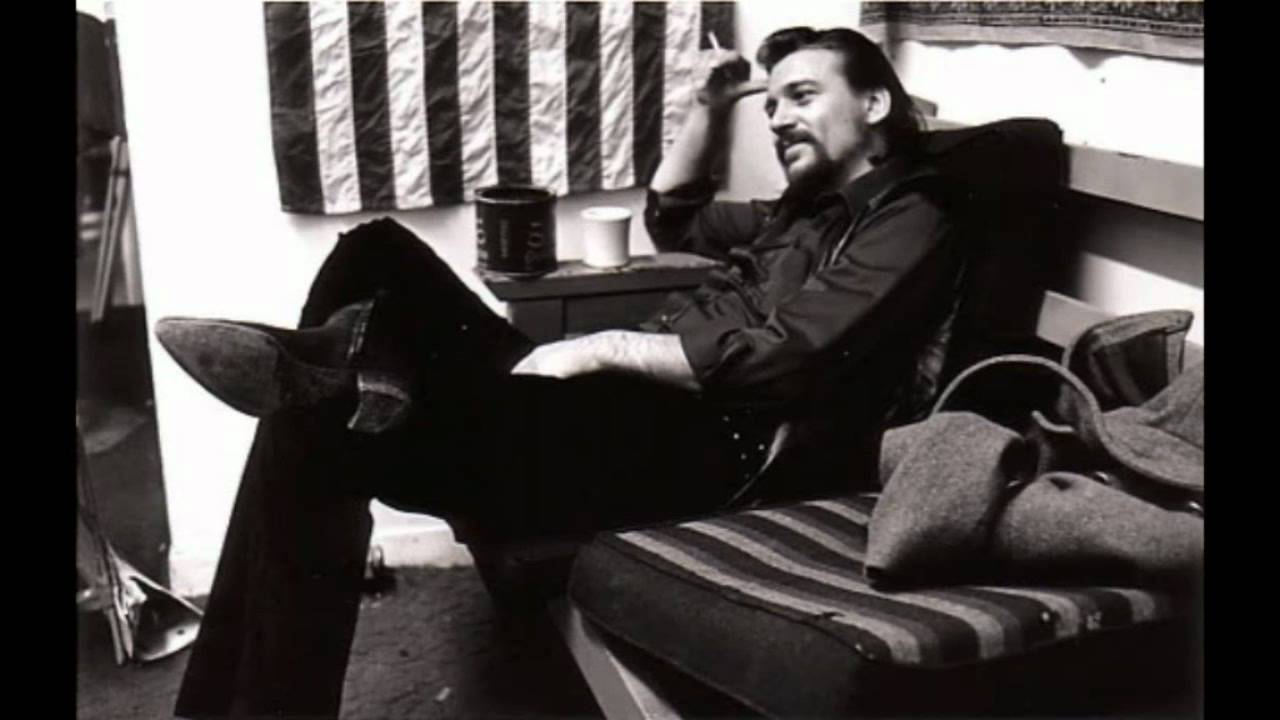

WAYLON JENNINGS: June 15, 1937 – February 13, 2002

I’m at an interesting crossroads of my career. For most of my adult life, I’ve worked with a fear-based intensity, like a man trying to outrun a fire. My consistent belief was that termination was always nipping at my heels, and the only way to outpace it was to outwork everyone else. “I may not be the best,” I believed, “but nobody is going to work harder than me.” And so I spent years getting paid for 40 hours of work, but working 70, 80, 100 hours in a week. Even as I piled up “Exceeds Expectations” annual reviews and outpaced co-workers on merit increases, I was sure that one slip-up would be the end of me. It was a co-dependent nightmare, but with an unexpected result. If you’ve read Malcolm Gladwell’s writings on expertise as a by-product of 10,000 hours of practice, all of those hundreds of hours of extra work and all the all-nighters added up to a level of expertise beyond what a typical colleague would have achieved at this time. In recent months, I’ve published a book, written a couple of popular industry articles, traveled overseas to present at industry conference, scheduled three more conference presentations and a webinar for this year. Sharing my knowledge and helping others use that knowledge to craft strategies is the work I want to do – the work I’ve always wanted to do. And yet, my co-workers are accustomed to having a ceaseless workhorse to bail them out, so we’re in a state of conflict. (In fact, one of my primary peers resigned over the holiday break. Instead of hiring a replacement, they simply assigned his full-time workload over to me.) So, how do you switch to the career you want when others are trying to force you into a box in which you’d be capable, yet uninspired? I’m at a crossroads, and I’m often left feeling lonesome, ornery, and mean. Which is why I keep looking to Waylon Jennings.

I barely remember a time when I didn’t like Waylon Jennings. I was eight when I heard my first Waylon Jennings album and was mesmerized by his image (with Willie Nelson) on the album cover. He was the voice of “The Dukes of Hazzard”. I was unaware in the 1970s that Waylon had a unique sound. I was too young to know the history of Nashville and its trends, and was unaware that this new look and new sound – labeled “Outlaw Country”, because it was so contrary to the Nashville style of the times – was something unique. I just knew that Waylon Jennings felt like he was telling the truth in the way few other singer could. I was used to country music that was sad and remorseful. Singers drank and ruined their lives and felt bad about it; Waylon’s songs may have been penitent, but they were never apologetic. In a Waylon Jennings song, the biggest losers may have been sad or depressed, but never ashamed. Waylon Jennings songs were about people who did bad things, but never about bad people. Even his outlaws were men who did bad things, as opposed to bad men. And all of them were not only worthy of love, but actively and regularly loved. It was a unique delivery that I connected with as a child, and grew to understand more and more as I grew older. Because it wasn’t simply a vocal style or a choice of lyrics; it was a representation of who Waylon was.

