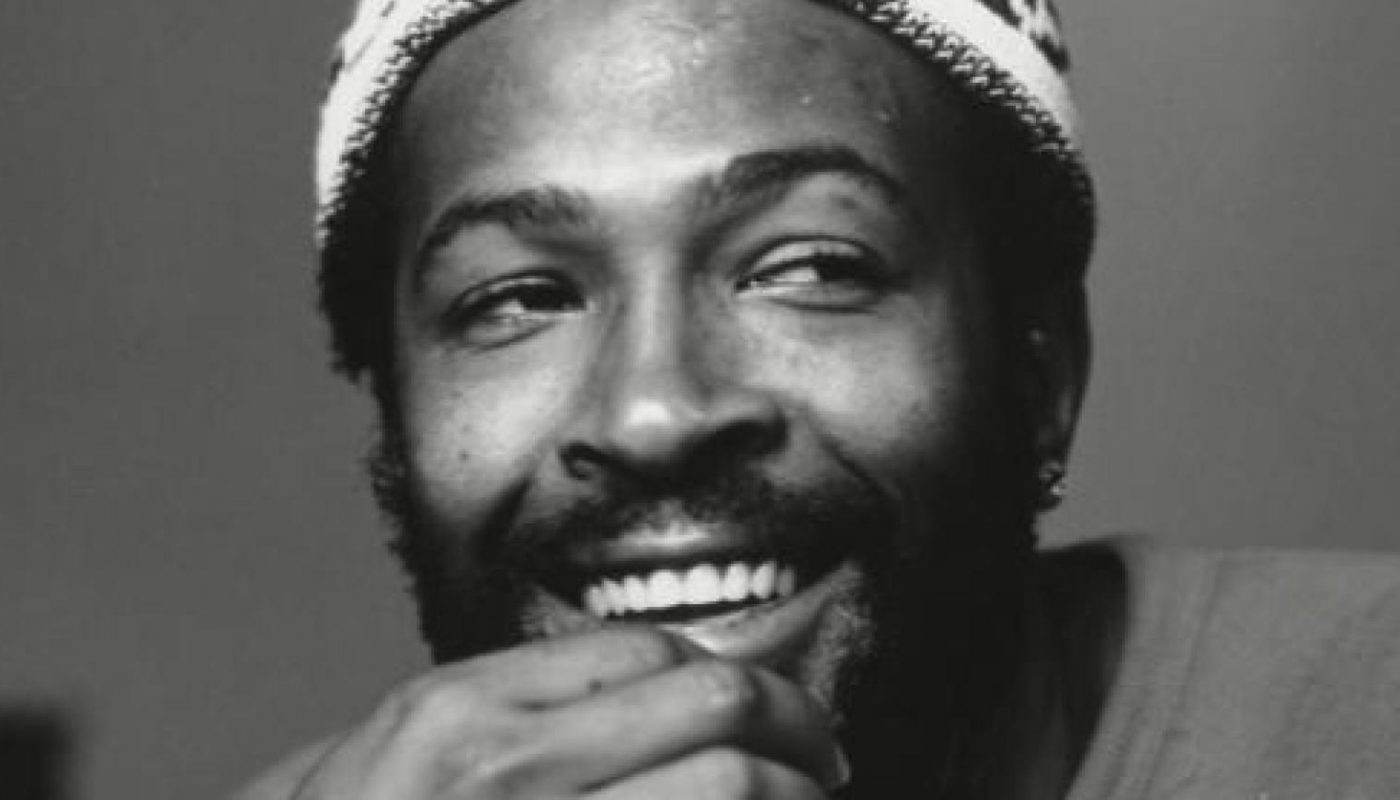

MARVIN GAYE: April 2, 1939 – April 1, 1984

When I try to describe the way I sing, I tend to refer to the singers I emulate. I deprecatingly say that my voice sounds like a weaker, less soulful version of Joe Cocker or Otis Redding. Interestingly, one of the comments I regularly hear is that I sing “like a black guy”. It’s a roundabout way to call me a soul singer, which has always been a name that we don’t easily assign to white males – particularly white males raised in privileged surroundings. We regularly diminish or qualify that designation, often calling it “blue-eyed soul”. Even I am uncomfortable calling myself a soul singer, because my earliest exposure to soul music was songs in which the voice and emotions of the singer resonated with me. But it was Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On that first brought me to understanding why soul music was widely-considered a black genre. In one album, Marvin Gaye – known before the album’s release for silk-smooth love songs and moody remakes of earlier Motown hits – walked America through the dramatically-shifting landscape of African-American protest. More importantly, he created an emotional portrait of the depth and breadth of a marginalized culture. What white America saw as an indistinguishable group, Marvin Gaye showed as varied and complex, reacting to different types of threats in different ways. Some argue that What’s Going On is the quintessential protest album. Others label it the quintessential soul album. Either way, when I first heard What’s Going On, I remember wondering if I could ever reach into myself and communicate that broadly, yet honestly. I remember wondering if anyone raised like I had been could. Thirty years later, I still wonder.

