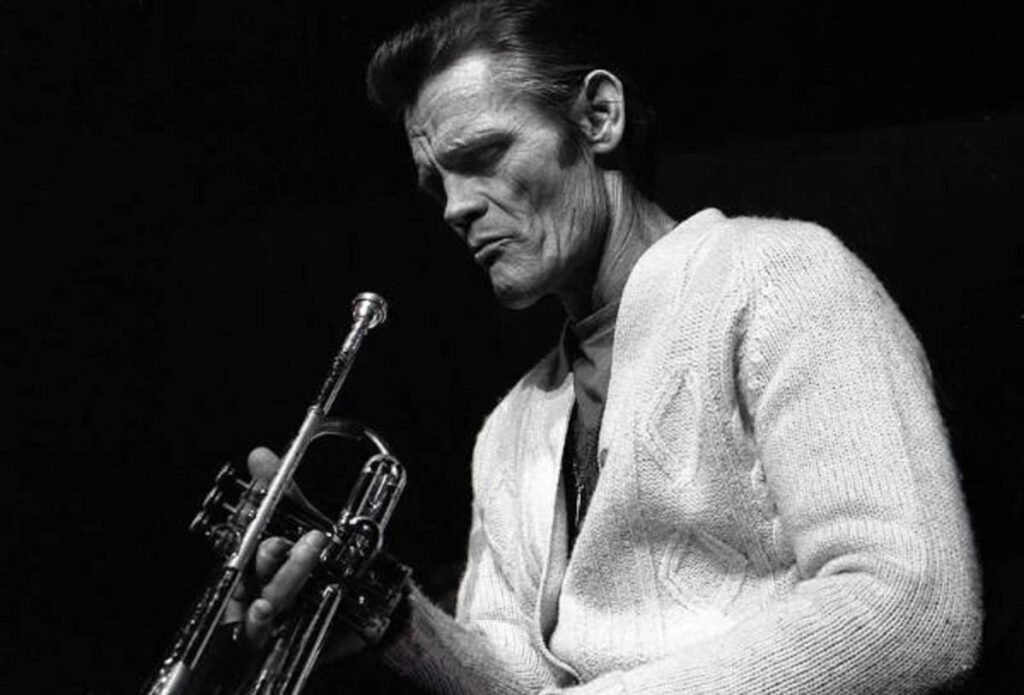

CHET BAKER: December 23, 1929 – May 13, 1988

My wife is a talented musician. If you were to ask her, she will tell you that she works hard at being a musician, but she will downplay her abilities. On the other hand, she regularly gets frustrated with me because I rarely pick up any of the instruments I’ve tried to learn over the years, preferring instead to sing, which is something I never trained for or practice or even have to think about. It’s as natural for me as speaking. The level of commitment irritates my wife. She’s a passion-follower; when she feels something strongly, she throws herself headlong into it and works tirelessly at mastering it. I’m on the other end of the spectrum. I try something, and if I’m not naturally gifted, I never try it again. And if I am naturally gifted, I may try it for awhile, but if it is more effort than fun, I tend to stop trying. To her, this is an outrageous and immature position. But things that come easy to people aren’t necessarily the gifts that they would be to dedicated souls like my wife’s. Sometimes, they can be a curse.

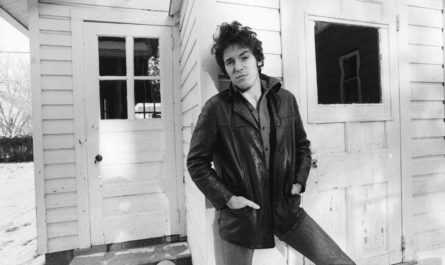

I was a few weeks from graduating high school when I heard the news of Chet Baker’s death. As an obsessive Sinatra fan, I knew Baker’s name but very little about him. The news focused on the grisly details of his death: dead on the street, heroin in his hotel room, his long exile from America, his decades-long drug addiction. The news segment never played a note of his music. But they showed a picture of him in the last years of his life, his face craggy and strung out. Then they showed one of the early William Claxton photographs of Chet, looking like the male model who gets hired for the cologne ad because of his striking resemblance to James Dean. I soon went to the library and checked out “My Funny Valentine” and one of his later live albums.

The thing about Chet Baker was that he made it look so effortless. When I first played “My Funny Valentine”, I assumed he was a vocalist. The news talked about him as a legendary jazz trumpeter, but maybe I had misunderstood. Clearly, this guy was no Sinatra, but he wasn’t trying to be either. His vocal stylings were more like Louis Armstrong than Sinatra. Baker’s voice was serene and breathy, and while he may not have been as beholden to the rhythm and timing of the song as Sinatra, their approaches differed. Sinatra was like an alien had been dropped on earth with a completely different understanding of tempo and rhythm than mortal humans. Baker played with the measures of the song the way a musician plays with them. He calmly bent the rules enough to make you notice the beauty of his voice and his phrasing, and then somehow got back in with the song at just the right time. His vocal phrasings were masterful and intentional. So I was shocked to find out that Chet Baker wasn’t a singer, but a trumpet player who also could sing.

Chet Baker was another one for whom things just came easily. This is not to say he didn’t work hard, but his talent is so natural and so ingrained, he seemed to spend much of his career going against the grain. Baker’s horn always seems to be standing in contrast to the song. Unlike other players who play slightly above the song to showcase their talent, Baker’s horn runs on a totally different track. Baker would take songs with basic diatonic structures like “Zing! Went The Strings Of My Heart” and blow fast, inprovised meoldies over them. On uptempo numbers like “My Little Suede Shoes”, Baker is keeping pace with the song, but sounds as laid back and relaxed as he could play. It’s a marvel he’s always keeping up.

I won’t say that Baker’s massive drug problem was the result of his natural talent. After all, reports of the New York jazz scene in thr 1950s describe heroin taking out musicians like ducks in a shooting gallery. One by one they fell, at a seemingly unstoppable pace. But many eventually escaped the grip of that addiction. Baker, who had much going for him than most, did not. His later albums were recorded after Baker lost his teeth after a beating he took in a drug deal gone bad. He had the teeth replaced with dentures, and then learned an entirely new embouchre and got himself back to playing. Plenty of trumpet players can’t survive the slightest change to their mouth. A lost tooth is the same as a massive rotator cuff tear for a baseball pitcher. It’s not an easy setback to clear. Baker was able to do it on heroin.

Natural talent may not have been Baker’s curse, but he certainly never gained the sense to protect and defend his talent the way Miles Davis and John Coltrane eventually did. Baker could play gigs so powerful they would master the sound engineer’s recordings, and then go sleep in the back of a car on the Amsterdam streets. His actions were not the actions of somebody who had struggled so much they refused to let anything take their efforts from them. For Baker, it seemed more effortless. Like a gift he had been born with, and one he truly seemed to enjoy and appreciate, but never with the fierce protection that comes from having crafted something from bloody and overworked hands. And so what appears to be a blithe trashing of the gift may be something different. It may just be that Baker was appreciative, but never felt a sense of stewardship for his gift. It’s an easy trap to fall into when something comes easily to you.

And so when Baker died on the Amsterdam streets – some reports say it was an accident, others say a suicide – it’s easy to look at a career where he forsaked his gifts. But he carried those gifts to the bitter end. Or perhaps they carried him. When things come easily, it becomes impossible to tell.