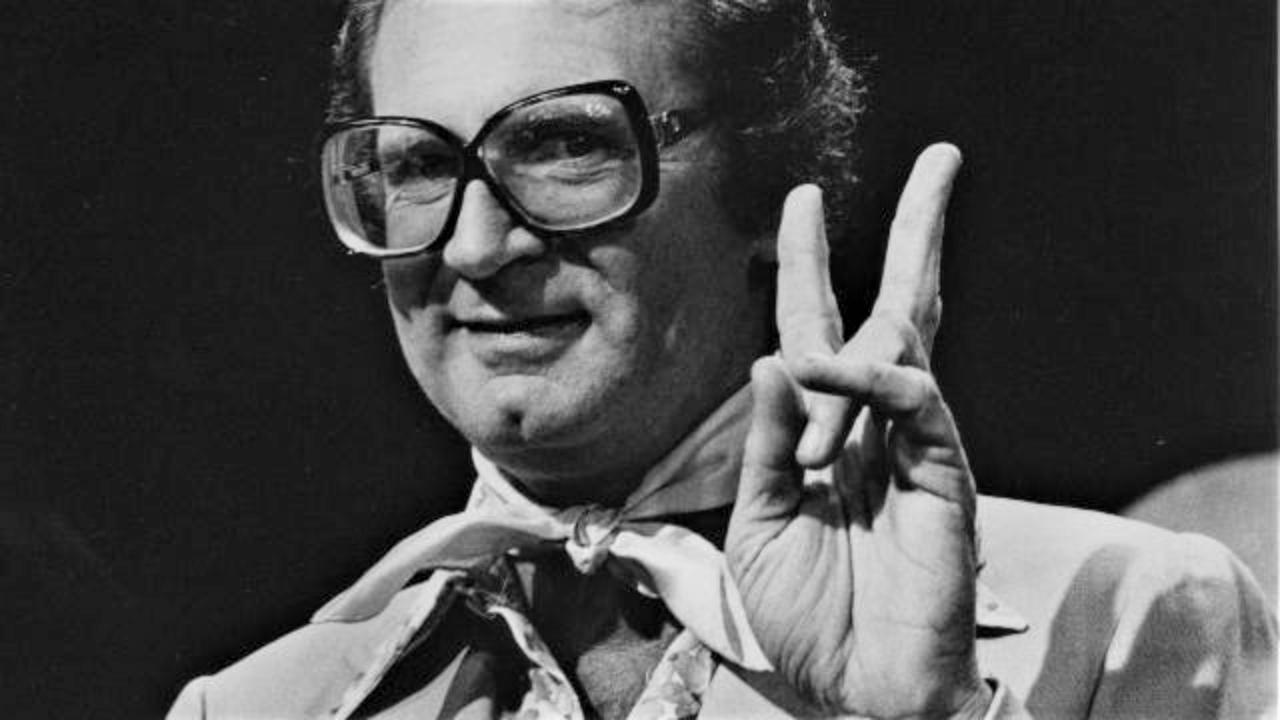

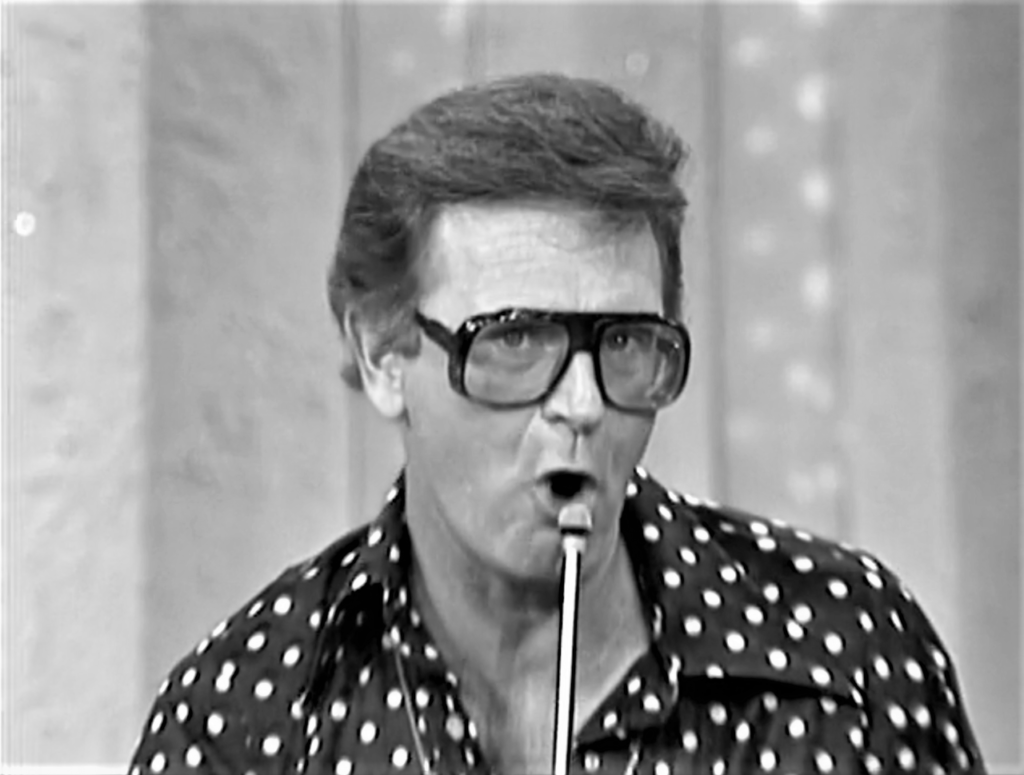

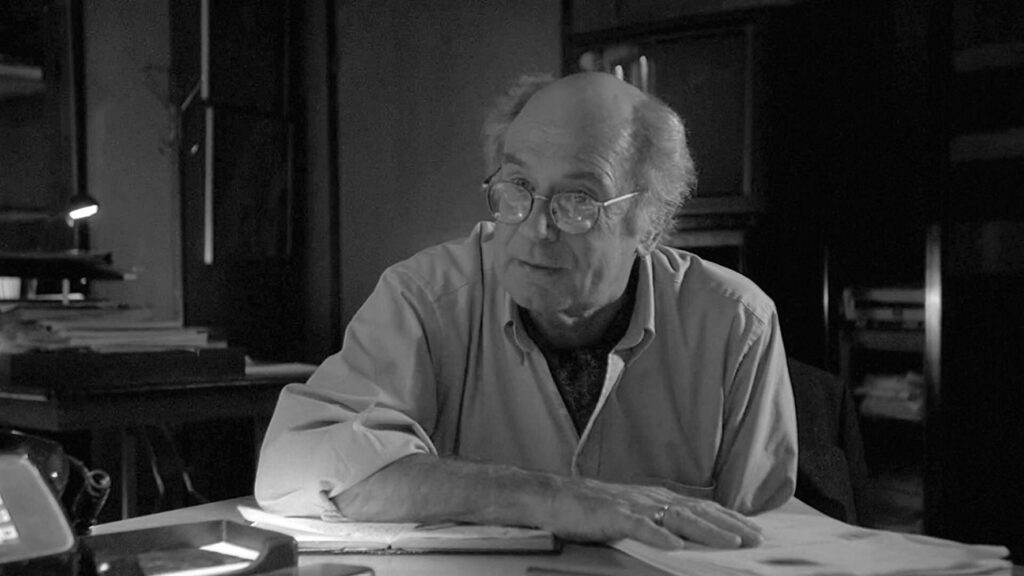

CHARLES NELSON REILLY: January 13, 1931 – May 25, 2007

I’ve always been fascinated by natural talent, particularly iconoclastic natural talent. People who broke down walls of an art form with (seemingly) little to no knowledge of the rules. The Sex Pistols creating punk rock with no musical training. Picasso creating cubism out of thin air. Orson Welles creating new visual methods of storytelling on his first film. Sam Shepard re-writing theatrical narrative as a 24-year old. From the outside, each of these examples seemed to materialize out of thin air, a unique group that created an entire expanded map of the universe without knowing the landscape prior to their journey. Historical examination of these iconoclasts, however, shows that none of them succeeded without knowledge of their creative landscape or without influence. Their groundbreaking creations were actually the result of numerous, less-well-known influences which they then re-arranged to create something utterly unique. Yet, generally, we prefer the idea of “natural born iconoclasm” over study and influence. And that love provides easy opportunity for those who follow in the footsteps of the iconoclasts. Yet, there are groups for whom artistic innovation is a process of intense study. Only by learning all of the rules and knowing where all of the barriers are placed can they decide which walls to knock down. And how. And why. Charles Nelson Reilly – yes, the Match Game guy – was one of the better examples of that kind of artist.

