I had the chance to speak to Shooter Jennings in the minutes before his September 6 show at Newport, Kentucky’s Southgate Revival House. I complimented him on a recent Facebook post in which he described his father’s openness to any musical style. As a lifelong fan of Waylon Jennings, I mentioned how much I loved the story of Waylon driving around Nashville blasting Primus’ Pork Soda album from the tape deck of his black Jaguar. Shooter said, “I don’t normally put stuff like that out there, but everyone seems to think about my dad one specific way, and that’s not how he was.”

From one generation to the next, that comment was the most prescient statement of the night.

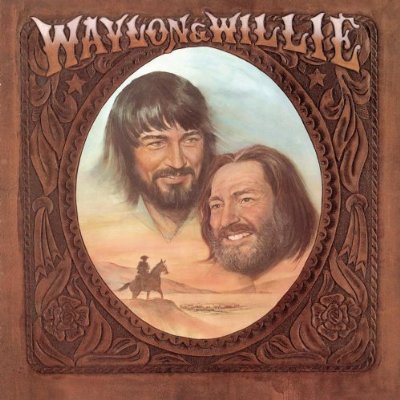

I remember the first time I ever heard and saw Waylon Jennings. My family had moved from the St. Louis suburbs to Detroit in 1977, and in the summer of ’78 we had gone back to St. Louis to visit old friends. In the middle of a large party of my parent’s friends and their kids, the host turned off the 70’s adult-contemporary radio music and put on a country album. I remember the boos and hearty laughter from the dance floor (back patio) at the abrupt shift in musical styles. Sometime after the dance floor cleared, I walked inside to see what it was that everyone was reacting so strongly to. Next to the turntable lay the album cover: Waylon & Willie. With its embossed leather frame around an oil portrait of Waylon and Willie smiling in the sky above a silhouetted cowboy on horseback, alone in the desert.

The song that was playing was “Lookin’ For A Feeling”, and I tried to guess which of the men on the cover was singing. Years later, I would find out that I had guessed correctly, which is odd, because both men were unlike anything I was used to seeing. Outside, my parents and their friends were the epitome of ’70s suburbia. They were young, college-educated. They had children when they were young and got white-collar jobs and were in the early stages of ladder-climbing. They were clean-cut and fresh-faced and ready to take on the world.

But these two on the album cover had long, shaggy hair and beards. I had an uncle by marriage who had long hair when he was a student at Kent State during the Viet Nam era. It was before I knew him well, and I don’t remember ever seeing it, but my family always talked about it with a good-natured chuckle, as if it had been a silly side-story to an otherwise inexplicable time. And I’d seen men with full beards, but they were *men*. In 1978, corporate America kept men’s faces clean. My father, as salesman for Campbell’s soup, was limited in how long he could grow his sideburns – facial hair was out of the question, entirely. All of his friends were clean-cut; full beards were for bikers and construction workers and oil rig drillers. So how could a man have a voice so deep and rich and have a roughneck’s beard, but sing so tenderly of a lost love and have a shaggy, gypsy ‘do? How could someone so modern and free-wheeling be packaged on an album cover that looked like a fancy holster rig that belonged on Doc Holliday’s hip?

