RAGING BULL: Premiered nationwide December 19, 1980

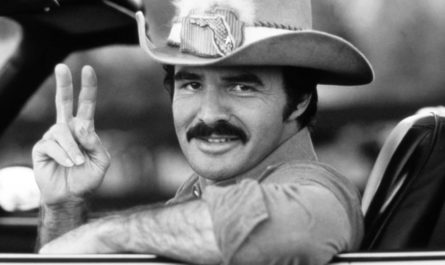

Of all of the movies I’ve seen in my life (a lot of them), Raging Bull has been in my list of Top Five favorites for many decades. At the time it was filmed, Scorsese had kicked a cocaine habit that had nearly destroyed him. Having suffered a critical drubbing for his musical New York, New York and directing The Last Waltz only as a favor to his friend and former roommate Robbie Robertson, Scorsese entered production of Raging Bull certain of one thing: this would likely be his last picture. Further complicating the issue was the fact that Scorsese hated sports, particularly boxing. And when he had tried to read LaMotta’s autobiography, he could never get more than a few pages before he was too bored to continue. But as production began, Scorsese found himself identifying more and more with Jake LaMotta, which was surprising. LaMotta was an animal. His appetities and his brutality guided his actions, and his desires eventually scared away everyone important to him. The script’s story arc showed LaMotta reaching the pinnacle of the boxing world, and losing it all. But even when he held the crown, LaMotta was miserable and out of control and driven by demons that robbed him of the middleweight crown. And then robbed him of his family. And then his freedom. And then his dignity. And while Martin Scorsese may have had an understanding of demons and self-destruction, the obvious comparisons ended there. And yet, as production went on, Scorsese (and Robert DeNiro) kept tinkering with the script until eventually, the filmed version was almost entirely their story, and not the story of the many screenwriters who had written early drafts. And from the script, one of the greatest sports movies of all time was written by a guy who hated sports.

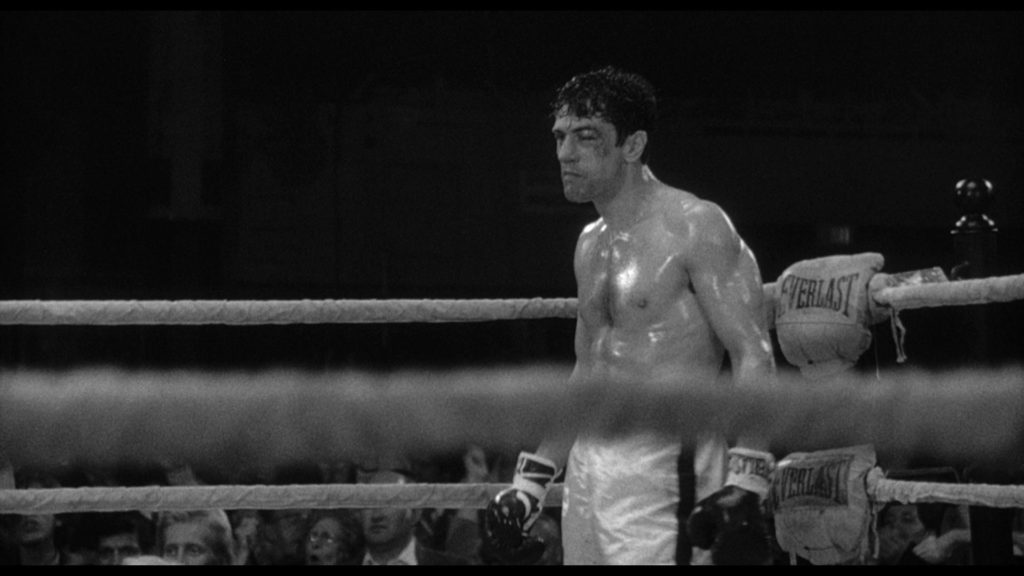

My reaction to seeing Raging Bull was very similar to Scorsese’s. My background and upbringing and life experiences couldn’t have been more different from Jake LaMotta’s, yet there was something in the character I always fundamentally understood. There is a defining moment in the movie for me. After suffering a brutal beating at the hands of Sugar Ray Robinson, a massively-bloodied Jake LaMotta stumbles over to the champion after the fight and taunts him. “I never went down, Ray. I never went down.” His feet slip on the blood he has spilled onto the ring, and his brain is scrambled and his words are slurred. But he never went down. He stood and allowed the middleweight champion of the world beat him mercilessly, but he never went down. And he taunts his assailant – the victor in their battle – as being too insignificant a man to knock him down. The scene probably registered as crazy or odd to most people. To this day, I remember how much I felt like cheering when he mumbled those words.

