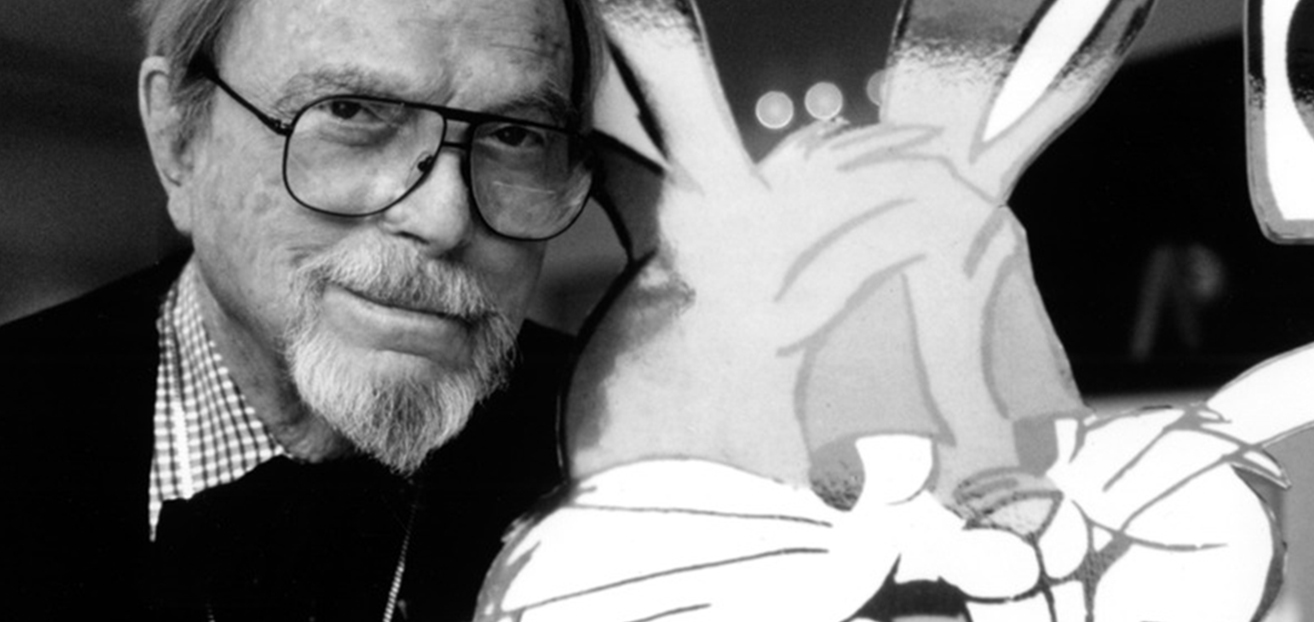

CHUCK JONES: September 21, 1912 – February 22, 2002

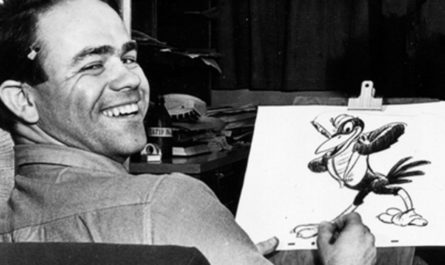

I think every parent attempts to introduce their children to the things they loved as a child, with the hope that their children would have a similar positive reaction. It also seems to me that these introductions fall flat about 80% of the time. I got lucky with Sesame Street and certain Jim Henson shows. I missed with The Doors and Willie Nelson and The Dukes of Hazzard. But I remember the excitement I felt when Chuck Jones cartoons became available on iTunes years ago, and I was able to purchase Duck Amuck for my iPod. I had hoped my kids would love it as much as I did, and as luck would have it, they did. They would regularly watch it while we were driving somewhere, laughing at all the same gags people had laughed at for 55 years.

It’s nearly impossible to pinpoint what is the best aspect of Chuck Jones’ work. Writers and comedians will point to his gags and his impeccable comic timing. Animators point to Jones’s ability to make limited animation so stylized that it became its own genre. Artists point to Jones’s impeccable layouts and masterful use of color and design to create mood. And fans of cartons just love that Jones’ cartoons are uproariously funny. When Chuck Jones was named a director at Warner Brothers in 1937, he had already worked with many of the greatest animation directors of all time: Ub Iwerks, Tex Avery, Frank Tashlin, Friz Freleng, Bob McKimson, and Bob Clampett. His time at both Iwerks Productions and Warner Brothers had taught him the fundamentals, and he literally had a pick of many of the greatest cartoon stylists to emulate. But Jones didn’t emulate any of them. He didn’t even appear to pick and choose elements into a pastiche of styles. At 25, Jones jumped onto the scene as a director with his own unique, very identifiable cartoon style. That’s an amazing fact, given that Jones learned animation under the tutelage of these masters, and the work of an animation director is so influential, one could easily assume his work would have to show some direct influences.