The timing of Gaye’s recording of the What’s Going On album came at a tumultuous time for the musician. Gaye’s singing partner Tammi Terrell had died from long and painful battle with brain cancer a year before, and Gaye had gone into a depressed seclusion. The sixties had been a decade of stops and starts and changes in direction for him, creatively. He was wrestling with drug addiction, and his brother Frankie had been drafted and sent to fight in the Vietnam War. Motown founder (and Gaye’s brother-in-law) Berry Gordy had decided to pull up roots from Detroit, noting a diminishing lack of civic pride in the city, and moved Motown Records management to Los Angeles. Gordy left his massive house, known as the Motown Mansion, to his sister and Gaye. Grief-stricken, Gaye spent the year feeling abandoned and marginalized and neglected and resentful. He traveled around the United States, witnessing a rising anti-war political tide. One protest led to an act of police brutality that stuck with Gaye, and he decided to write about it. Returning to the Hitsville, U.S.A. compound of Motown Records in Detroit in early 1970, Gaye recorded the single “What’s Going On”. It was the first time Gaye had written, arranged, performed, and produced a song, and it was a true testament to his artistic vision. Gaye had always been known for his three-octave vocal range, and how deftly his voice could change to accommodate the emotional nuances of a song. Gaye’s voice could be a growling baritone rasp, a smooth tenor, or a flighty falsetto. On “What’s Going On”, Gaye used the studio to use all three voices at all times. Sometimes in harmony, but not always. Sometimes in the same tempo, but not always. If the true merit of a soul song is the way the singer uses their voice to convey emotion, “What’s Going On” is a shotgun blast of soul. The layering of Gaye’s voices highlights that this song isn’t about Gaye, it’s about the black protest struggle. It’s about everyone in the black community (and beyond) who was struggling to understand how the world had turned so bad, so quickly. It was a masterful effort of writing, performing, and producing.

Unfortunately, Motown Records didn’t see it that way. Concerned over the backlash of releasing a political protest record (much less of a protest record that highlighted the black struggle), they refused to release the record. Gaye demanded to be released from his contract, and Motown refused. Gaye had achieved a measure of success with the political “Abraham, Martin & John” on his album the year before, and new that audiences would not flee from overt political sentiment in a song. Gaye went on strike until Motown agreed to release the single. It would take a year, but the single was released with the agreement that Gaye would record one more album with Motown, and then he would be released from his contract. In January, Motown released the single and immediately rocketed to #1 in the R&B charts. By March, Gaye was in the studio for ten days recording and producing the What’s Going On album.

What’s Going On was eye-opening for me in that Gaye used the studio to maximize his vocal presence, but the lyrics he penned truly maximized the black experience of the time. The album was a song cycle, beginning and ending on the same lines, but in between, he wandered through economic realities, the Vietnam War, drug addiction, disenfranchised children, the church, the ecology, and a final song that described the blues of the inner city ghettoes with a complexity otherwise unseen in white-owned media. Listening to the album made me realize that there was a world out there that was far beyond anything else I had experienced from Motown. It was the late 1980s, and while the Vietnam War-era society being discussed was nearly two decades in the past, the politics being discussed clearly still existed. And they were unlike anything I had ever experienced in life, but more importantly, they were unlike most of the things I had been taught. Not that I had been fed intentional lies about black society, but black cultural issues were largely ignored or marginalized. Viewing that culture through the prism of Marvin Gaye’s lyrics and vocals exposed a society broader and deeper than I had ever imagined. And while I didn’t covet the struggle, I recognized that it was this complexity and this frustration that not only made What’s Going On so deep, it was what gave the emotional gravitas I loved in Otis Redding’s love songs, or in even the brightest and poppiest of Motown hits. I had heard white Vietnam-era protest music growing up, but I instantly recognized this is far more soul-searching, and far more important. I was too young to know why or how, but it was apparent from the earliest listens that What’s Going On was ne of the most important albums of all time.

In an interview a few years ago, Daryl Hall argued against the label of “blue-eyed soul singer”. Despite the 80s pop bubble of Hall & Oates, Daryl Hall was primarily known as a soul singer, and a damned good one. By labeling his music “blue-eyed soul”, we declare that soul music by white men is an aberration that needs to be qualified. I understand his point from a logical perspective, but in all honestly, when I think of What’s Going On, I find it hard to label myself – or anyone born into privilege, including Daryl Hall – as a soul singer. Because it’s hard to accept that any amount of pain or suffering I’ve experienced is drawn from a deep enough well to earn that moniker. But unlike Daryl Hal, I don’t think “blue-eyed soul” has to be dismissive. Because if I learned one thing from What’s Going On, its that the best songs come from the very core of your soul. You pour every bit of honest emotion into them. And maybe the pains you’re sharing aren’t as bad as someone else’s. Maybe your love isn’t as strong as someone else’s. Perhaps your losses aren’t as severe, and your fears aren’t as grave. As an artist, your job is to commit t those feelings and share them as honestly as possible. “Blue-eyed soul” may just be a way of saying, “soul that comes from a more privileged space”, as opposed to “fake soul music”. Either way, Marvin Gaye set the bar for soul music with What’s Going On, and black or white, anyone who wants to follow in those footsteps must follow in a space of total emotional honesty. Because Marvin Gaye knew that the world we’re singing about deserves nothing less.