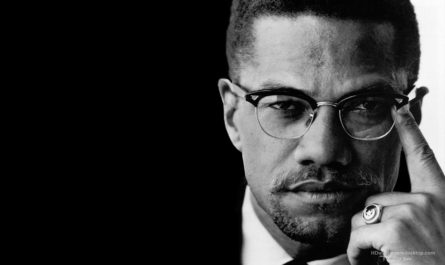

ABBIE HOFFMAN: November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989

If I had heard Abbie Hoffman speak prior to buying the 1990 “Sound Bites From The Counter Culture” album in 1990, I don’t remember it. I certainly knew who he was, and I knew of his place in history as a member of the Chicago 8 and founder of the Yippie movement. And I remember the sad feeling I had when reading about his death the previous year. But when I listened to Abbie’s powerful speech on the nascent “War On Drugs”, I was less interested in learning more about the content (my opinions and Abbie’s were already fairly similar) and more interested in learning about the man, himself. I spent the next couple of years combing libraries and used book stores to find everything Abbie published, and reading every biography on him – positive or negative.

The thing that made Abbie so different from so many of his contemporaries (many of whom became active, powerful members of the very system they rallied against in their youth) was Abbie’s understanding of the need to put a human face on activism.

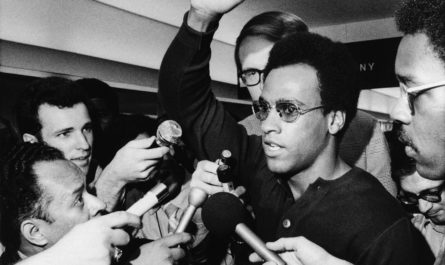

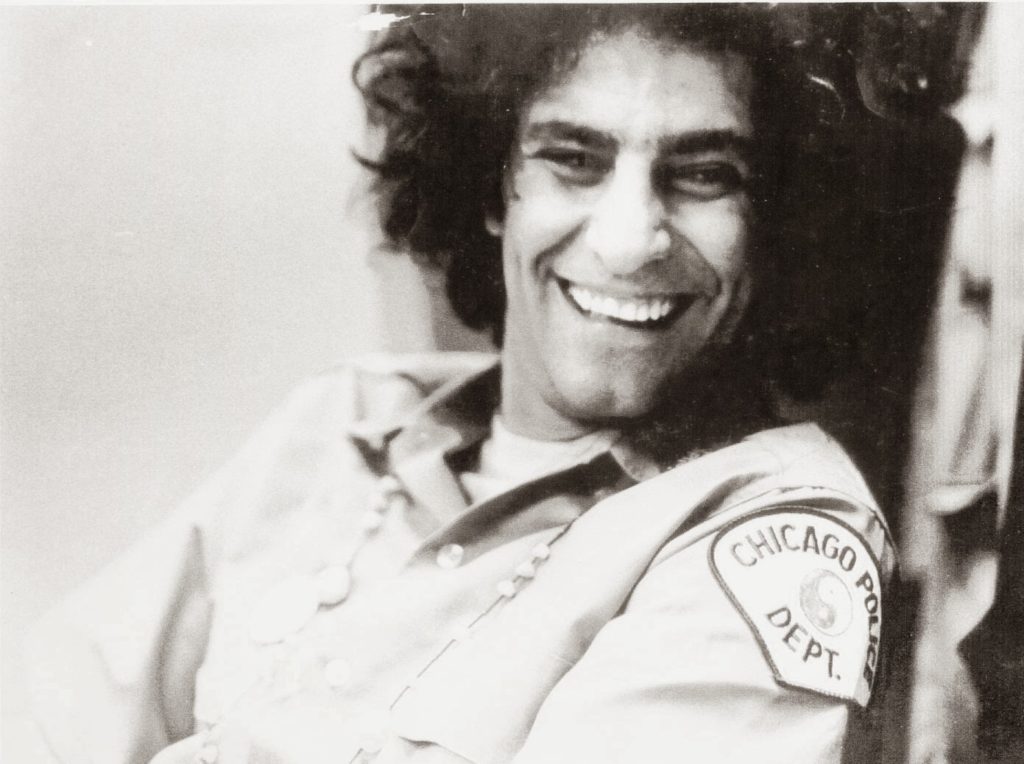

Today, we would refer to Abbie as a “brand”. But in the late 60s, nobody quite knew what to make of him. To many, he was simply the clown prince of anarchy. His battles with the state were legendarily comical. While the SDS and The Weather Underground used the language of revolution and terrorism, Abbie used the language of a slapstick vaudevillian. While others were bombing government offices and universities, Abbie was throwing dollar bills into the trading pit at the New York Stock Exchange or releasing a live duck during an interview with David Susskind. His exchanges with Chicago 8 trial judge Julius Hoffman (no relation) were contemptuous, but always comedic. Abbie was confrontational, but in the way only a court (no pun intended) jester can be. The jester is the only person allowed to criticize the king, because kings needs a voice of reason but only if it can easily be branded a “fool” if the words begin to sting. Abbie was that fool.

A few years into his activism, Abbie went to San Francisco and spent time with The Diggers, a theatre collective who believed in the abolition of commerce and trade. Along with their guerilla theater work, The Diggers created free stores, free medical clinics, and arranged for free “crashpads” through local churches. After learning of the many tricks The Diggers used to avoid paying for the standard “requirements” of life, Abbie returned to New York and incorporated them into the “Survive!” section of his 1971 urban-guerilla manual “Steal This Book”. Diggers co-founder Peter Coyote was appalled. To him, Abbie had taken survival tactics they had assembled to help the poor, put his own face on them, and then shared them with “disaffected kids from Scarsdale”.