Growing up in the Bronx in the 1930’s, Charles Nelson Reilly was the son of a racist, anti-Semitic mother who would regularly grab a baseball bat and give chase to the neighborhood kids who were picking on her young son for his lack of athleticism and his prominent lisp. His father was a henpecked poster illustrator and painter – talented, but prone to bouts of depression and self-doubt. His lobotomized aunt lived with the family. As Reilly would say in his one-man show, “Eugene O’Neill would not come near my family.” Like many non-athletic, non-violent kids in New York City of that era, Reilly escaped into radio and the movies. He dreamed of someday acting on stage. But dreams were in short supply in his household. (Having survived the Hartford circus fire of 1944 which killed 160 people in the audience, he was left too traumatized to attend the theater as a member of the audience, despite wanting a career on stage.) When an artist from Kansas City was looking for partners for a new venture he would be taking to California, he came to New York to speak with Reilly’s father. He was amazed by Reilly’s father’s work on movie posters, and the man believed the elder Reilly could help him create amazing work in California. He swore the work Reilly’s father would do would be important art work, and his father would be a prominent partner in the new enterprise. Intrigued, the elder Reilly brought the proposal to his volatile wife. “You’re a dreamer!’ she declared, shaming him with the folly of his dreams, reminding him that he was far less talented than he thought he was, and she refused to allow him to destroy their family with his foolishness.

The artist from Kansas City? Walt Disney. Heading out to California to start Walt Disney Studios.

