THE LEGEND OF “STAGGER LEE”: Occurred December 27, 1895

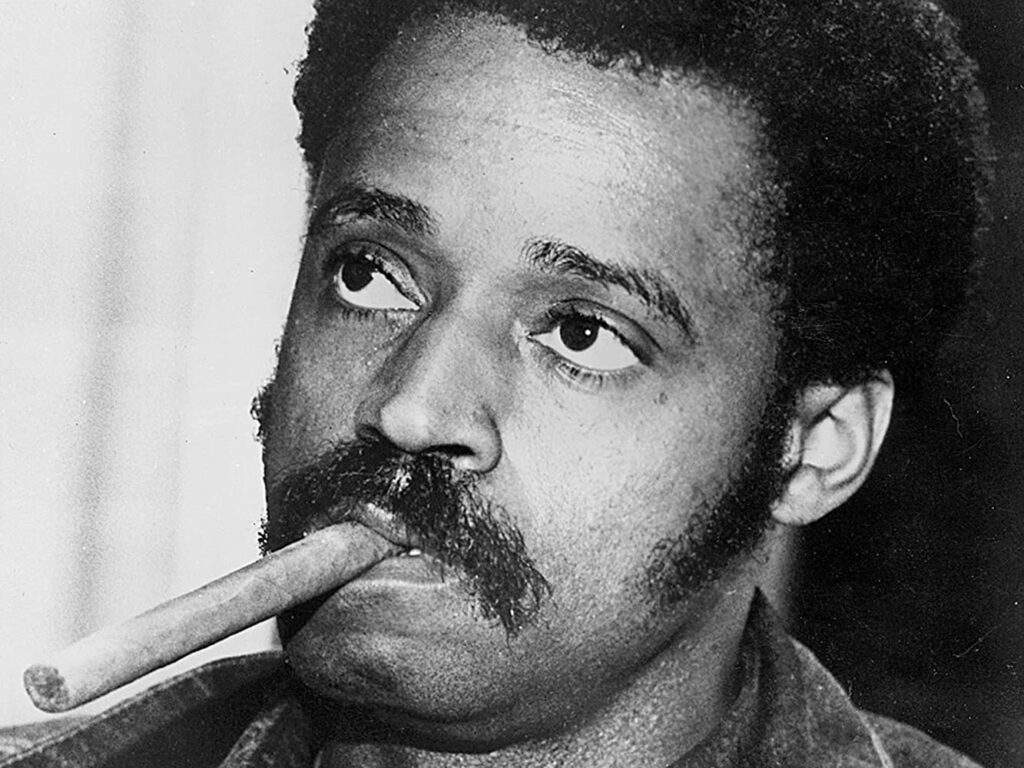

In the early part of the last decade, a close friend of mine had asked me to give a lecture to his Introduction to Film class at Ohio State about blaxploitation films. I had him show the class Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song in the previous class session, and we could discuss it during my lecture. When I showed up for the lecture, he admitted that the all-white class had staged a mutiny and forced him to shut the film off after about 45 minutes, and then walked out. It was shocking to me. They were more shocked to learn the story of Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song, and how it made millions of dollars playing to primarily black audiences in major cities, including a years-long run in Oakland where it was required viewing for Bay Area Black Panthers. More specifically, they couldn’t understand how I refused to classify Sweetback as “blaxploitation”, or even “exploitation”. The thing that they didn’t understand was the power of normative behavior. White college kids in the Midwest have spent their lives seeing images that are familiar and comfortable. The TV shows they watch, the movies they see all are filled with white people doing things they understand. Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song was filled with images they’d never seen, and it seemed ridiculous and cartoonish. To others, though, it was just the story they were waiting for.

On December 27, 1895 in a bar in the “colored” section of St. Louis, two levee hands – William Lyons and “Stag” Lee Sheldon – got into a political argument in Curtis’ Saloon. Emotions boiled over and Lyons snatched Sheldon’s brand-new white Stetson hat from Sheldon’s head. According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Sheldon drew his revolver, shot Lyons in the stomach, and then walked over to the man as he lay bleeding out, snatched his hat from Lyons’ hand, put it back on his head and calmly walked away. The tale would quickly become legend, and “Stag” Lee’s name would quickly make its way up and down the Mississippi River, changing here and there. In some re-tellings, he was “Stack” Lee, in others he was “Stag-O” Lee. In 1928, Mississippi John Hurt recorded the first song in his honor, where he sang of “Stack O’Lee”. Most commonly, he became known as “Stagger Lee” in countless versions of his tale. And in each version, Stagger Lee was the ultimate badman. In most versions, not only does Stagger Lee shoot Billy, but he isn’t even pursued by the law because the law is terrified of him. When Lloyd Price left that particular part of the story off his 1953 version of the song, it became a huge hit, and while on the surface his version appeared to simply be a song of violence, Price also included numerous references to The Battle of Jericho (“leaves came tumbling down”/”walls came tumbling down”, horn blasts to precipitate massive chaos) which was a favorite topic of Mahalia Jackson songs, as The Battle of Jericho was often used in spirituals as an allegory for abolition. Regardless of what version of the Stagger Lee story you hear, they all point to the same thing – a tale of an African-American who finally grew tired of having a foot in his ass, and did something about it.

