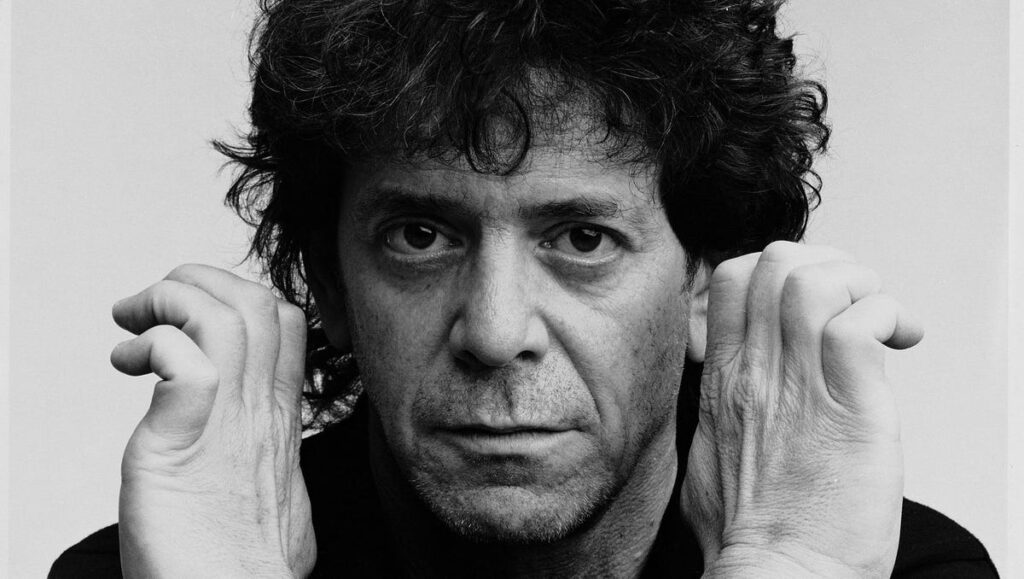

LOU REED: March 2, 1942 – October 27, 2013

If there are two words more needlessly misused and/or overused in America these days than “cancel culture”, I’d be very surprised. Just this week, US Representatives attending CPAC demanded a Judiciary Committee investigation into “cancel culture”. On the left of the political spectrum, Bill Maher performed an ominous monologue on his show Real Time about the imminent threat of “woke culture” and “cancel culture”. In the monologue, he shared a study that said that 62% of Americans were afraid to share their opinions for fear of being “canceled”. But “canceling” has become one of those ill-defined euphemisms that inflate the mundane into something (allegedly) world-ending. Because the examples of “cancel culture” run amok are, for the most part, not really career-ending. Even Colin Kaepernick, who literally lost his career when he was canceled, still has lucrative endorsement deals with Nike, Beats by Dre, McDonald’s, to name a few. Is he making as much money? Of course not. But he’s far from “canceled”. Same with Ellen DeGeneres. And Sebastian Stan. And Louis C.K. All of them kept working (although to a lesser extent) during their “cancellation”.

As did J.K. Rowling.

And Morgan Wallen and Lana Del Rey and Jimmy Fallon and Doja Cat and Lea Michelle and Shane Dawson. And so on and so on.

The truth is, “cancel culture” is really more just “consequence culture”, where either society or a corporation’s bottom line chooses to distance itself from someone’s bad behavior, and extends some consequences. Sure, their wallet takes a hit, and yes, their calendar opens up. And I’m sure there is the occasional heckle or public confrontation, but I have yet to see any true “scorched earth” cancellations. These complaints are from people who want to say and do whatever they want but avoid any consequences. Which is pretty much the exact opposite of how the late, great Lou Reed lived.

