SAM COOKE: January 22, 1931 – December 11, 1964

If there’s a common description about me, it’s that I’m very easy to get along with but difficult to truly know. I can be a different person depending on the company I keep. Some people can know me for years, possibly even consider me a friend, and not know much about me. Not surprisingly, I’m more open in exercises like this or on stage than I am when I’m face-to-face with people, even those closest to me. When I sing or when I write, I’m trying to express myself openly and accurately without concern for how it might be taken, or edited for the benefit of the audience. After 15 years of marriage, I’m still better at communicating with my wife through email than in a verbal discussion. Because of this distance that I cultivate, it’s difficult for people to trust me and to get truly close to me. For most people, that’s fine. They enjoy my company, they appreciate the time we spend and while I may not be vulnerable or compassionate enough for a deep relationship, I’m usually pretty fun to hang out with. It’s those closest to me who seem to regularly struggle with understanding me. It’s those who care the most who also live in fear of what might happen next; not because I’m volatile or explosive, but there’s an unpredictability to a person like me. And as difficult as it must be to care about someone unpredictable, I assure you it’s no easier to be the unpredictable person. To others, it feels like I hide secrets and dreams, and every example of my unpredictable nature is proof of a secret trying to burst through my emotional armor. The truth, however, is usually less linear. Most of what keeps me silent is an inability to know – or believe – that what I’m thinking or feeling has merit. That it’s accurate. That it’s even worth sharing. And so my unpredictable responses rarely are the result of a secret desire escaping from the vault within my soul. Usually, it is simply the lashing out of an emotional mute. A behavior not designed to send a specific message, but to blow off steam from the pressure of never trusting myself. People believe my actions to stem from a place I’m not willing to share; in truth, they usually come from the hollow place where I know something should be, I just don’t know how to fill it.

I recognize this isn’t a great way to live my life. I recognize that it’s a barrier to healthy relationships. And I also know that I’m not the only person who acts this way. In fact, I recognize others who behave this way, and often find myself attracted to them for one reason or another. Which is probably why I fell so in love with the singing voice of Sam Cooke. How I felt like I understood every strange nuance to his voice. And why it didn’t really surprise me to find out that his life had been plagued with inexplicable moments, or that he had died from a bullet wound while he was drunk and half-naked at a $3 motel. To people who aren’t sure how to engage with the world, life can feel antagonistic, and conflicts often feel terminal. For them to turn literally terminal isn’t even that shocking.