In my early twenties, I taped a print of a Civil War-era tintype I had cut from a book onto my closet door. In the picture, a former slave sat shirtless, photographed from behind. His back was a cross-hatched nightmare of brutal scars. Most of the skin had been whipped from his back at some point, and yet, in the photo, his pose is almost defiant. His hands at his hips, elbos out wide, his head held up and he turned to show his profile in the shot. Unapologetic. Unashamed. This was the portrait of a man who had withstood unimaginable punishment, and had come through the other side physically stronger, with a back less capable of tearing now. To maintain his dignity through that, and to come through stronger, was inspirational to me. I taped the photo to my closet door as a reminder and as an analogy for how I viewed life. “You can beat me all you want. It will only make me stronger.” It wasn’t until I was in my thirties that my wife helped me see that this was a terrible analogy for life. One day, she simply said, “You know, there’s a difference. You have a choice. You choose to let people whip you.”

There is a certain personality type that seems to find their center through the punishment they can withstand. To Jake LaMotta, “not going down” was more important than the heavyweight title. Because if you are one of those people, there’s a comfort in knowing what you can handle, and a certain mistrust in what the world bestows upon you. A middleweight title is a middleweight title. It’s a thing you get and a thing that can be taken away. Late in the movie, desperate for money, LaMotta takes a hammer to the belt to break free the gems embedded in it. He rushes the gems to the pawn shop to sell them, but the pawn broker isn’t interested. He wants the belt, which is a rarity and a privilege. To LaMotta, who earned that belt through years of toil and blood and sweat, the only value in it was intrinsic. The meaning around those gems was pointless, something he could crack with a hammer. The type of person I’m talking about can never reconcile the accolades of others. The belt was valueless to Jake LaMotta; what mattered was that he never went down. Martin Scorsese probably never took a punch in his life, but he understood that part of LaMotta. I am wildly different from both of them, but I understand that part of LaMotta. In my bones, I understand that part of LaMotta.

In one of the most famous TEDTalks of all time, psychological researcher Brene Brown discusses vulnerability. And one of the key theories she posits is how “certainty” is the obvious defense mechanism against vulnerability. That uncertainty makes us feel vulnerable, and that humans prefer the certainty of false logic and specious arguments and bullying because it makes us feel less vulnerable. As I watched that TEDTalk, I recognized how much that applied to me. It applies to Jake LaMotta, as well. Most likely to Scorsese, too. Watching Raging Bull through that lens, you see LaMotta bristle every time he feels vulnerable. When he fears his wife pulling away or worries that she may leave him, he rages and attacks. When he worries that his brother might not support him whole-heartedly, he rages and attacks. When he fears another man may steal his woman, he rages and attacks. To Jake LaMotta, there is an entire universe that is nothing but vulnerability. And his only way to control it is through certainty. Nothing about LaMotta is subtle or delicate. He gets a tiny nagging suspicion of some possible warmth between his wife and his brother, and he immediately accuses in wildly inflammatory tones. LaMotta’s life is a search for certainty in a world that regularly demands vulnerability. That was the source of LaMotta’s constant rage. And his certainty was found in his ability to withstand it. As I said before, there is a certain personality type that seems to find their center through the punishment they can withstand. Jake LaMotta could only feel invulnerable when he knew he could withstand what the world had to offer. I understand that feeling.

But in reality, that is not a life of invulnerability. It’s merely a life of denial. Keeping the wolves at bay as long as possible and then surviving any attack they can muster is probably not the best way to manage a life. Particularly if one can learn to live in relative harmony with wolves. But foe some of us, that part comes hard. Perhaps it’s the belief that we don’t deserve to live comfortably. Perhaps it’s a mistrusting belief that comfortable coexistence isn’t possible. Perhaps it’s just a ceaseless anger that always reminds us that we don’t fit comfortably in this world. But whatever it is, we guard ourselves constantly and await the inevitable, and we convince ourself that our greatest gift to the world is our ability to withstand whatever the world has to offer. And we won’t even be angry at the world. Or bitter. Because the world is just doing its job. And we’re doing ours.

I don’t remember the critic, but some critic mentioned a shot from the film where the camera focused on the rough, canvas-covered “rope” (actually a steel cable) that surrounded the ring. LaMotta had been leaning on the rope as he took a beating, and the rough canvas has torn into his as effectively as the man who was beating him, and the rope was now covered in blood. The critic stated that what made the shot powerful was the realization that, if the rope looked that bad, imagine what the man who had been torn apart on it must look like. But the truth is, the man who bled on that rope would never consider the rope at fault. Nor would he consider the man who was pummeling him into the rope at fault. That’s just life.

And it’s no way to live a life, certainly. But to some people, that myth of invulnerability is the only way that makes any sense.