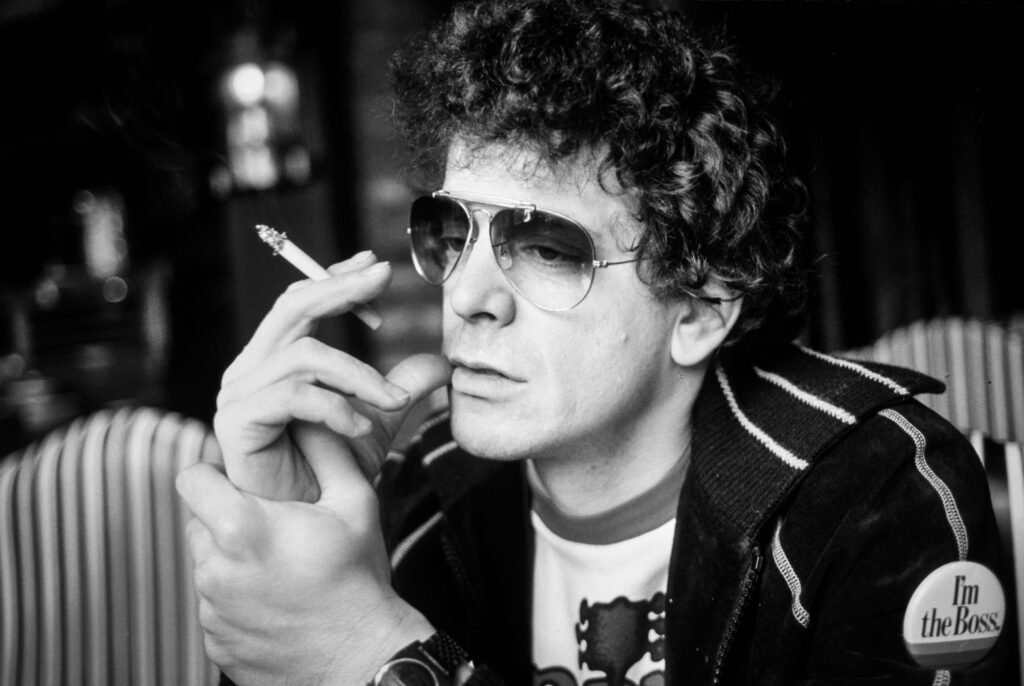

Lou Reed’s career was the epitome of “consequence culture”. When he died of liver disease in 2013, countless epitaphs paraphrased the idea that Lou was “the most influential musician most people had never heard”. Brian Eno once described The Velvet Underground, Lou’s first band by saying, “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band.” Lou was an influential artist primarily through his talent as a songwriter (and mostly as a lyricist), but it was also his fearless lack of concern for the consequences that made him iconic. He was one of the godfathers of punk, though he never played punk music. He was an early influence on glam rock, though his music was too dark and gritty to ever become standard glam fare. He was a classically trained pianist and theorist and constructed intricate arrangements that he muddled with lyrics of decadence and depravity. He was a Syracuse-educated poet who mentored under Delmore Schwartz but also wrote lyrics like, “Good morning, it’s possum day / Feel like a possum in every way”.