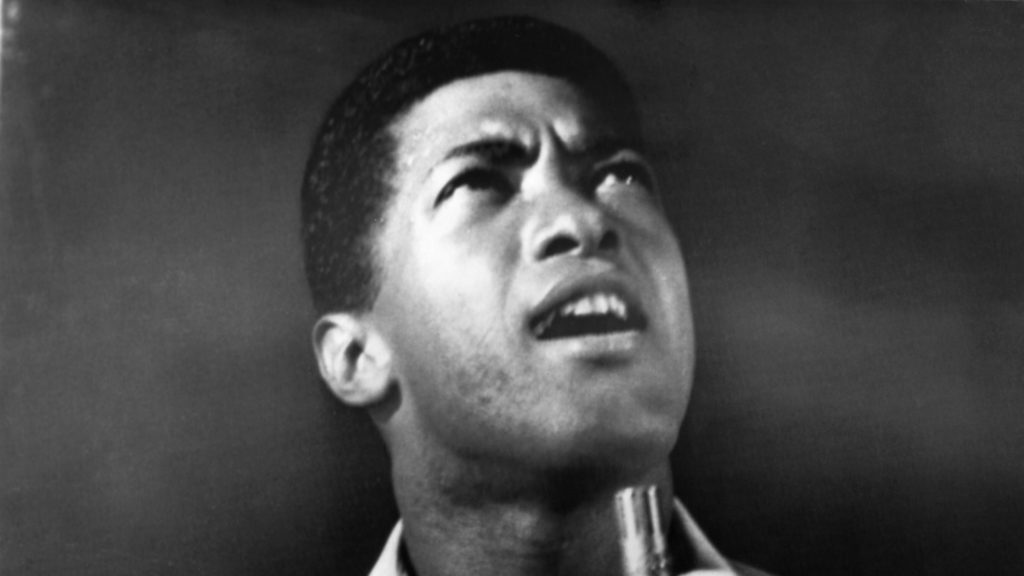

Sam Cooke was one of a few artists who successfully made the crossover from the sacred to the secular. Growing up in the church (he was the son of a pastor) and singing with the gospel group The Soul Stirrers, Cooke achieved fast fame for his voice. It was an incomparable voice, effortlessly shifting from tenor to countertenor to falsetto, often times within a few bars. His voice could shift from silk-smooth to gravel-rough, depending on the syllable he wanted to accent. And his phrasing was equally as fluid: Cooke could stop and start sounds with a metronomic precision, or he could move like a jazz riff, entering early, leaving late, holding on to the note just long enough to give it a lot of tension, but never – never – enough to break the mood. If ever a singer was truly all-encompassing, it was Sam Cooke. He was everything to every song, and despite being the youngest member of The Soul Stirrers by nearly a decade, Cooke immediately became its star. Every song became his song, because all of the vocal techniques were unique. These were not trained techniques; Cooke was never formally schooled as a singer. These were just Sam Cooke’s methods for communicating, and the rawness and the depth of that communication drew people in. They liked The Soul Stirrers, but they felt they knew Sam Cooke.

The problem is, nobody knew Sam Cooke. Even Sam Cooke didn’t know Sam Cooke. It’s a trite (but common) analysis to say that Sam Cooke’s problems stemmed from the fact that he denied the sacred music of the church for the secular music and its carnal lifestyle. But Cooke was a man of contradictions. There is no way to listen to his gospel songs and not feel the passion of the true believer that Cooke feels for his faith and his religion. Yet, in the midst of The Soul Stirrers popularity, Cooke was juggling two pregnant girlfriends in Chicago and another pregnant girlfriend in Cleveland. And those are just the pregnant girlfriends, whom we know about because of court records. By all accounts, Cooke enjoyed the money and fame of The Soul Stirrers, unashamedly: fine clothes, expensive cars, and endless opportunities for sex. If we don’t know much about Cooke’s inner conflicts of this time, I don’t believe it’s because Cooke was guarded and kept his secrets hidden. It’s quite possible that Sam himself didn’t know much about his inner conflicts. He liked fine things and casual sex. He liked gospel music and he loved the Lord. And any contradiction that those things provided may have felt too overwhelming to deal with, too complex to resolve, and the parties he might defer to for guidance and direction were too black-and-white in their interpretation. And so Sam lived in the world of the unknown, which settles the internal spirit but makes connections with the outside world seem hostile and antagonistic. Cooke regularly fought with Cadillac-driving, expensively-dressed preachers who called him out for his indulgence. He lashed back in defense of his faith at people who cited his excessive libido as proof of a lapse in belief. And when people would criticize the sexiness in his singing voice within a gospel song, Cooke kept right on singing, as smooth and sexy as before. And his behavior in these moments could careen wildly between rational debate, passive-aggressive ranting, and bullying.

His entire career would be driven by these kind of antagonisms, with Cooke regularly finding footing with one point of view and then shifting dramatically when a new direction presented itself. Cooke bounced back and forth between the benefits (and the strictures) of faith. He bounced back and forth on issues of art. And commerce. And race. He was a gospel singer who sang like an r&b singer until he met r&b producer Bumps Blackwell, and then he was an r&b singer who sang like a gospel singer. With Blackwell, he actively courted an African-American audience by singing r&b that sounded “white”. Cooke found quick success with sanitized Pat Boone-worthy hits like “Cupid” that failed to showcase his many vocal skills and limited him, emotionally. He would later meet a white manager, Jess Rand, and leave Blackwell so he could actively court a white audience by trying to sound “blacker”. As he courted an increasingly politicized and empowered African-American audience, he became more and more neutral on the subject of race. When Jess Rand encouraged him to adopt an attitude more aligned with the growing self-empowerment of African-Americans, Cooke refused. Rand ghost-wrote a letter – pretending to be Cooke – that was later turned into an article, and portrayed Cooke as a strong, independent man who would never take a job he found personally degrading or demeaning. Which was true; Cooke had refused to play segregated shows for his entire career. Cooke fired Rand, anyway. Cooke would wholeheartedly embrace each of these career steps (and mis-steps), right up until a contrary position presented itself. Then Cooke would do something irrational and either cut the new option out of his life completely, or jumped on board with the new option and burned the old option to the ground.

