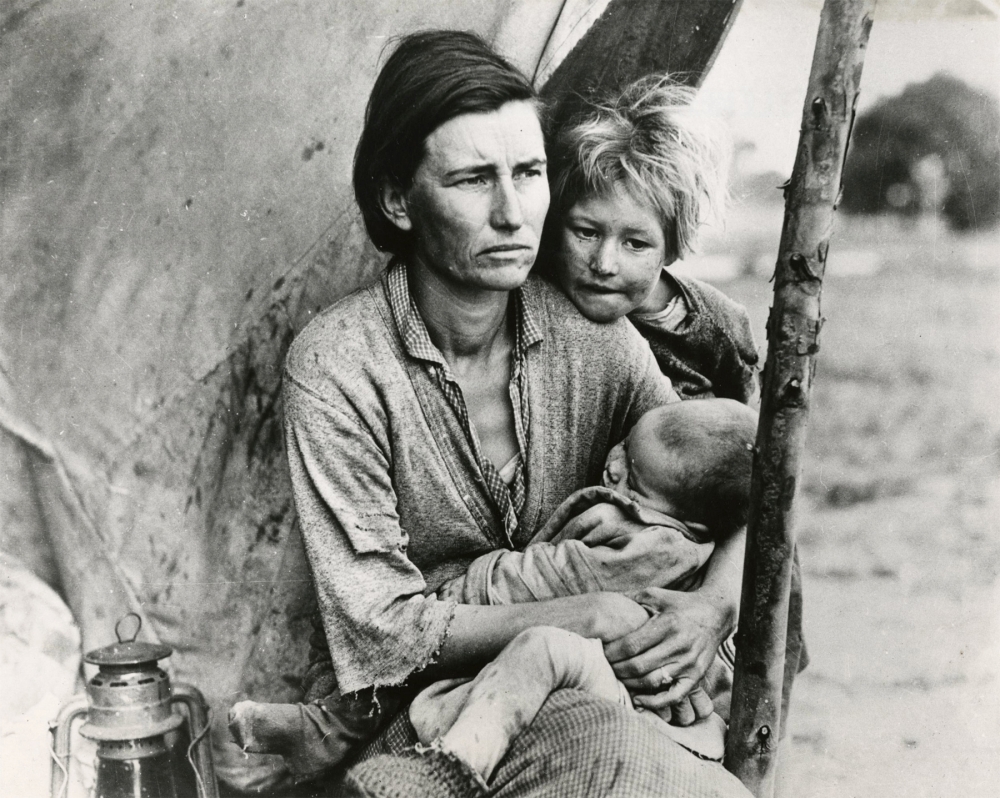

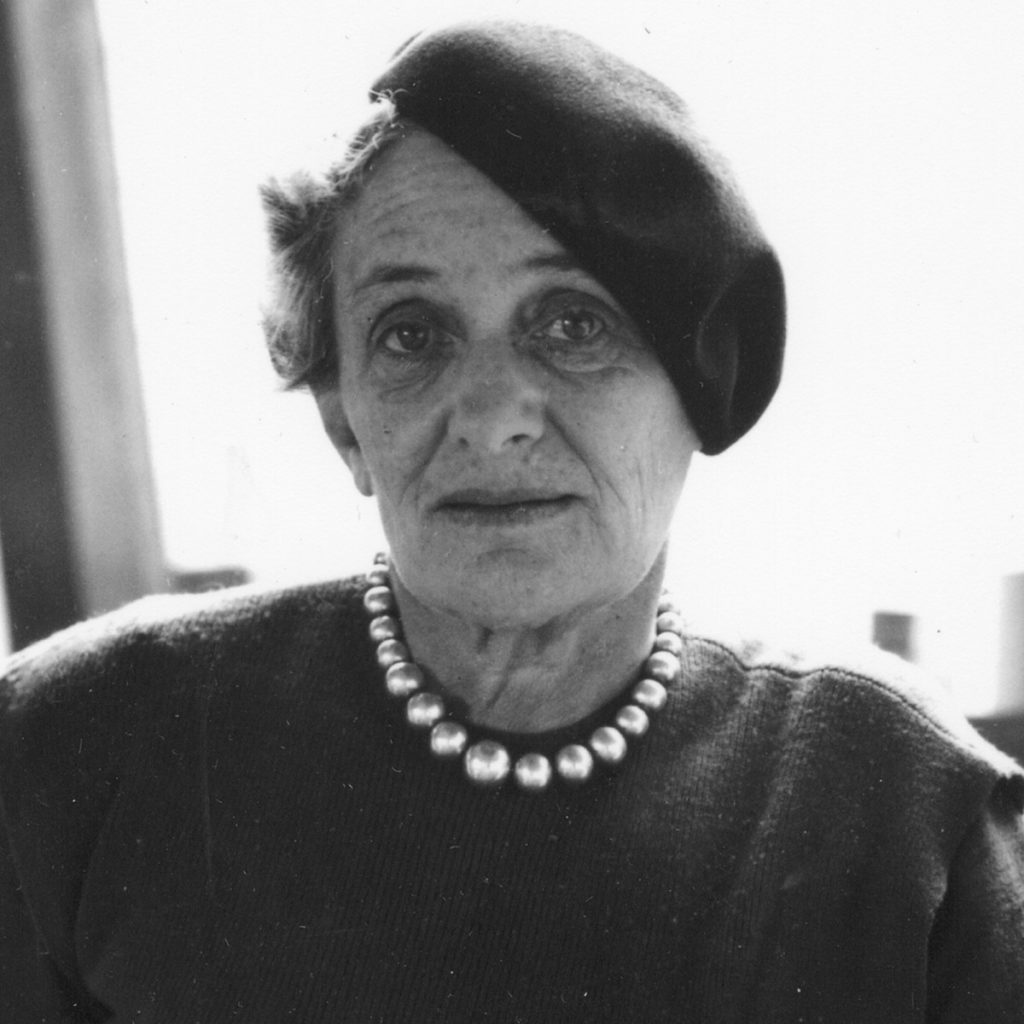

Dorothea Lange was one of the most influential documentary photographers in American history. Born in 1895, she contracted polio at age 7 which left her with a withered leg, a club foot, and a severe limp. Five years later, her father abandoned their family. Yet despite her gender and physical disability, Lange persevered. She dropped her father’s surname (Nutzhorn) and adopted her mother’s maiden name. It was a time when women did not regularly attend college, or have careers. Yet she graduated from Columbia University, apprenticed with notable photographers of the era, then moved to San Francisco and opened her own successful portrait studio – all before she was 25. When she was 40, she married her second husband, an economics professor at Berkeley, and the two of them began documenting rural poverty for the Farm Security Administration. Among the many popular photographs Lange took during this period is the now-iconic Migrant Mother, a photograph of migrant farm-worker and mother of seven children Florence Owens. The portrait shows Owens under a lean-to canvas tent in a California pea-pickers camp; she holds a baby in her lap as two of her children lean on her shoulders. Like much of the poverty-related portraits of farm workers of that era, it focuses on the misery of the life of a migrant farm worker.

But one of Dorothea Lange’s favorite sayings was “A camera is a tool for learning how to see without a camera.” What we see at first glance is misery. Tired children. Dirty people. A worn-out mother. A makeshift shelter. It is what we would see with a glance. It is what we would see if we were to pass Florence Owens and her children on the side of the road. It would be the initial impression we would make before allowing social decorum to avert our eyes. But as Lange stated, a camera allows us to see in a different way. With the time afforded us to see Florence Ownes, we pick up other things. Notably, that despite the dirt and the tattered clothes, Owens is a striking woman. (Throughout her life, Owens was a beautiful woman who had many wealthy and handsome suitors and husbands.) Upon examination, the pained look in her eyes is possibly a squint against the California sun. Most importantly, Owens’ children are with her. Widowed or abandoned a number of times in her life, Owens knew that asking for government assistance would likely result in having her children taken from her. So she resisted the urge to ask for help; just having her children with her indicates a personal strength that is inaccessible with a quick glance.