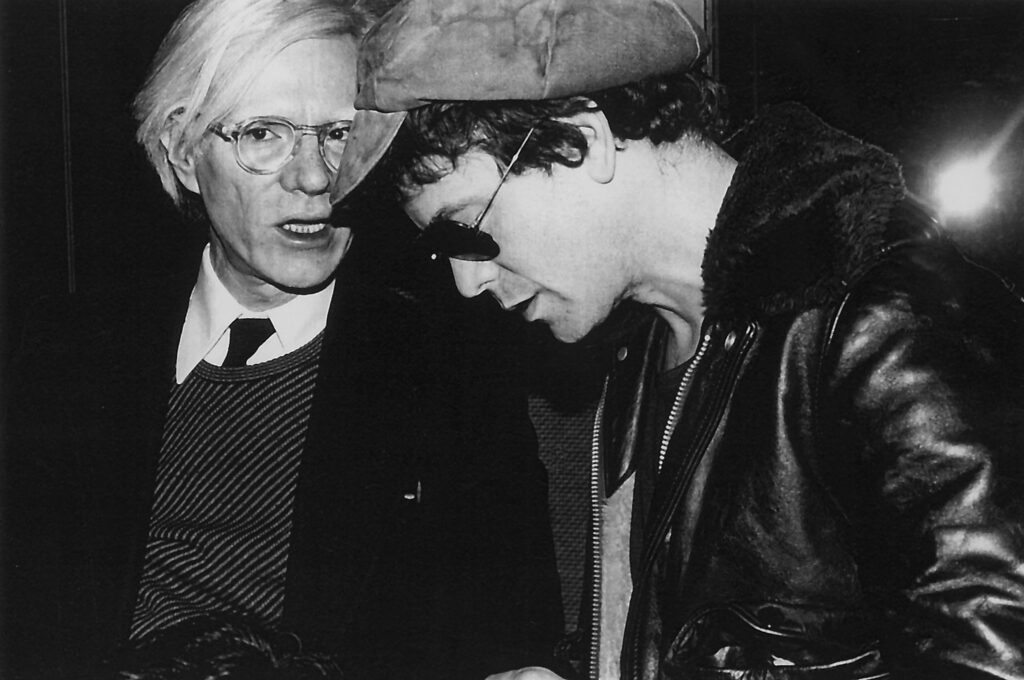

Because Lou never seemed concerned with consequences – only with creating on his own terms. When The Velvet Underground was formed in 1964, the band played local coffeehouses and galleries until they were discovered by Andy Warhol (whom Reed and bandmate John Cale nicknamed “Drella”, a portmanteau of “Dracula” and “Cinderella”). Warhol brought in German actress and singer Nico and produced their first album. From an engineering standpoint, Warhol did little more than press the ‘Record’ button in the studio. But his influence as a producer was more about how he allowed the band to feel. Warhol encouraged any and all creativity from the band, and for a band of five boundary-pushing artists, the album was iconoclastic – “the most prophetic rock album ever made”, according to Rolling Stone. This was their album, and signs shined simultaneously as examples of collective and individual brilliance. Reed’s lyrics were also notably groundbreaking. Much like the Beat poets of the 1950s, this was the first time a rock album situated itself firmly in a world with drugs, drug abuse, and all manner of sexual deviancy in it. The album was a commercial failure (and widely overlooked by critics), but it shaped Lou. It gave him a sense of what it meant to create without considering the market: how to sell the work, whom to sell it to, and what to tailor to make it more appealing to a mass audience. In fact, Lou went the exact opposite way. The next three Velvet Underground albums were created under a similar ethos. (Though the band was no longer produced or managed by Warhol. Nico also left when Andy did.) The lack of commercial success (or even acknowledgment) wore heavy on the band. Cale left after the recording of the second album, White Light/White Heat, and Lou quit the band after the recording of the fourth album, Loaded.