The stupidity of his decision became clear very quickly, and the impotence that the elder Reilly felt about his own life became too much for his to bear. He turned to alcohol, had a massive nervous breakdown, and was institutionalized on and off for the rest of his life. Mrs. Reilly and Charles were forced to leave the Bronx and move in with his mother’s family in Connecticut, where Charles dreamed of returning to New York to learn how to be an actor. His father’s disintegration had resolved something within Charles. Dreams were not something to be ignored or avoided; they were the things that gave our lives meaning and direction. Dreams were our intuition’s way of telling us where to place our goals and where focus our efforts, and Charles decided that no amount of badgering from his mother would stop him from achieving his dream of acting for a living. And so when he graduated from high school, Charles returned to New York, literally and figuratively hungry, and began studying with the legendary theater coach Uta Hagen. Hagen was teaching at HB studios, and – not yet the legend she would become – her policy on allowing actors to join was far more liberal than it would eventually become. Struggling artists who could not afford coaching otherwise were allowed to attend if they showed some promise, and so it was that Reilly attended his first classes with fellow unknowns: Steve McQueen, Jason Robards, Gene Hackman, Hal Holbrook, and Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara. It was here that Reilly got down to the business of studying the craft of acting. Reilly described the state of the class as, “We wanted to go on the stage. None of us had any money, and this entire list? Couldn’t act for shit.”

