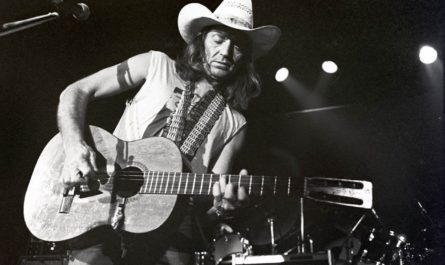

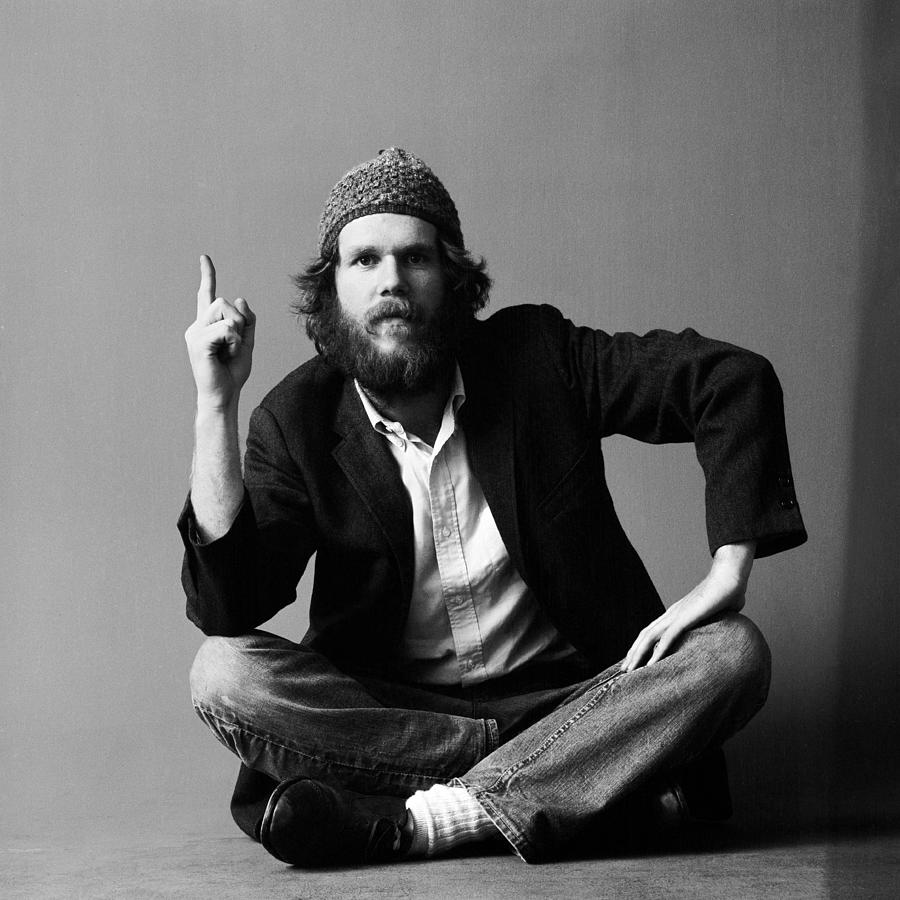

Loudon Wainwright III: born September 5, 1946

I’ve always been a sarcastic person. I come from a sarcastic family, and I generally find sarcasm funny. But not when it comes to art. Something about art feels too important, too sacrosanct to me to be treated sarcastically. Throughout my life I’ve discovered bands whom I desperately wanted to like, bands with extraordinary talent and flashes of true genius, but who always revert to a sarcastic tongue-in-cheek pose that screams, “We’re not taking this very seriously.” And some of that may be a pose. Sarcasm and disaffection – the act of looking down your nose at something you’ve created – may spring from that same well of insecurity we’ve all had since childhood. It may be that push-pull of the intense desire to be accepted and understood, balanced with the freedom beyond being hurt by others. As boys, we insult the girls we find ourselves attracted to. As teens, we roll our eyes at the first glimmer of promise in an activity. Enthusiasm and vulnerability are reserved for the experts, for the confirmed. Which is understandable in a 15-year old, but I have no patience for it in an artist, especially a talented artist. Which makes my fondness for Loudon Wainwright III pretty unique. Because of all of the bands I really want to like but can’t (Pavement, They Might Be Giants), Wainwright is the most sarcastic of the bunch. He’s the kind of artist who watched his infant son Rufus breastfeed, and described the strong bond between mother and child – and his own lack of that connection – with a song called “Rufus is a Tit Man”. The song was a sarcastic, silly chuckle-fest, in which Wainwright ends up admiring the connection so much that he dreams of breastfeeding beside his infant son. It’s a silly ditty with lyrics as childish as “Yeah, you’ve got the goods, mamma / Give the little boy a squirt”. But as silly as it is, Wainwright still manages to articulate the undying (yet often neglected) need for comfort and touch and nurturing, he tried to resolve the triangulation that occurs when “husband and wife” turn into “father and mother”. But he did it with an attitude that says, “This is all so silly, but I’ll write about it anyway.”