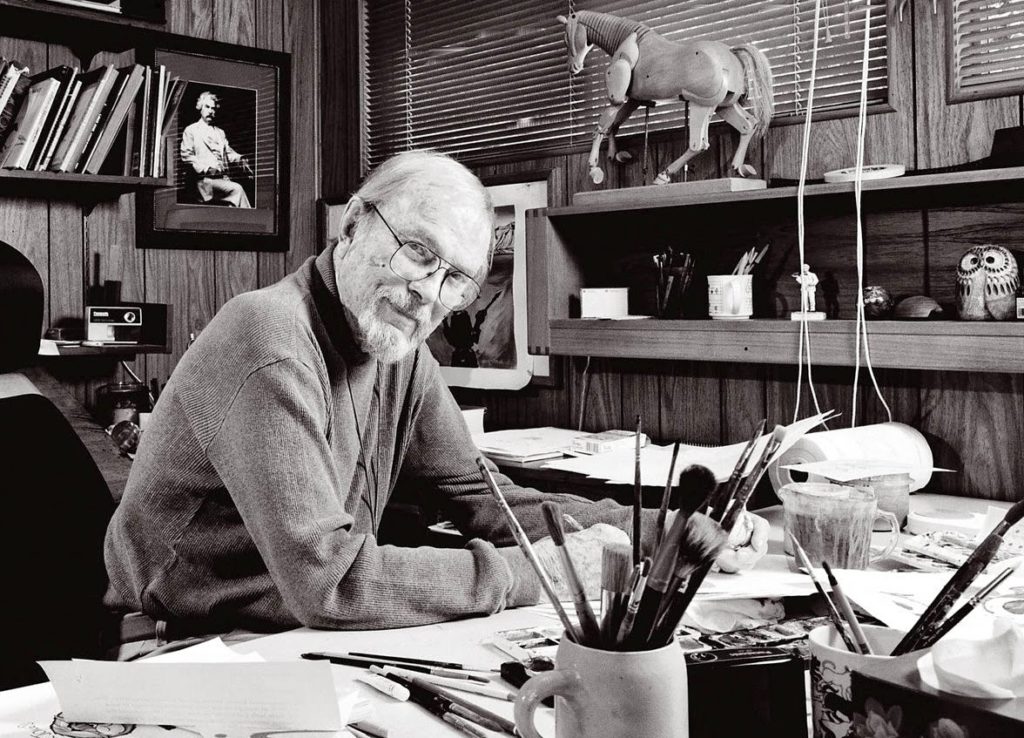

The work of an animation director is not as simple as directing a live-action film. Animation directors supervise the writing of the script. They time out all the gags, in both the audio tracks and the animation. The draw every key pose (called “extremes”) for the entire cartoon, so animators can then draw all of the interstitial drawings (called “in-betweens”). Animation directors’ visions are so complete that you can give two directors the same script with the same gags and the same audio tracks, and you will end up with two very different cartoons. But in order to accomplish this, both directors have to have faith in their own creative visions. Some artists take decades to find that faith. Chuck ones had it at 25, and it was a lesson he had learned even earlier, when he was an art student at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles. Jones had been such a strong student in high school that he had grown bored and his grades began to slip. Worried that Chuck would derail his education due to boredom, his father arranged to have Chuck graduate high school at 15 and enroll in art school. Chuck’s classmates were mostly in their 20s. Many had already completed undergraduate degrees, or had worked professionally as artists. Jones was intimidated and afraid, and he felt he could never measure up to his classmates. One evening, he described his feelings of inferiority to his uncle by saying, “You can’t turn a pig into a racehorse!” to which his uncle replied, “No, but you can make a really fast pig.”

That was the turning point for Chuck Jones. There was freedom in knowing that artists don’t create competitively. Art is not a horse race; it’s an attempt by every participant to go as far and as fast as they can, regardless of the pace of anyone else. There was no need to worry about the talent or skill of anyone else. There was no need to feel inferior or superior. There was no need to follow someone, or to go in a contrary direct in because someone had already gone where you want to go. For Chuck Jones, art was about the freedom to express himself, completely separate from the influences and limitations and guideposts of the masters who came before him. Because if the best art is entirely personal, the best art has to lose that sense of comparison. It has to lose the self-judgment that comes from comparing our art to the art of others. Had Chuck Jones spent a career trying to out-do Tex Avery or Friz Freleng, we never would have seen a Chuck Jones cartoon. Instead, we’d have seen a poor reflection of Avery or Freleng’s work. Chuck Jones refused to compare himself with the geniuses he learned from, and the resulting gift to us was truly original animation that remains hilarious and brilliant a half-century after it first appeared.