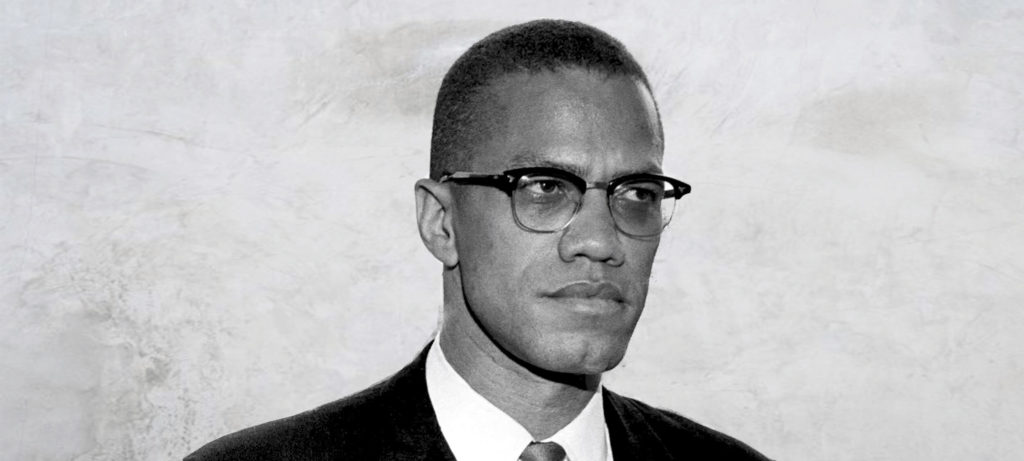

MALCOLM X / EL-HAJJ MALIK EL-SHABAZZ: May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965

I have made a lot of changes in my life in recent years. There is still plenty of opportunity for me to improve my life, but I’ve done a fairly decent job of making some improvements. And so it catches me by surprise when old patterns arise and around me, and I find myself slipping into patterns I thought I had eradicated. Something happens at work or something happens at home that re-ignites old patterns without my awareness, and suddenly I’m thinking in ways I’m not aware of, and behaving in ways I thought I had eradicated. Change is frustrating, because we never truly now when we have truly evolved into a different state of being, or if our new behaviors are just a temporary, untested state. We want to believe that we’re a different person, and it’s a slap in the face to find out that we were just different because we hadn’t been tested. My high school football coach used to say, “In times of stress, men revert to their original form.” I’ve experienced that recently. Changes I was sure I’d made for the better turned out to be fairly shallow and untested changes. As soon as I ran into some triggering stressors, I reverted right back to the way I used to be. It’s difficult to change our beliefs and behaviors. Hell, it’s hard to stop smoking or to lose ten pounds. And so when I see someone who can fundamentally change themselves, I have to take notice. When they fundamentally change themselves twice, it’s almost miraculous. The fact that one of the most politically divisive figures of the 20th century was one of the few to be able to accomplish this makes it even more interesting.