So, I should dislike Wainwright’s music. And I’m not sure why I don’t. I would be hard-pressed to call myself a “fan”, and I rarely play the albums I own. However, in the last few years, I have found myself drawn increasingly to his song “Motel Blues”, off his 1971 album, Album 2. It was an album written before Wainwright’s brief and stormy marriage to Kate McGarrigle crumbled, a period he would mine for songs for the next 40 years. In the song, Wainwright is narrating his life as a touring up-and-comer on the music scene. The song is a deconstruction of all of the rock & roll myths we’ve come to know. It’s the anti-Keith Moon story, with not just all partying ending early, but all activity:

In this town, television shuts off at 2,

What can a lonely rock & roller do?

In the song, the narrator is trying to talk a young woman who kissed him after his show into spending the night with him. And his argument showcases just how unglamorous life on the road was at that time. The highlights of the evening, he boasts, include a styrofoam ice bucket full of ice, “lots of soap and lots of towels” and promise that “I’ll buy you breakfast”. The song has no chorus, just a villanelle-inspired consistent theme in the final line of every verse – lines which swell with emotional need as the song goes on. In the first verse, Wainwright makes a vague offer to an unidentified (alleged) nineteen-year old fan: “Come up to my motel room / treat me nice.” By the second verse, he’s hinting at a desperation and loneliness. The loneliness of late-night drunken phone calls and staring at blank hotel walls. “Come up to motel room / sleep with me”, he begs. By the end of the song, the narrator is trying to assuage every fear the young girl has. He evokes the Bible in the dresser drawer, and he promises to shield her from prying eyes by making sure the “Do Not Disturb” sign gets hung. The final line of the song is the narrator begging, “Come up to my motel room / save my life.”

As Wainwright grows older, he has looked back on the often-painful incidents he has written about in song, and despite painting them with a sardonic brush (helped in large measure by Wainwright’s verbal tics on-stage – his knees jerk wildly and his tongue often shoots out of his mouth uncontrollably – which make the songs seem both more comical and more sinister), they are clearly profound moments. Often profound moments of great pain. And to hear Wainwright describe it, his songs were just an exploration of one question: “Is it necessary to feel like shit in order to be creative? I’d say the answer is yes.” For Wainwright, writing songs was the outcome of an unhappy life – a “way out of hell”, as Artaud called it. But from all accounts, Wainwright’s life was – for many years – an endless cycle of bad behaviors that ensured misery, and deliverance through song. Wainwright spent his life creating a sad fertile ground from which he hoped to bloom in temporary salvation.

But “Motel Blues” is more than that. Unlike all of his other sardonic, sarcastic, silly work, “Motel Blues” is a meditation on the connecting power of art. If the entirety of Wainwright’s catalog is a study in writing one’s self out of misery, “Motel Blues” is the point of the sword, when we escape our own isolation and finally connect with another person. Scholars have argued over the purpose and true nature of art, but I personally have to believe that all art is created with the intent of connecting with other people. To create a symbol of a momentary worldview that we share with others in hope that they will understand. The “Motel Blues” narrator is clearly well-versed in that connection. It’s the end of the night, and he’s laid his soul bare and as the club empties and he faces a night alone, he starts to work a young woman to stay with him. He plies her with hotel amenities, and eventually a promise to write a song about her. For the first two verses, Wainwright appears to be commenting on the connective power of art in a basic manner; the narrator is just trying to find someone to sleep with him. But in reality, the third verse is the most honest. By accepting his offer, the young girl can “save his life”. In that moment, everything hinges on that connection. Without her acceptance of him, he may not even continue to exist.

That’s the message of “Motel Blues”, and – for me – the message of art. That we create to reach others and share our view of the world with others. Because when we’re creating ourselves out of hell, we’re not completely out if we find ourselves alone. Loudon Wainwright III never seemed to be able to communicate that without making a little fun of it. I should hate that, but I don’t. Because I understand it. Because I connected with it. And maybe, for a moment, that acceptance saved his life.