All of this ignores the fact that Sam was constantly testing people. He’d book Blackwell and himself into expensive, segregated hotels. Sometimes they would both be turned away, sometimes just Blackwell. Either way, Blackwell was almost always humiliated. He would make Jess Rand stay in frightening low-rent motels in Harlem while Sam would stay in a luxury suite downtown. Rand would get calls in the middle of the night, asking him to brave the unsafe Harlem streets to come to Cooke’s hotel, solely to bear witness to Sam in bed with multiple women. And these tests and these regular feelings of antagonism would plague Cooke throughout his entire life. And his reactions would regularly be unpredictable. On December 10, 1964, Cooke introduced himself to a beautiful woman at the bar at Martoni’s, a popular entertainment restaurant in Los Angeles. Whether Sam Cooke knew that the beautiful woman was commonly the escort of many of Los Angeles’s most famous men is unknown. Whether or not she was a prostitute was unknown (though she was arrested for prostitution less than a month later). But she left the bar with Cooke, and instead of driving to his hotel, Cooke drove them 17 miles to the low-rent Hacienda Motel, whose client demographic was African-American and mostly poor. The woman checked in with Cooke as “Mr. and Mrs. Sam Cooke”, and they went to the room. The woman later claimed that she got to the room and changed her mind about having sex with Cooke. Cooke, drunk and enraged, got physical with her and slapped her. She ran out of the room and across the parking lot. Cooke emerged from the hotel room wearing nothing but a sportcoat and his shoes. He assumed the woman had made her way to the motel office and so he charged to the office door, which was locked for the night. He began to pound on the door and screamed “Where’s the girl???” The motel manager, a 55-year old woman terrified at the site of a naked, enraged man, phoned for the police. Cooke pounded harder, growing angrier and angrier. The manager pulled a pistol and exchanged words with Cooke, which only made him angrier. Cooke kicked through the door and charged the manager, knocking them both to the ground. The manager fired three shots, one which pierced Cooke’s heart. Shocked, he screamed “Lady, you shot me!” and he attacked her again. The manager grabbed a broom and started to beat Cooke until the singer collapsed on the floor, dead.

Throughout this project, I’ve written about many people I admire who have the ability to ignore the critics and the dissenters and follow their own vision to its glory. In a documentary I recently watched about Sam Cooke, a few fellow musicians described him that way. But the evidence doesn’t support that. Sam Cooke may have told people to go to hell, and he may have done things he was advised not to do. But he was always following a path that someone had cleared for him. When people do things we don’t expect, it’s easy to assume there is a grand plan or a hidden intent beneath it. But sometimes, all that lies beneath it is weakness. Or emptiness. Or a need for relief from anxiety and confusion. Grand plans and self-direction are what’s missing, not what’s being hidden. And hollow centers don’t hold, so anything that affects them – however well-intentioned or well-reasoned – can feel reassuring, while any contradiction just creates anxiety that may eventually demand to be released in unpredictable ways. And so it’s not nearly as sordid or confusing why Sam Cooke’s life ended the way it did. Or why his behavior was so unpredictable. Or even why his final words were explanatory – more shocked than terrified. Sam screamed out in recognition of being shot, but clearly didn’t assume he might die. Because when you live life like that – centerless, adrift, hollow – it often feels like it will never end, and it will never change. You can hear it in every note he sings in “A Change Is Gonna Come”; Cooke’s version is only partially hopeful, but mostly it’s just a weary voice clinging to salvation in some unknown, undefined form. For Sam Cooke, it didn’t change until he left this world.

Let us pray that other, similar souls among us get to bear witness to a better end.