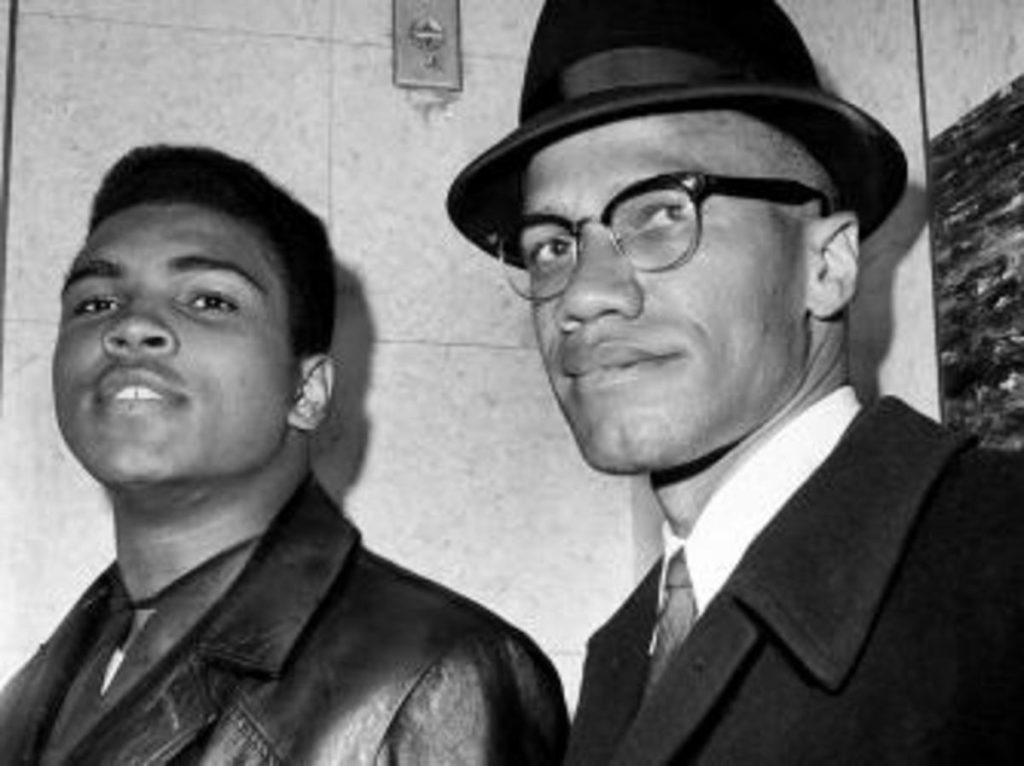

Malcolm X was not born into a charmed life, but if he had one saving grace, it was being the son of Earl and Louise Little. Despite being raised in a time of deeply-entrenched Midwestern racism, Earl Little Earl was a Baptist minister and student of Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African teachings, most notably Garvey’s belief in black self-reliance. Earl Little became a leader of the local Lansing, MI Universal Negro Improvement Association, and strongly instilled the belief in this children that African-Americans could – and should – be self-reliant, away from typical white society. It was a lesson that young Malcolm Little was beginning to understand when his father was killed by a streetcar in either an accident or a murder by white racists. Louise would eventually suffer a breakdown, and Malcolm would spend six teenage years shuffling between family homes and foster homes before turning to a life of crime. He’d been an intelligent young boy with strong aspirations instilled by his parents, yet he met rejection and ridicule at every step in school. There are few things as dangerous as being smart, under-utilized, and resentful, and so Malcolm would spend his time off as a Pullman porter on the trains between Boston and New York to rob wealthy Boston homes. He was caught at age 21 and sentenced to eight years in Charlestown penitentiary. It was here that Malcolm Little became Malcolm X.