It seems contradictory that any of us would need to learn how to see without a camera, as Dorothea Lange suggests. Yet we do. Whether it’s the social rules that tell us not to stare at anything too long, or deeper prejudices that lead us to false conclusions, we’re constantly guided by interpretations what we perceive… even though that perception is – at best – limited. Because even when we try to hold the gaze, there’s no guarantee we’re focused on the right elements. Because when I asked myself if my ancestors would be proud of me, I found plenty of evidence to suggest they wouldn’t. Looking at my own life, I saw the dirt and dust and strain and the weak shelter. And I stopped looking. I’ve always stopped looking. And the truth is, after years of disagreeing with those who love me most about the strength and beauty I possess underneath the top layer of dust and strain, many have grown tired. When we refuse to see ourselves with the leisurely high-definition gaze of a portrait – every crack and bruise as well as every profound muscle and captivating feature – we create a disconnect with everyone who looks at us. And in some cases, we create an inferiority complex that others can’t see, but because we refuse to look at ourselves closely enough, it’s a complex that can’t be resolved.

While teaching photography in the 1950s, Lange regularly assigned her students to take a photo of something profound and defining from their home. The students goaded her into doing the assignment, as well. Despite a successful career, national acclaim, and iconic work, Lange returned with a photo of the thing that most defined her. It was a portrait of her twisted foot. To everyone else, Lange’s foot was noticeable, but a tiny part of the portrait. Looking at her life from the oputside, it was a feature, but not the definition of the woman. And yet, to herself, it was profound and defining. But we our not our biggest limitation. We are not our greatest success. We are not just the look in the doctor’s eyes, or just the negative traits our ancestors would dislike. We are not the stories we tell ourselves to deny the parts of the portrait we don;t have the courage to address.

Until we learn to look with the focus and timeliness of the camera, we’re all looking at the same portrait but holding separate conversations. And nothing is lonelier than that.