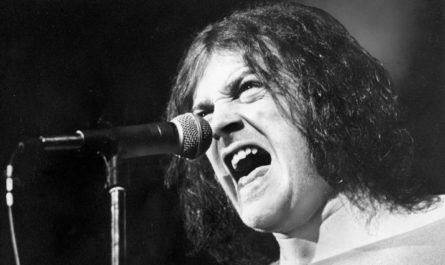

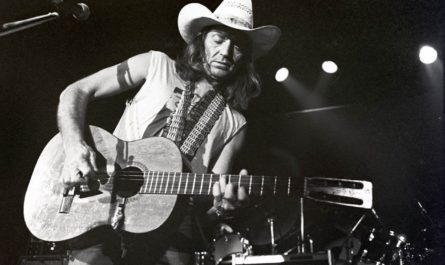

James Baldwin once said that music was the only way African-Americans have been able to tell their story, because “a protective sentimentality limits [America’s] understanding of it”. Consider the text of Lloyd Price’s version. In his version, Staggger Lee and Billy are gambling. Billy wins Stagger Lee’s hat and then tries to cheat him out of more money. Stagger pulls his gun and Billy pleads for his life. He tells of a sickly wife, and three kids who will surely be orphans if Stagger Lee shoots. Stagger, in return, shoots him clean through the abdomen. This is not a story of “right versus wrong”; Price’s chorus is the raucous “Go Stagger Lee! Go Stagger Lee!”. This is a tale of a reckoning, and yet it rose in the charts during the heyday of Jim Crow, precisely because a protective sentimentality never forced anyone to address the idea that deep in the heart of an entire race of people was a murderous dream of a vengeance so brutal, nobody would ever dare stop it. Consider, too, the white-people version of “Stagger Lee”: Jim Croce’s “Bad Bad Leroy Brown”. Croce’s set-up is similar, but in his version, “the baddest man in the whole damn town” gets sliced up by a jealous husband in the only conflict in the entire song.

Therein lies the difference in the audiences for these songs. To a privileged audience, the brutality and violence of a badman will always be punished, eventually. Leroy Brown may be the baddest man in town, but his sins will not be overlooked. But underprivileged audiences rarely hear their own stories told, and so when they do, they want to hear the story of the man who stood for himself without fear of – or actual – reprisal. The irony of this entire argument is that I have no actual visceral connection to Stagger Lee; my understanding is purely historical and sympathetic. But I do have a visceral understanding of the need to see the stories that reflect your beliefs, and the stories that allow you to tell the world who you are – as opposed to the “you” they have defined. And sometimes that story takes on an ugly (but necessary) form. On a late December night, just a few decades after the Civil War, a young man and a new hat created a story that still resonates today. Simply because so few people have the latitude to demand even a moment of life on their own terms the way “Stag” Lee Reynolds did in Curtis’ Bar. That we don’t recognize the power in those moments doesn’t make them not real, or unworthy of our time. Turning off the movie when the narrative is foreign to us is not just denying the work outside of our personal narrative, it’s denying the people to whom that narrative speaks. I have to wonder if the tales of standing up to oppression wouldn’t be less murderous and terminal if they were just heard more. If the very idea of a minority demanding to live a life without insult or oppression – even if only for a brief moment – weren’t so rare that it could only happen by the hero shooting his way out. Because boiled down to its essential nature, the demand for equal rights and equal protections will lead to a world where every group’s narrative is not only seen and heard, but accepted as “typical”. True equality is when I notice my neighbor’s race or sexual orientation with the same lack of judgment with which I notice the color of their house.

Because we can’t expect anyone to accept the morality tales of Bad, Bad Leroy Brown until the taking of Stagger Lee’s hat no longer has meaning.