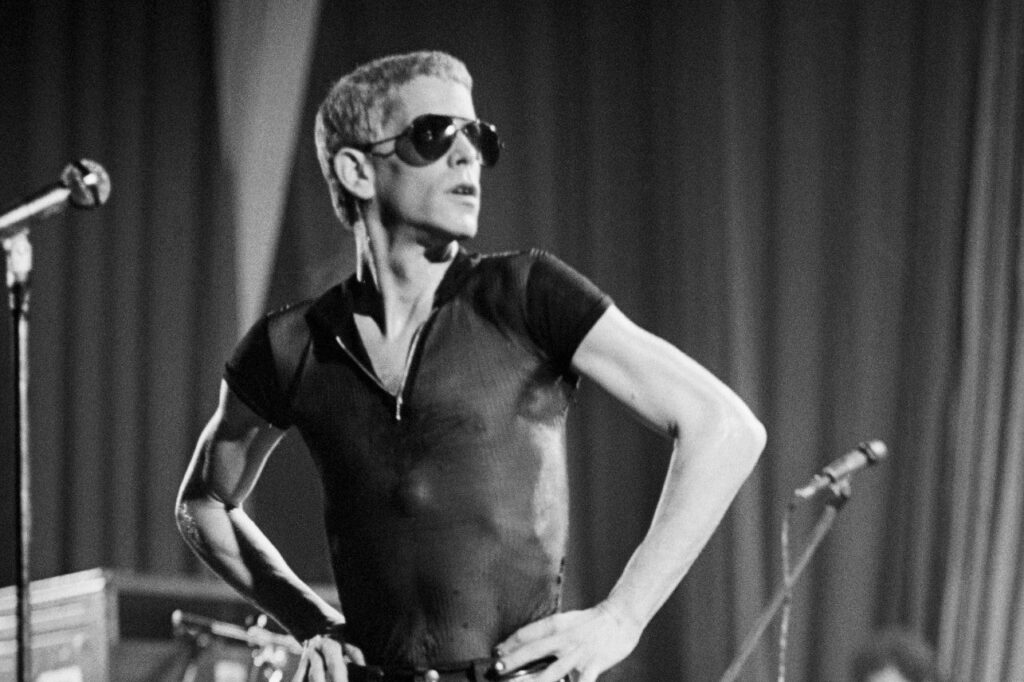

If The Velvet Underground was where Lou Reed got his first hit of the intoxication of art, his solo career was the protracted addiction. Of the six original albums in his initial contract with RCA Records where Lou had creative control, all defied expectations and confronted norms. He debuted by re-recording Velvet Underground songs with prog rock pioneers Rick Wakeman and Steve Howe from the band Yes. Just as audiences got used to Lou Reed on his own, he created a seminal glam rock album, Transformer. The album was produced by David Bowie and Mick Ronson, who were both big fans of The Velvet Underground and hoped to use their fame to boost Lou’s career. At the same time, Bowie witnessed closely just how quickly and easily an artist could shift and adopt whatever persona they chose. It was the start of Bowie’s ever-shifting album personae. Meanwhile, Lou created an entire album about gender, identity, transvestitism, and drug abuse. One of the album’s most explicit songs, “Walk On The Wild Side” somehow became a radio hit.

The logical progression for an artist who has found a lane that resonates with audiences and critics alike would be to follow that path further. “If it ain’t broke” and whatnot… Lou Reed went a different direction. He followed Transformer up with a concept album about violent drug addicts in the end-stage of a miserable marriage. Reed initially planned it to be a double album, complete with photo book inserts of the married couple in all their squalor and misery. Reed was at the time witnessing his own marriage to his first wife crumble amid his growing addiction and violent outbursts, and most of it made its way into the album. Reed even managed to use some of his wife’s most painful family stories, and he turned the fictionalized versions of her family completely monstrous and amoral. Long after she allowed Lou close enough to hit her physically, Berlin stabbed at her over and over.

Frustrated with Reed’s unpredictability, RCA demanded his next album be a live album of his Velvet Underground and solo hits. Rock & Roll Animal is a great live album, but feels exactly like a studio-produced greatest hits collection. Only Lou’s amazing performances make it stand out. The next album, 1974’s Sally Can’t Dance was his “wave the middle finger high” salute to everyone. It’s a punk blueprint, with a drugged-to-the-gills Lou writing and singing a “fuck you” to just about everybody: haters, imitators, label executives, and “just the hits”-loving audiences alike. RCA rushed a second live album out, using the rest of the songs from the live Rock & Roll Animal concert.

Disgusted with RCA, Lou decided he wouldn’t even try on his fifth album. Metal Machine Music was – very literally – nothing but feedback. Lou placed monitors and speakers in a room with microphones in between and let them run. And he demanded that it be released as a double album, as Berlin had been intended. He even did a press tour for the album, lying and claiming the album was the result of a painstaking digital process and loaded with deep meanings, sort of an aural abstract expressionism. In reality, the entire effort took him about two hours and almost no effort. Audiences and critics alike turned on Lou. The consequences of presenting an expensive double album of nothing but feedback and monitor buzzing was too much for most people, and Lou Reed was effectively “consequenced”. Album sales dropped off. Concerts were suspended. Magazines refused to write about him.