What Coyote missed, however, was the power of imprinting that Abbie Hoffman provided. The Diggers and similar groups provided solutions. They were like chefs presenting a fully-cooked meal to hungry people. But Abbie was an example. Abbie not only taught people “how” in his books, he allowed us to see how the creation was made… and he made it entertaining and human enough that we could see ourselves reflected in his actions. When we saw Abbie completely disrupt court proceedings simply by refusing to stand upon the judge’s entrance, we not only understood the shaky, hollow foundation decorum upon which so much of our American power structure But it was also the action of a naughty schoolboy – an action any person could envision themselves doing. That was Abbie’s power. He allowed us to see ourselves as agents of change, instead of being subjects to it. People were already subjects of the state, in Abbie’s mind; making them subjects to the sweeping tides of change was just as unreasonable. The more I studied Abbie’s life and example, the more I realized that being the change I wanted to see in the world (to paraphrase Gandhi) was always Abbie’s intent. He never wanted to deliver a better world to us, he wanted us to embrace our power and become that better world.

When Abbie’s body was autopsied in April of 1989, coroners found a massive amount of phenobarbital and liquor in his system. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder a decade before, Abbie had allegedly self-medicated to deal with his excessive mood swings. Many people have speculated on the origins of his bipolar disorder; was it merely an inherited chemical imbalance, a neurological fluke, or had it been caused by more than two decades of extreme highs and lows (both public and private)? Whatever the origin was, Abbie Hoffman was a single man fighting ideas. Fighting preconceptions and biases. Fighting the lesser demons of our collective soul. But the fact is, those demons have no face, no body. And if they exist in one of us, they exist. Battles with ideas are matters of perspective and size and scope, but they lack true definition. And eventually, fighting a monster that refuses to die eventually wears down the soul. Some fighters gave up the fight and joined the system with the misguided belief that they could change it from within (Hayden, Rubin). Others burned themselves out without ever knowing how or if they made a difference. Still others fought their entire lives in anonymity. But Abbie inspired millions to do something – anything – and by doing so, changing the world.