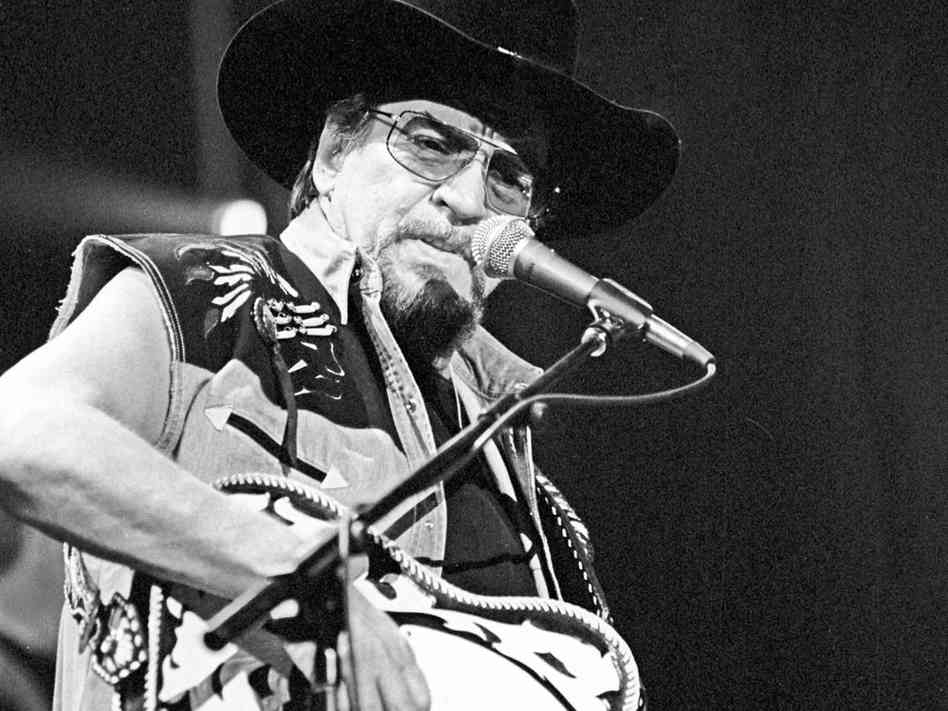

It was that first impression of Waylon that stuck with me for the rest of my life. Waylon didn’t just break rules. Any simpleton can break a rule. Waylon seemed to exist on a plain where the rules didn’t even exist. As if none of them made sense to him, so he just did whatever he wanted, because none of the rules laid out before him made any sense, anyway. In an interview later in life, he said of the music industry, “They wouldn’t let you do anything. You had to dress a certain way. You had to do everything a certain way. They kept trying to destroy me. I just went about my business and did things my way.”

What must it take to think that way? To inherently and fearlessly know that your decisions are right, despite an entire industry contradicting you and pushing at you? How many people have the strength to fight that? How many times do you need to be told you’re wrong or crazy before you eventually start to question your own sanity? How many people just fold their hand and follow the path of least resistance? Not Waylon. He wrote songs for years about how “being crazy” had served him well, and so he kept doing what he felt was right. Damn the torpedoes. And we loved him for it. And we bought his albums. And we reminded him, in the face of it, that we also knew he wasn’t wrong; he was speaking to us with an honesty few had. Hell, yes, he was crazy, but so was the whole world – especially the fools trying to corral him and his career. And Waylon was just crazy enough to speak to all of us. And we loved him for it.

I saw Waylon play at least a half-dozen times over the years, but one of the most memorable solo performances was at The Cubby Bear in Chicago in ’91. The Cubby Bear is across the street from Wrigley Field, an area generally reserved for frat-boy types who wear baseball caps year-round and drink shitty beer because it reminds them of their glory days in the Phi Delt house. The Cubby Bear was a mid-sized club, which held maybe 1000 people, tops. I got there early, and drank beer and watched the people who showed up. I assumed the club would be filled with shitkickers and rednecks and beer-drinking rowdies. And they did show up. But so did the steelworkers from Gary. And the soccer moms from Downer’s Grove. And the frat boys from the next bar over. And the blues fans from Humboldt Park. And the horse farmers from Wauconda. It seemed like every type of person was there. Because Waylon – just by being Waylon – had something for all of us. Some may have thought it was the voice. Some may have thought it was the look. Some may have thought it was the “outlaw” behavior. In reality, it was the honesty. The purity of Waylon being Waylon. Despite the slings and arrows, Waylon always gave us Waylon. Never pre-packaged or focus-grouped or edited. He was always just Waylon. Whatever little elements about him we loved (the voice, the songwriting, the Telecaster, the self-destruction, the hot wife) were just rays of light that emanated from that honesty. We saw the light and it illuminated us. But the prism at its core was Waylon. Pure and honest – Waylon.

In retrospect, that moment on our friend’s back patio was a fairly perfect analogy for Waylon’s career, and a pretty good example of why I loved him my entire life. My parents’ generation were fans of the pop-country that Nashville had been peddling for well over a decade. A&M – Waylon’s first label upon arriving in Nashville – had even tried (unsuccessfully) to market him as a folk/pop singer. My parents had seen John Denver in concert at the same time Nashville was embracing him and Olivia Newton-John as a country-music savior. While many people remember Charlie Rich setting fire to the envelope that announced John Denver as 1975’s CMA Entertainer of the Year, few remember that the Male Vocalist of the Year award had already gone to Waylon Jennings. That night on a St. Louis back patio, the battle for Nashville’s soul was being played out. I don’t know what side anyone else at the party took, but I knew whose side I was on. I spent the next 24 years watching Waylon continue to chase his musical passions and seek the path that felt most appropriate for himself – record labels and audiences be damned.