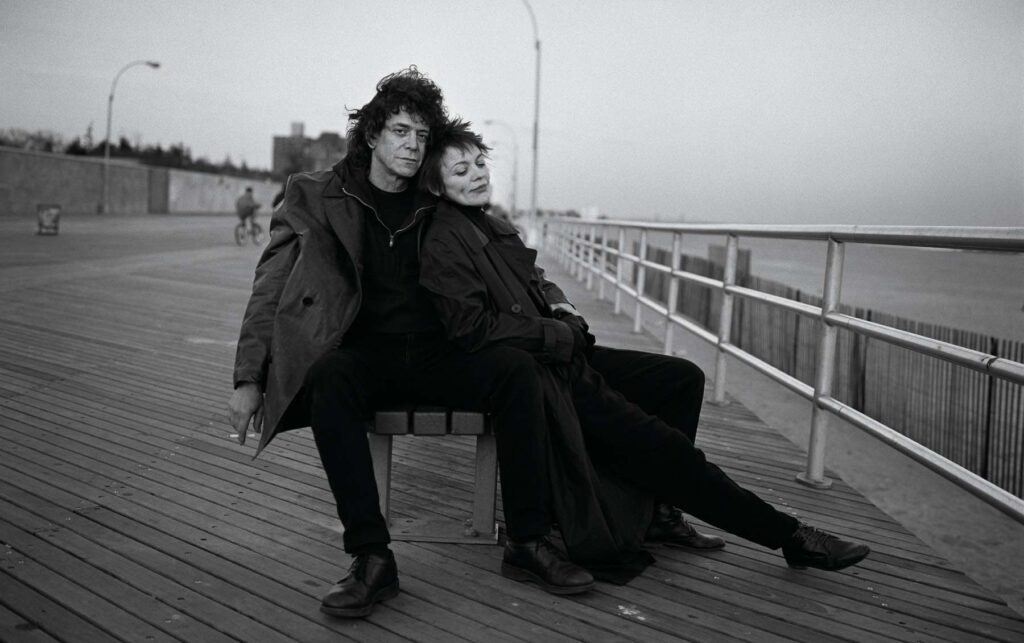

So he recorded a soft rock album of love songs. Coney Island Baby. There is no tongue-in-cheek cynicism anywhere on the album, either. Reed was genuinely in love with Rachel Humphreys, a transgendered woman with whom he would live for the next four years. Coney Island Baby was Reed’s love letter to her, to love, and to New York. (He even mentions his old elementary school on the album.) Rock critic Roy Erdoso summed Lou and the album up perfectly when he wrote, “who else would have had the nerve to try to find ‘the glory of love’ in the reveries of a troubled would-be high-school football player (in doo-wop style, no less)?”

This is the fundamental difference between Lou Reed and the panicky “cancel culture” heralds of today. To Reed, consequences were just part of the deal when creating the art you wanted to create. By being true to yourself, it meant fewer album sales. It meant being bypassed by popular culture. It meant ridicule and financial instability. It meant solitude and misunderstanding. It’s a lonely place to be, but it certainly beats creating art you’re not proud of, or don’t enjoy. There are wealthy teen pop stars who will never have the opportunity to experience a committed artistic experience or creative control. And while that life has its rewards, Reed was never afraid of the consequences of a fulfilling life.

And it’s important to note that numerous moments in Reed’s career would get him “canceled” today. 1978’s “I Wanna Be Black” is a strange mixture of corny jokes, vocal outsiderism, and transgressive trolling wrapped up in a very stereotypically racist set of lyrics. It likely wouldn’t get released today, and even a draft version of it would bring swift consequences. The difference? It wouldn’t matter to Lou Reed. Because the belief that art, politics, or philosophy should be both transgressive, challenging, and universally accepted is a child’s fantasy of the world. Comedian Bill Burr commented this week that “these are crazy times” because of a castmate’s recent “canceling”. Her “cancelation” was to be released from an acting job after being warned six times by the parent network to stop publicly making divisive political comments. She received a movie offer in response to the firing within 24 hours.

These are not crazy times. This life has always had consequences. The great artists Lou Reed start at that reality and work fearlessly within it.