HOMESTAR RUNNER: Launched January 1, 2000

My children are at the age where they ask theoretical questions to initiate conversations about values and desires. A common one is “If you won the lottery today, what would you do with the money?” My answer is always the same, and it always surprises me a little. “I would make cartoons.” Not sure what it would look like, exactly. Not sure if I would make them on my own, or start a company, or whatever. I just know that I love animation (particularly cartoons). I love the humor, I love the silly voices, I love the absurd magic of the physicality of cartoon characters. And the idea of creating those kinds of worlds has appealed to me since I was a very young child. In my life, I’ve been lucky enough to be able to animate things for eLearning lessons I’ve created, and I’ve done some character designs. I’ve had ideas for cartoons for years, but like so many dreams, I went through my twenties with a much longer “Cons” list than “Pros” list for making cartoons. And the “Cons” list was rational. Cartoons were distributed by studios. Drawn in Korea. Written in Hollywood. Of the thousands of cartoons pitched per year, fewer than a dozen were ever made. I hadn’t attended art school, or learned animation. Vocal studios were expensive. The idea of making a cartoon from Chicago was seemingly impossible.

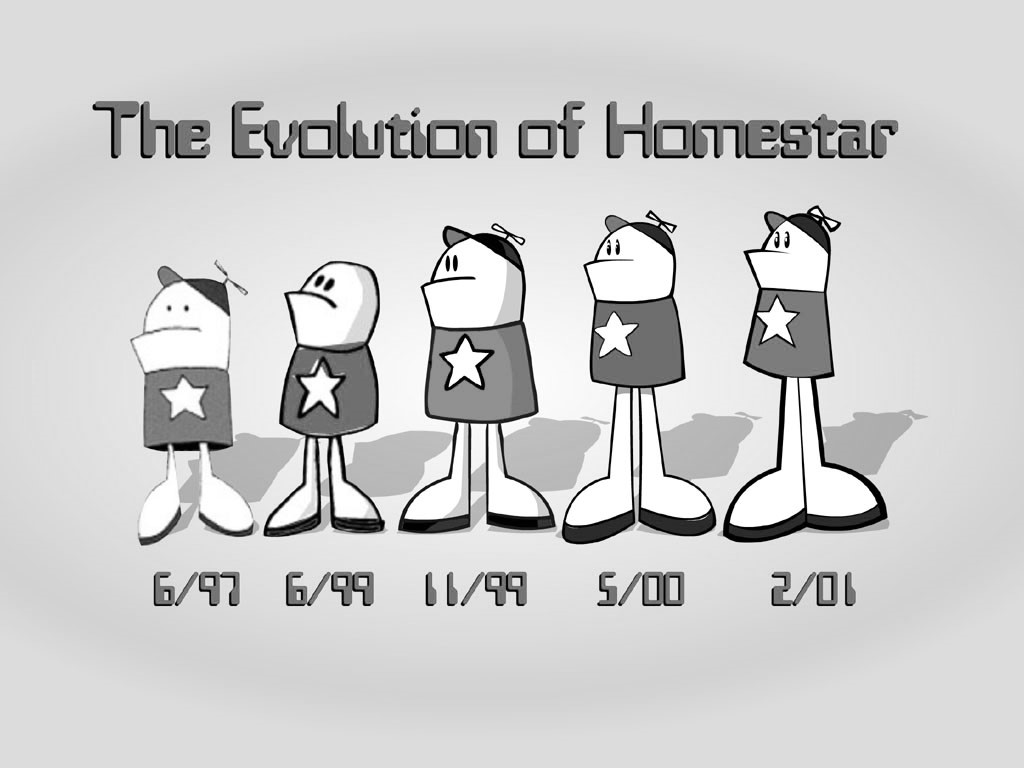

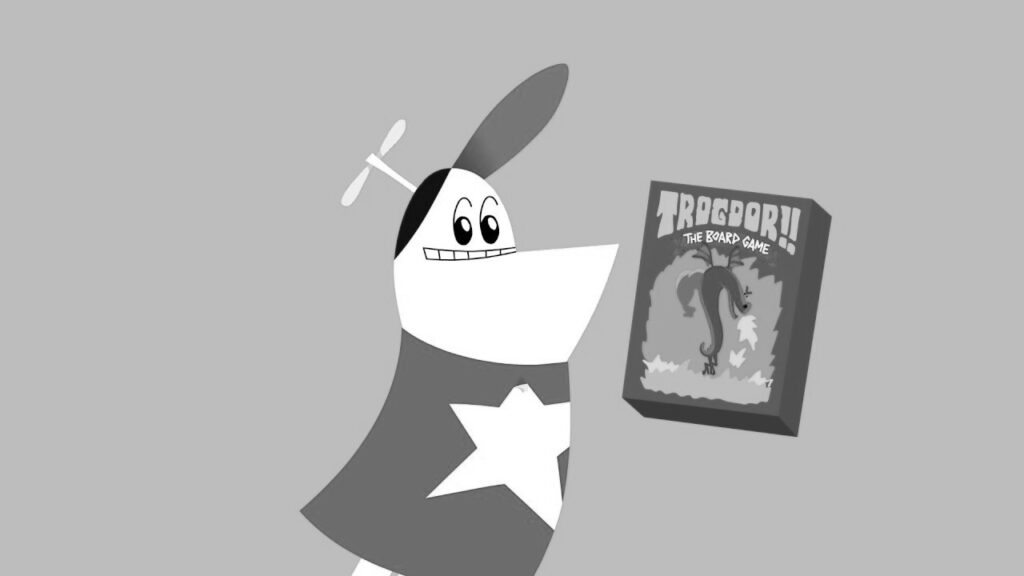

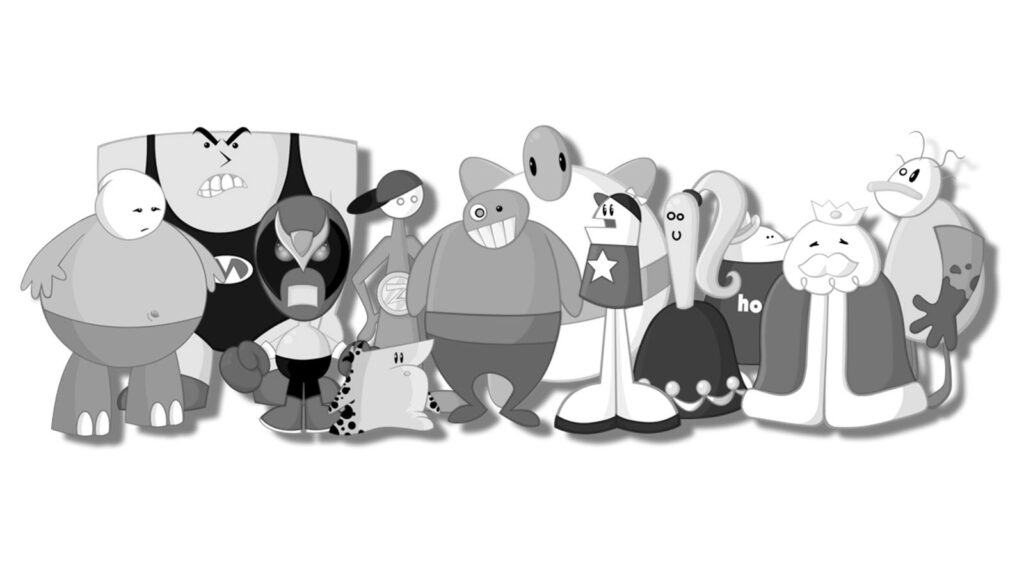

In 2000, however, two brothers from Atlanta changed that paradigm completely. Using a modified version of Macromedia’s Flash, they took a character from a joke children’s book they had written a few years before and created a cartoon. Then they posted it on a website, and the world of Homestar Runner was created. Unlike so many other early Web properties, Homestar Runner remained a success for years. Throughout its ten-year run, the characters evolved in both style and content. The focus of the cartoons changed as characters became more popular (notably, the cartoon’s antagonist, Strong Bad). Designs became cleaner and – despite the severely limited animation – the humor remained both funny and acceptable for all audiences. Even though the universe of Homestar Runner was fully-formed when it first appeared, the Chapman brothers used the next ten years to fine-tune it and constantly give it both depth and absurdity. Eventually, even throwaway gags began to take on a life of their own, and in one case (Teen Girl Squad) received its own series.

When the Chapman brothers stopped making Homestar Runner cartoons in 2010, they’d spent a decade creating a world that supported itself in merchandising revenue; the brothers refused to accept advertising dollars. Occasional video work for popular alternative groups like They Might Be Giants and Of Montreal led to indie credibility and writing offers for creative shows like Gravity Falls and Aquabats. There was no grand goodbye (not uncommon for Web properties), but just a slow fade into history. Their website and its store remains open, but almost no new content has been added in four years. What the Chapman brothers created was a legacy that democratized cartoons (and set a tone for most creative arts). 