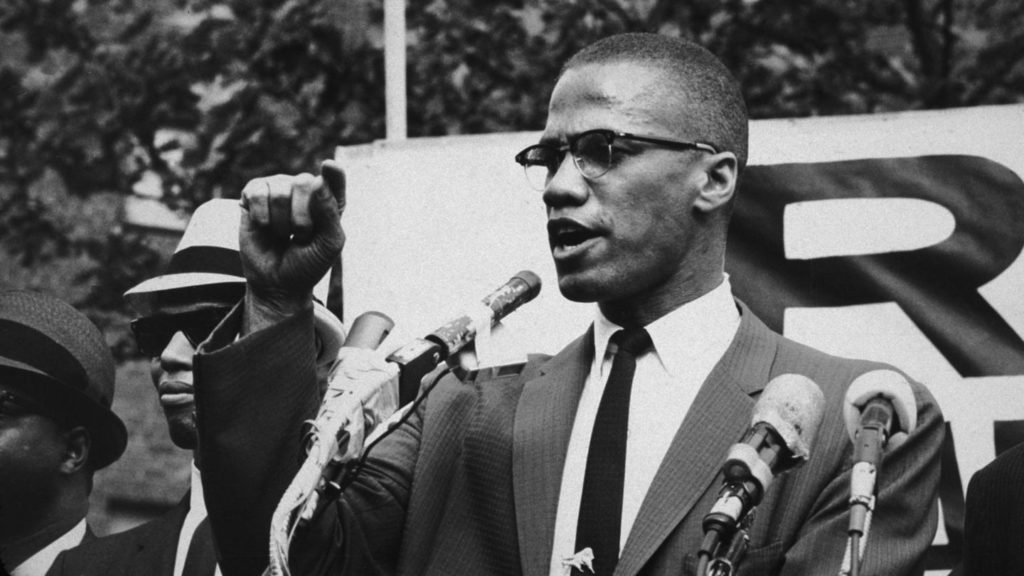

drugs. He changed his diet. He swore off sexual relationships with white women. But these are abeyances; these changes can be enacted with simple willpower. The real change was in his personal beliefs. To become Malcolm X. Malcolm Little had to change his belief in his own worth – as a man and as an American. To become Malcolm X, he needed to lose all of the self-doubts and limiting beliefs that had been ingrained into him for over two decades. Now, instead of believing that he was fundamentally incapable of achievement because of the color of his skin, he believed that the only limitations he faced were systemic and societal beliefs. And instead of accepting these beliefs or looking for a way to circumvent them, he confronted them head-on. The change from Malcolm Little to Malcolm X was striking because most people change their lives to make life easier and more peaceful. While losing the societal stigma that held Malcolm Little down must have felt like spiritual freedom, the resulting backlash was severe. Because confronting the power structures which oppressed Malcolm Little had turned Malcolm X into an enemy of America. And Malcolm X accepted the role, through hate mail and government opposition and hate speech and assassination attempts. When people are trying to kill you for your beliefs, it would be easy (and excusable) to shift back into previous behaviors. It would have been forgivable for Malcolm X to go back to being Malcolm Little and taking a job on the train cars again. Forgivable, that is, to everyone but Malcolm X. Malcolm Little had changed, and no amount of stress or pressure was going to allow his to revert to his original form.

Which makes Malcolm X’s transformation after his pilgrimage to Mecca so astounding. Malcolm X evolved from Malcolm Little in a brief period, and then spent years as Malcolm X – tested and tried, physically and spiritually. And when he finally made his pilgrimage, he was forced to reconsider many of his beliefs. It was here that Malcolm X evolved into el-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, a nuanced response to the rigidity and limitations he found within the Nation of Islam. Many of the beliefs that had helped him evolve into Malcolm X were still active, but the change was much more complex. Because the evolution from Malcolm Little to Malcolm X was a near-complete rejection of the limiting beliefs that Malcolm Little had lived under. This evolution was the rejection of some of his beliefs, but not all. More confusing, some of the beliefs he would reject around the time of his pilgrimage were beliefs that had aided in his evolution to Malcolm X. el-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz was true evolution – a product of natural selection of the spirit. Bad or limiting ideas continually fell by the wayside to ensure that he thrived. And it is no coincidence that as el-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz’s thinking became more mature, more focused, and more nuanced, it also became more threatening. It lacked the black-and-white fundamentalism of Malcolm X’s pre-pilgrimage days, which not only indicted the racist systems of America, it also alienated former followers who strongly believed in the easy answers provided by fundamentalist rhetoric. Unsurprisingly, el-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz evolved to a state that made peace – among Americans, but also within himself – seem possible. And that made him dangerous – too dangerous to live. And el-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz knew it. He had been threatened too many times and warned too many times that to think that the threats were idle. And yet he continued forward until his assassination on this day in 1965 at the Audobon Ballroom. Why? Because he had truly changed.

As most of us soldier through our own lives, we’re regularly presented with the contrast between who we are and who we want to be. We remain abundantly aware of all of the goals left incomplete and the dreams left unattended. We live our lives as lesser versions of ourselves. Even if we try to change, we often times revert to old patterns and old behaviors. This pattern is so common, it’s easy to believe that change isn’t possible. Or necessary. Or even wise. We’re settled into our patterns, no matter how much they limit us or how unfulfilled they leave us. We wear them like old clothes, and changing out of them becomes really difficult. Change occurs when we truly resolve the issues in our lives that make our limiting beliefs feel comfortable, when we bravely face the habits and patterns and traumas of our past and genuinely resolve them, so there is no old state to return to. Change happens when we destroy the old ”me”, which is dangerous. People who liked “the old you” will lobby for your return and/or condemn the “new you”. Because change is not just difficult for the person ding the changing; it alters every ecosystem in which the person lives. But the truth is, change is a battle between a comfortable now and a better future, and those who can change are able to reap the benefits. It’s an uphill battle, and it requires a lot of work, but it can be done. If el-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz is an indication, it can be done over and over, if we’re ust courageous enough to keep working at it.