Waylon Jennings’s relationship with Nashville is as unlikely as it is inspiring. Waylon left school at age 14, alternately picking cotton and working radio DJ jobs around Texas until he settles in Lubbock, Texas at age 17 were he befriended a fellow DJ named Buddy Holly. Buddy would soon skyrocket to fame, but he and Waylon remained good friends. Buddy encouraged Waylon, and produced his first record. Waylon eventually joined Buddy Holly’s touring band on bass guitar, and played with his friend for a year until Holly’s untimely death in 1959. Jennings would grieve in Lubbock, and eventually move to Phoenix to begin crafting a sound somewhere between honkytonk and rockabilly. In the early 60s, he tried to find success in Los Angeles, but record executives tried to force him to lay more pop-oriented music. Waylon refused and moved to Nashville in the late 60s. But Nashville in the late 60s was a place of multiple (often conflicting) identities. On the one hand, polished “countrypolitan” musicians like Eddy Arnold and Glen Campbell were popular. But the Bakersfield sound of Merle Haggard and Buck Owens was also gaining popularity, and Loretta Lynn and Johnny Cash’s “At Folsom Prison” was bring country blues back into popularity. So when Waylon arrived in Nashville there were many opportunities, but even more directions. And stipulations. And marketing plans. Waylon had earned his chops in fifteen years of playing rock shows and honkytonks, in failed attempts and in personal losses. And he knew that he only wanted to follow his own muse, which guided him towards total honesty, edgy compositions, and muscular arrangements. That was Waylon Jennings, and losing any of those elements to try to gain fans or sell records wasn’t something he was interested in. Sure, there were plenty of music label offers, but each one was a request to force himself into a different type of market-driven box. Finding no option that was palatable, he chose the least-restrictive offer, signed with RCA Records, and spent the next five years fighting their system.

RCA at the time had a marketing machine that could have turned Waylon’s forceful baritone and beautiful Telecaster into a hit-maker. But instead, Waylon went head to head against the system. He ignored the songwriters they recommended, focusing instead on working with great songwriters like Kris Kristofferson, Billy Joe Shaver, and Hoyt Axton, and Alex Harvey. He eschewed directions to make his style more pop-oriented and began to craft a more muscular, edgy sound with Nashville session musicians who preferred the rawer, honkytonk licks he preferred. His efforts turned out a few minor hits, and earned Waylon a reputation as a troublemaking under-achiever. Eventually, he would use that potential and that frustration to re-negotiate his contract with RCA. He would take less money upfront in exchange for artistic control of his albums. RCA agreed, assuming it would eventually be a way to rid themselves of the headaches, and possibly rid themselves of Jennings himself. Instead, Jennings embarked on a decade of hits. The sound that L.A. and Nashville had tried to modify turned out to be wildly popular, mostly because of its honesty. Waylon was branded a leader of the “outlaw country” movement, named for Jennings’ refusal to play by normal rules. (Willie Nelson was also a founder of that movement, as he inexplicably cultivated a massive career from outside Austin, Texas, then a rural outpost with only a small local music scene.) Not only did the outlaw country movement prove to be popular with country music fans, Waylon became a cross-over hit-maker, scoring more than a dozen top ten hits and as many gold albums in a decade. The record labels had been unable to foresee this success because they had never seen anything like it. Waylon Jennings was unique, and only one person could advocate for the value of someone unique: Waylon Jennings, himself.

Soon after winning his battle to re-negotiate his RCA contract, Waylon was hobbled by hepatitis and amphetamine addiction. Looking to extend his audience, Waylon booked a six-night engagement at Max’s Kansas City, a legendary New York City rock club. Nobody – nobody – recommended that decision. Country artists didn’t play New York, much less one of the premier rock clubs. In 1973, Max’s was the stomping grounds of Bruce Springsteen, The Ramones, Iggy & The Stooges, even a young Hall & Oates. Waylon kicked off the tour with his typical honesty. Before the first song played, he told the notoriously disaffected New York audience, “I play country music. We hope you like it. If you do, I want you to tell everybody you know how much you like it.” It was a humble beginning. And then, the honest coda: “If you don’t like it, don’t say anything mean about it, because if you ever come to Nashville, we’ll kick your ass.” Waylon kicked off the six night run with a threat. It was pure Waylon honesty, from the first moment. And he was right again; the New Yorkers adored him.

There’s a purity in staying completely honest to your own vision. It’s something unfamiliar to most of us, who feel fragmented and often times in conflict between our dreams and our reality. And fighting for what we want often feels too frightening to risk. It’s those moments that we need to look to Waylon Jennings. To recognize that the life you want to live is a unique life, and you’re truly the best person to judge how to direct it. To recognize that the struggle to live the way you want is very real, and very tiring. It’s a life you’ll have to fight for, long and hard. But in the end, Waylon knew he was living the life he wanted, despite the feedback. Despite the criticism. Despite all of the opposition, Waylon was a man without conflict, and that shined through in his art. It made him irresistible. Unsullied by compromise and imbued with the light of doing exactly what he believed he was put on this earth to do, Waylon Jennings gifted the world more than just some drinking songs. He showed us how to be honest to ourselves and faithful to our internal compass, and how much that affects everyone around us. Even in the ugliest moments, it’s impossible not to love that honesty. As crazy as it may seem at times, it’s what will keep us from going insane.