1999 was the time when home internet download speeds began to pick up. It was a time when Macromedia found a way to create vector-based animation with file sizes that were not enormous. It was a time when people began to own their own domains and create their own websites. And when that moment of convergence arrived, the Chapman brothers were ready to accept the challenge. Leaving talent aside, they forever changed the model that had kept people like me from making the leap into creativity.

In almost an instant, the hurdles that kept creative people from creating were made non-existent. No longer could a talented musician living in the middle of nowhere be relegated to obscurity because she didn’t live in New York, Nashville, or L.A. No longer could a talented writer claim “lack of access” to literary agents and (subsequently) an audience. In the ten years since, audiences have become even more available. Blogs, YouTube, Facebook, Vine, even Twitter have created audiences for talented people regardless of their age or location. What the Chapman brothers showed us (years before YouTube would make it ridiculously easy) was that we had no excuses for not creating. That our excuses were now entirely self-imposed. Because art could be created and shared with the entire Web inexpensively. The only components not guaranteed were talent and motivation. As it turns out, those hurdles are more pronounced for some of us than we could ever imagine.

When my kids and I dream of unimaginable wealth and what we’d do if we had it, I always say “I’d make cartoons.” Fortunately for me, they’re not yet at the age where they think to ask, “Why not just make cartoons now, dad?” It’s a logical and fair question, and I dread the day they ask it. In truth, Lotto-sized wealth makes the dream possible because there is no failure or downside. There is no chance of me screwing up, or worse yet, finding out that – despite how much I love and know about cartoons – I may not have any talent in that arena. Any indication of that reality could be mitigated with the hire of a more talented artist or writer. Even if you’re just the guy signing the paychecks, you’re still a part of the “cartoon making” process. But the Chapman brothers never afforded themselves that luxury. They simply started making absurd cartoons about a ridiculous universe. And they kept at it – day after day, month after month, year after year. I don’t know if the Chapman brothers are shy or if the nature of the press just never covered them extensively, so I have no idea what their motivations were, or if they ever had moments of doubt or fear. What I do know is they faced the most primal fear of creative types: the fear that the thing we love is also something we can’t create. And in the face of that, they took the most vital step you can take when the excuses of money and opportunity are lifted. They simply created something. Then they shared it. Perhaps they were frightened and unsure of their abilities the entire time. Perhaps that’s what keeps most of us from creating when everything in our life allows us the freedom to create. But the critical process remains the same.

Ignore the fear. Then take the first step. And then just keep stepping.