But Reilly continued to learn the craft of acting, and earned a spot on Broadway fairly quickly. Television was rapidly gaining popularity, and New York stage actors were in demand for the medium. A friend arranged a meeting for Charles to interview with a powerful NBC executive. When Charles entered the executive’s office, he introduced himself, and the executive responded with “We don’t put queers on television.” End of meeting. To most people, that would be the kind of final blow to our resilience. It can’t be easy to hear from an executive in one of the three networks that your sexuality was obvious with only a cursory introduction, and that you were clearly unwanted within an entire medium. Plenty of people would have walked away from that meeting and given up any thought of acting on TV. But not Charles Nelson Reilly. Determined to follow his dreams, Reilly became a fixture on Broadway. He earned a small role in Bye Bye Birdie, but also served as Dick Van Dyke’s understudy for one of the lead roles. This led to an uncredited role in Elia Kazan’s brilliant film A Face In The Crowd in 1960, which led to a role in the original Broadway casts of Hello, Dolly! and a Tony Award for his work in How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying.

By the early 60s, Charles Nelson Reilly was in a position to test the boundary that said that there could be no “queers on television”. His Broadway work made him an ideal candidate for panel game shows like What’s My Line? and talk shows like The Steve Lawrence Show and later on The Tonight Show. Commercial work was also plentiful in New York, and he found himself doing many commercials that were funny enough to leave a lasting impression on audiences. By the late end of the 1960s, Broadway castmates who had made a name for themselves on television were asking for him to guest-star. Children’s television producers recognized both the humor and unique qualities of Reilly’s mannerisms, and they began requesting him for roles in shows like Uncle Croc’s Block and Lidsville. By the mid-1970s, Reilly once counted the number of appearances he was scheduled to make that week in TV Guide – more than 100. Almost fifteen years before, he was told he would never be on television; now Reilly wondered “who I have to screw to get off television?!”

In an episode of Saturday Night Live in the 1990s, actor Alec Baldwin impersonated Charles Nelson Reilly, being interviewed by James Lipton of Inside The Actor’s Studio. The impersonation was spot-on, but the irony of the situation could not be more striking. When asked about his contributions to theater, Baldwin-as-Reilly would point to game shows and affectations with speech and Reilly’s large, square glasses. This was no satire; it was mockery. The punchline of the bit was that the idea of asking Charles Nelson Reilly about his contributions to acting was like asking a birthday cake about its contributions to health and nutrition. It was considered a funny bit, but only to those who don’t know Reilly’s history. For Alec Baldwin – himself no stranger to a limited acting range – to mock Reilly was ridiculous. Baldwin has always been ridiculously handsome. Even older, heavier, and graying, the camera still loves him. The only impediment to Alec Baldwin’s career has been Alec Baldwin. And while Charles Nelson Reilly’s sexuality and mannerisms were certainly part of who he was, and stood between him and success, Charles Nelson Reilly assessed the boundaries and then slowly, patiently, and wisely broke through them. The circle of Alec Baldwin’s influence continues to shrink with each year because, despite being handed life on a silver platter, he continues to throw it on the ground in disgust.

Natural talent appears on the art scene and tears down long-standing walls. As fans of the arts, we watch the changes and marvel at them. But when those changes are a slow evolution, we often miss the power of the change. Charles Nelson Reilly was told he could never be seen on television in the early 1960s. A decade later, he was everywhere on television. Perhaps it was the changing of the times, but more than anything it was Reilly’s tireless work. It’s not merely a lesson in embracing diversity, it’s a lesson in human tenacity. Being told of a significant and immovable barrier, Charles Nelson got to work chipping away at it. Not only because the barrier was unjust (which it was), but because the barrier stood between Reilly and his dreams. And all of us – Reilly, his father, Alec Baldwin, all of of us – have been in that situation. But how many can admit that our reaction was to continue to working until the barrier eroded? To continue to work against the grain for years until that barrier finally gave way? It’s a unique gift that few artists have. And few of them were as fearless as Charles Nelson Reilly.