I’d read about Waylon’s youngest son Shooter in Waylon’s autobiography and had seen his name credited on Waylon’s 1996 Right For The Time album. But when his first album came out, I approached it cautiously. Being the child of a legend is an insane hurdle to clear, and being born into the diminished perspective of a parent’s elevated status makes following in their footsteps seem foolish, at best. Had Pete Rose, Jr. been born to an insurance salesman and a homemaker, his baseball career would have seemed impressive. John Carter Cash is a good songwriter and performer, but his performing career suffered because while he may have outshined many of his peers, he paled in comparison to his parents. From the first notes of the Put the “O” Back in Country album, it was clear that Shooter Jennings was the real deal. Yes, he sounded an awful lot like his daddy, and yes the music had similar roots in his father. But this wasn’t like when a teenage Hank Williams, Jr. dressed in suits like his father’s and sang his father’s songs. Shooter wasn’t just impersonating his father; he had learned the same influences as his father and was beginning to explore them on his own. I was hooked immediately.

Standing in the backstage area with Shooter Jennings, I was struck by how I was seeing the next generation of Jennings perform, and I thought about fractal geometry. Fractal geometry is a subset of chaos theory, and it says that some systems – particularly chaotic systems – that appear random and haphazard are actually composed of a single geometric pattern, which is just repeated over and over and over in decreasing magnifications. Fractal geometry appears in nature: river bends, the ebb and flow of ocean tides, lightning strikes, the branching of trees. A hurricane may appear chaotic and random, but they often follow a surprising geometric rigor – the destruction they leave in their wake is a fractal dimension. It was an obvious and easy comparison. Waylon was the tree, but branches continued to spout off from him – Shooter, Struggle, Whey Jennings – and despite the difference in their styles, they were all just the next incarnation of Waylon.

I have no idea if Shooter’s live performance is designed to echo his career progression and his artistic development, but it did. The set opened with the rockin’ Southern country that he learned from his father: “Hard Lesson To Learn”, “Gone To Carolina”, “Some Rowdy Women”. These songs are Shooter’s birthright, and he owns the style the way royalty owns the crown. It’s a process most people have to dive to the bottom of a bottle to find, and Shooter makes it sound like he’s been singing these songs from birth.

And so the set continues. The crowd gets rowdier and sings along with a rowdy gusto, holding their beers aloft. Women dance and fight for Shooter’s attention. Throughout the early songs, Shooter and the band pepper some of the songs with extended riffs which Shooter directs with a headbanging motion straight out of a Metalllica show. The thing about these extended riffs is that they are just that – extended riffs. Not solos. Not improvisation. The striking part is the repetition of them. It’s not a showcase for musicianship, it’s trancelike. Shooter and the band play the same riffs over and over, and in the moments when the songs finish and the notes die away in the echoing loam of the room, the band members have clearly fallen into the trance of the music. They are leaning back, faces to the sky, mouths agape with sweaty hair falling across their faces.

But those moments were the exception, not the rule. For the most part, the set was rowdy and boozy and fun and the crowd was excited and in synch. About 15 songs in, the band played “4th of July” and the new “White Trash Song”, and whipped the audience into a frenzy. As 200 people sing along to “So I drink me a whole lot of liquor / And I drink me a whole lot of booze / I’m a midnight country-rambler / And I ain’t got nothing to lose!” it’s impossible to deny how much control Shooter can wield. Everyone may have entered the Southgate Revival House as fans of rowdy redneck rebellion, but the celebration at that point borders on transformative. This is ritual – imagery and repetition designed to help us achieve a state outside of ourselves. And as soon as Shooter achieves redneck nirvana… he plays Nirvana.

Literally. Nirvana.

Few Nirvana songs are as depressing and lonely as “Something In The Way”, and yet somehow, Shooter and his band manage to make it even gloomier. Using the same soundscape methods used in the Black Ribbons album, Shooter and the band start playing “Something In The Way” in all its isolated misery. Shooter alternates between playing a droop-tuned electric guitar and adding feedback sounds from the two keyboards in front of him. This isn’t the distortion and feedback of the Nevermind album. Shooter holds the chorus for long periods, showcasing the repetition he’s alluded to all night. And he’s adding feedback and echo and sustain from the keyboards. Nirvana’s grunge feedback seems almost peaceful, compared to what Shooter is bringing. His hands furiously twist the knobs on the keyboard, and he seems to be searching for the right keys as his fingers flutter up and down the keys. Note peek and out of the soundscape. It’s melodic, sure, but also aggressive and more than a little intimidating. If Nirvana’s version was Cobain under a bridge choosing isolation from society, Shooter’s version was the isolation of a madman. Cobain had turned away from a society that shunned him. Shooter’s version is the madman you shield your children’s eyes from. Engaging with society was never in the cards; he was simply too different. The “something in the way” in this version is the existence Shooter chose for himself.

Not surprisingly, when the song ended, more than half of the audience had left. The redneck party crowd had no idea what to make of the abrupt shift, and headed home. Those of us who stayed for the final five songs, though, were treated to more soundscape. More repetition. More ritual. And like the hurricane that was Waylon Jennings’s career, we were left with the fractal dimension that is Shooter Jennings’s career. And like the hurricane that is Shooter Jennings’s career, we were treated to broad fractal dimensions of musical vision and influence that were iconoclastic and powerful.

When physicist Richard Taylor analyzed the fractal dimensions of Jackson Pollock’s paintings, he realized the Pollock’s “drip” technique followed a very specific pattern. Mathematicians can quantify fractal dimensions on a scale between 0 and 3 – the less chaotic the fractal, the lower the number. When mathematicians compare works of art against their fractal calculations, they find that we find art with lower fractal dimensions more aesthetically pleasing. Art which mirrors the rolling of the tides is the most aesthetically pleasing. Early Pollock paintings had gentle, pleasing fractal dimensions around 1.4, similar to that of a long coastline. Pollock’s final paintings, however, were his highest fractal ratings. Taylor assumed that Pollock was trying to test the limits of people’s capacity for what they could find aesthetically pleasing. That’s a brave decision.

When one looks at a Thomas Kincaid or a Katy Perry, we see artists whose entire purpose is to isolate the artistic elements which appeal to the broadest audience and ensure they fill their work those elements. Pollock, on the other hand, looked to push to the outer limits of beauty. And that’s no way to win a massive audience. Similarly, Shooter was literally chasing the audience out of the hall with his sounds. In the second-to-last song of the night, Shooter sang “It was so beautiful / It was so peaceful / All the destruction.” from “All Of This Could Have Been Yours”. No truer words were spoken that night. Shooter Jennings asked the audience to see just how much they were willing to go to the edge, artistically. If you needed the musical equivalent of the long coastline, Shooter could provide it. But as the night progressed, he asked us to push closer and closer to the edge with him. It’s similar to asking people to find the beauty in a thick copse of trees or a jagged mountainside. The beauty is there; you just have to work a little harder to see it. You may need to trust your guide a little more than normal.

When the show ended, I was heading down a set of stairs as an exhausted-looking Shooter was heading up. All I could think to say as we crossed paths was “Thanks for that ending, man.”

A father comes to Nashville in ’62 and finds the direction of the place at odds with what he wants to do. And he continues to follow his instinct.

A son returns to Nashville in 2004 and finds the direction of the place at odds with what he wants to do. And he continues to follow his instinct.

A father loves music and brings in as much influence as he can handle, and despite the breadth of his knowledge and influence, even his ardent fans see him through one specific lens.

A son loves music and brings in as much influence as he can handle, and despite the breadth of his knowledge and influence, even his ardent fans walk out of a show when he changes direction.

A father doesn’t give a fuck, anyway, and walks his path.

A son doesn’t give a fuck, anyway, and walks his path.

Shooter Jennings, you beautiful fractal motherfucker. Keep pushing, son.

I was there, I remember it well. There were alot of nights on my Dad's back patio…great work here…Thanks for sharing.